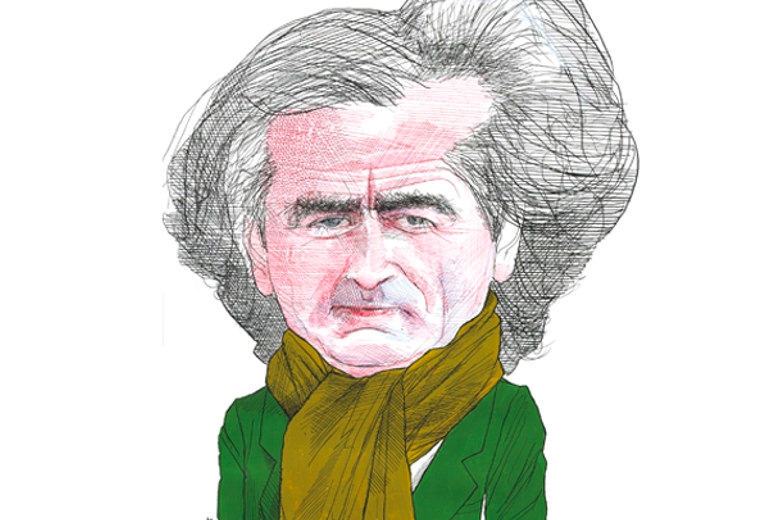

Bernard-Henri Lévy is a haunted man. The French philosopher, speaking to me from Paris, told me that when he was 20 years old, in 1968, a flu pandemic broke out across the world which killed an estimated one million people. ‘It was at least as serious as the pandemic of today but without the same reaction.’

He sees our response to the coronavirus in two ways, positive and negative. ‘It is good news that our respect for life has increased and that we want to save life first of all.’ He calls this ‘undeniable progress for civilization. And for that we have to be really happy’.

But the downside is ‘the overreaction, the sort of collective hysteria which surrounds this phenomenon.’ The first impact has been on the coverage of geopolitics. ‘Big events are being completely deleted from our mental screens. I don’t know what is happening in Syria or to the Christians of Nigeria. The destruction of Idlib concerns me as much today [as before]. But I feel a little lonely on that. All these terrible tragedies have disappeared from our screens.’

He fears that European values are in retreat and that China will use the crisis to push its national agenda. ‘A plan to become Power Number One.’ This fear crystallizes into an aphorism: ‘When the democrats don’t care, the despots care.’

He believes that interest groups want to trick us into imagining that the virus is a political agent with a manifesto. ‘As if the virus had an intention, as if it was helping to create a new society.’

He finds evidence for these sophistries across the entire political spectrum. ‘I hear some ultra-right Americans who says, “the virus is an emissary of God sent to put society in order”’. And the Greens and the anti-globalists are equally guilty of suggesting that the virus was ‘sent by a secular god’ to further their interests.

To him this rhetoric is ‘stupid, disgusting and dangerous.’ Why stupid? ‘A virus does not calculate. There is no intelligence in a virus. There is nothing more blind than a virus.’

Why disgusting? ‘Because this way of moralizing a tragedy is disgusting. I see all these forces trying to take advantage of the pandemic, trying to push their agenda, to say that this pandemic proves something. This makes me afraid.’

He’s concerned that the medical profession has been sanctified without its consent. ‘We should let the doctors and the nurses do what they do, which is to fight the virus with great heroism, without putting on their shoulders a spirit of history which they don’t want. And those who are ill don’t need that too.’

But he’s more worried that the state will use the virus to increase its powers of surveillance. ‘We all know that tracking us by apps, if it happens, should be done with a lot of care because that is very dangerous.’

***

Get three months’ free access to The Spectator USA website —

then just $3.99/month. Subscribe here

***

He hopes that when the crisis is over the French convention of hand-shaking, currently taboo, will be re-instated. ‘It was a habit not invented by but popularized by the French Revolution. It was a democratic habit, a sign of brotherhood, a way to link to each other.’

And he’s concerned that some individuals in self-isolation are starting to believe that their focus on their own egos might be positive. He parodies their outlook: ‘I re centre myself on myself. On the essential. I have forgotten myself.’

He rejects this. ‘Ethics does not mean self-concern. Self-focusing. Self values. No. Ethics begins with the concern for the other. Morality begins when you open yourself to other selves.’

If he has any optimism it comes from the knowledge that viruses also die out. He cites the sweating sickness, sudor anglicus, that spread across Tudor England in the 16th century and expired naturally without scientific intervention. ‘I have never forgotten that a pandemic is a part of human history, it is part of the tragedy of human history. This is nothing new.’

He ended our conversation on a note of stoicism, tinged with anger. ‘Those who have died — 17,000 in France, 13,000 in England — in each and every case a human tragedy. But hands off those guys or ladies who try to invest these sufferings with their political and ideological bullshit.’

Bernard-Henri Lévy will be in conversation tonight with Bryan Appleyard. To purchase a ticket for the webinar, click here. All proceeds for this Hexagon Society event will be donated to the National Emergencies Trust to help coronavirus victims. This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.