My partner and I have just returned from the most magical trip. As guests of Western Australia’s tourist board we’ve driven almost 1,500 miles across the top left-hand corner of the Australian continent. This is the north-west: a landscape like nowhere else on the planet. Three times the size of England, they call it the Kimberley.

I had expected to find Aboriginal people living in these landscapes. They used to, for 60,000 years

Starting from a town called Broome (easy to fly there) we made it overland to Darwin in the Northern Territory. We took about ten days in an all-singing, all-dancing Toyota camper van, sometimes sleeping under the stars, more often staying in comfortable chalets at a string of cattle stations turned campsites dotted along our route. Everywhere was clean and comfortable, everyone was welcoming, the steaks and swimming creeks were bliss, and I’d enthusiastically recommend this adventure — the “Gibb River Road,” they call it — to couples or families keen to get off the beaten track and into the bush, but without any danger, and always within reach of creature comforts. Many Australians do it.

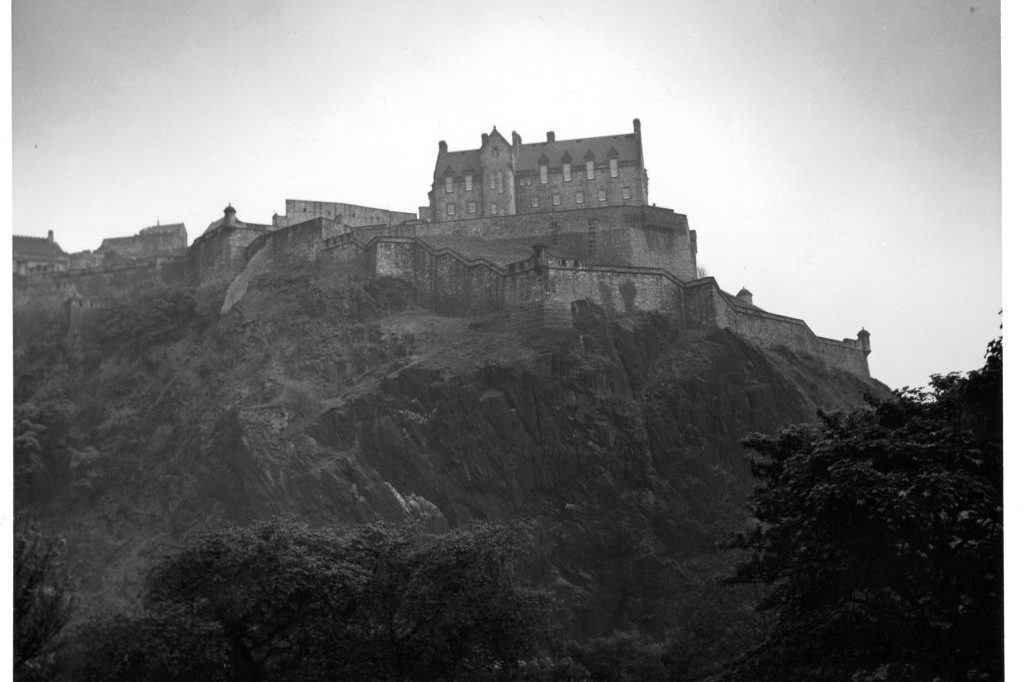

I am writing at length for the Times of London about my experience in Australia. Suffice it to say here that if Walt Disney had created a giant asteroid as a strange yet beautiful combination of hot red earth, orange rock, cliff, mountain and semi-desert plateau, yet cut with ravines, gorges and mini-canyons packed with palm-fringed greenery where clear, cool water tumbles over waterfalls into deep lagoons… they’d still struggle to match the Kimberley.

Within the surprise, though, there were surprises, and it’s one of these I want to write about here. I had expected to find Aboriginal people living in these wild landscapes. They used to, for more than 60,000 years, and everywhere there are rock paintings testifying to the human population for whom this land of miracles was home. They were there when the white people arrived.

They are not there now. Or, rather, they have left the bush, and are living around the very few settlements you could call urban: Broome, Derby, Kununurra. Their art and artistry survives — we visited an engaging workshop and gallery in Kununurra and were hospitably received there — but their situation as a people struck me as marginal, troubled and a little sad. Alcohol is a problem, but the root cause was… oh, I don’t know, but words like “damaged,” “unmotivated,” “beached” spring to mind. One sensed that both sides of the Aboriginal-settler divide feel unsettled about what has happened. I used to think the country’s national “sorry” day, and stuff like that, was all just hypocritical nonsense, but now I’m not so sure.

One evening in Kununurra we were bystanders to an argument — conducted cordially — between a young white Australian and an older retired white lady from Melbourne. The young woman stayed polite but rejected the older woman’s attitude, which was that Aboriginal people won’t take advantage of opportunities offered, leave their garbage lying around everywhere, and in groups feel threatening to people like her. The younger woman was insistent that this lady’s response reflected only her misunderstanding; she had not worked with or got to know Aboriginal people. They did not fit her stereotypes.

We took no sides. The others around the table (mostly retired white Australians) kept their counsel, but I felt that the rather plucky young woman and the equally sincere elderly lady represented two sides of what’s really the same national response to the plight of the Aboriginal people: distress, bafflement and perhaps shame. This emerges differently in different white Australians: on the one side in an angry insistence that the Aboriginal people’s plight is “their own fault;” and on the other a good-hearted but sometimes patronizing insistence that they couldn’t help what has befallen them and the responsibility to repair the relationship lies with white Australia. I’m not sure these two sides are as far apart as their respective protagonists may believe. In both cases despair is not far beneath the surface. Nor is guilt.

What had provoked this argument is provoking similar arguments all across the Australian continent. Someone had mentioned the Voice. This refers to a nationwide referendum to be held in three weeks’ time: on “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.” Australia’s Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s proposal is to set up a federal advisory body to comprise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people representing Indigenous communities. Its role would only be consultative. How the body will be composed and how its members chosen, and how and to whom conclusions would be presented, would be fleshed out later: the referendum really just requests a permission to proceed.

The idea is not uncontested even within Aboriginal communities, and national polling suggests opinion has swung against it. In Australia I saw only Yes posters in residents’ windows, but one has the gnawing suspicion that no poster often means No. As a majority Yes is required not only nationally but in a majority of the states, it appears unlikely to pass. It could fail quite dramatically.

Whichever side you are on, that will be a sad day. It will look to many like a rejection of the Aboriginal people themselves. Watch some of the Yes campaign’s “History is Calling” videos on YouTube. Their message is moving, but implicit in it is that if you care about and respect the Aboriginal peoples, you vote Yes. The lurking corollary — that to vote No is not to care about or respect them — will strike a sour note if No wins, and it’s not what many No voters will have meant to say.

Mr. Albanese looks like setting back the cause his referendum was called to advance. He will leave all sides feeling more raw than when he took it up. Though conceived with good intentions, this has been a serious error of judgment; and, were I Australian, I’d feel angrier about the calling of this referendum than about any possible result.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.