It’s been 20 years since the outbreak of the al-Aqsa Intifada, a period of carnage that saw the deaths of over 1,000 Israelis and 3,000 Palestinians. The Intifada killed people and it killed hope. It killed Israeli hopes for an end to conflict and Palestinian hopes to become citizens in their own sovereign state.

In August 2000, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict seemed to be only a couple of signatures away from becoming a footnote in the history of the Middle East. The accepted logic in Washington DC and foreign policy think tanks throughout the Western world was that Israeli-Palestinian peace was the gateway to wider peace in the Middle East. History has not been kind to this assumption. The Syrian civil war and the Arab Spring, during which Israel was an oasis of relative calm and stability, as well as with the recent peace treaties between Israel and the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain — signed without a resolution between the Israelis and the Palestinians — show the error of such thinking.

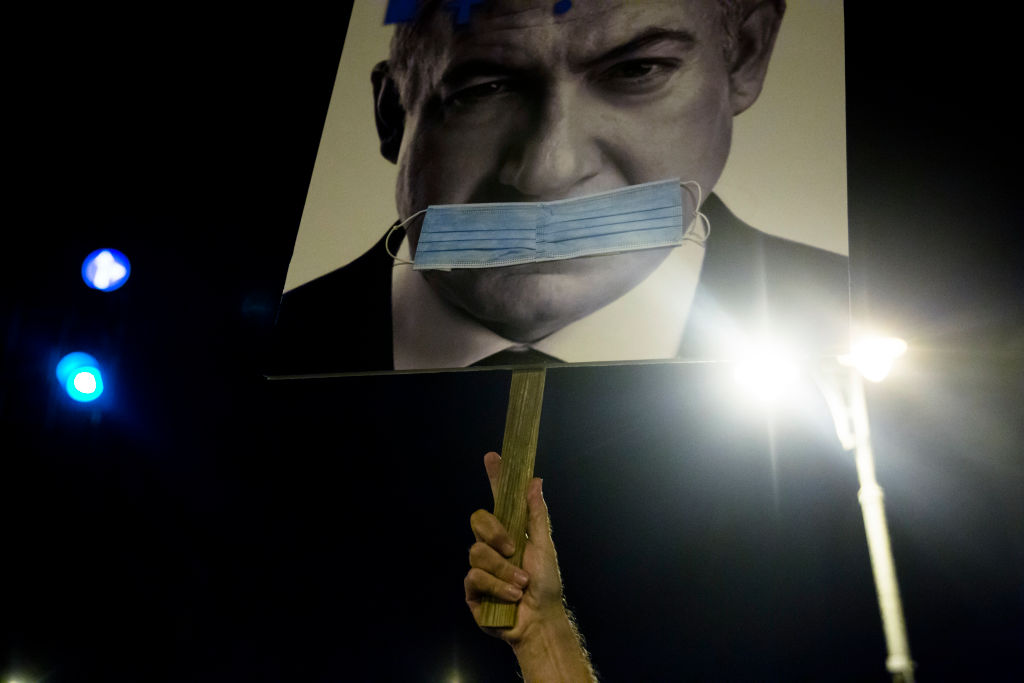

Two decades on, it’s clear why Benjamin Netanyahu is consistently chosen to be Israel’s prime minister by the Israeli public. The devastation unleashed on Israel during the five years of the al-Aqsa Intifada ensured that Israelis just don’t trust anyone else to look out for their interests and see the prospect of a Palestinian state as something to be feared. The constant rocket attacks emanating from Gaza stand as a warning to what Israel might end up experiencing from the West Bank in the wake of an Israeli withdrawal.

I moved to Israel in 2001, a year that saw 30 suicide bombings in a campaign that peaked in 2002 with 55. Suicide bombings went on to account for just over half of the Israelis killed during the Intifada. Israelis won’t forget the sight of buses blowing up on the streets, or the fear of running from restaurants that have just exploded. It helps explain why the electorate have rejected left-wing political parties ever since. What has remained with me from that time is the shock of moving from growing up during the 1990s with the certainty that peace was just around the corner to the horrors of watching that peace explode in all our faces. That shock has never really healed, but as I watch Israel sign peace treaties with the UAE and Bahrain, I can’t be in any doubt that Netanyahu’s own iron wall strategy has paid clear dividends.

In their own way, Palestinian suicide bombings became a metaphor for the self-destruction of the Palestinian cause. Each bombing brought Israeli soldiers such as myself into Palestinian homes and forced diplomats sympathetic to the Palestinian cause to run for cover. Each bombing killed the Israeli peace movement a little more.

Palestine’s president, Mahmoud Abbas, shows the same mentality today as his predecessor Yasser Arafat did in 2000. In a move that has barely registered among Israelis, he has refused to accept the taxes that Israel collects on his behalf. This means that while Israelis bask in the glory of peace with the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, Abbas is unable to pay his own municipal workers. While Israel wins, Palestinians lose due to yet another own goal.

[special_offer]

The Israeli left is still paying the price of the failed Oslo Agreements and the ensuing intifada. The Israeli Labour party has crashed in popularity from winning the 1999 Israeli elections at the head of a 21-seat coalition party to winning a mere seven seats in Israel’s current parliament. At no point since 1999 has the Israeli left been popular enough to become the ruling party. In the election of 1999, when peace was on the horizon, the right-wing Likud won 17 seats; earlier this year, the Likud under Netanyahu won 36, the most successful Likud result since Ariel Sharon won 38 seats in 2002 at the height of the intifada. Israelis simply will not trust their future to anyone on the left.

The lesson of the Intifada for Israelis has been to give up on the idea of living in peace next to a state of Palestine. Withdrawal from South Lebanon and the Gaza Strip saw enemies committed to Israel’s destruction gain a space in which to arm, train and prepare for the next round of fighting, a result that has left Israelis questioning whether it was worth withdrawing from Gaza at all. Gaza looms large as an example of what a Palestinian state in the West Bank might look like should the IDF withdraw. Israelis won’t risk a larger and more populous territory becoming another haven for a terror group sworn to their destruction. Until a credible alternative to that scenario is presented, Israelis won’t change their minds or their voting patterns.

This leaves the Palestinians facing a choice: reach out to the Israelis with their own plan for statehood or embrace the reality of occupation as one that they will be living indefinitely. In the meantime, the Israelis will be voting for Netanyahu and his right-wing Likud who are likely to be securing more peace deals with their Arab neighbors.

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.