The swimmer Michael Phelps is the most decorated Olympian of all time, with twenty-eight medals, twenty-three of them gold. He is a former world record holder in the 200m freestyle, 100m butterfly, 200m butterfly, 200m individual medley and 400m individual medley.

But let’s just analyze his world-record time for the 200m freestyle — an amazing one minute and 42.96 seconds. Amazing, that is, until you do the math. Over 200 meters I make that 4.34mph. Here’s my problem. I am a fat fifty-eight-year-old man, and I can run faster than that. In boots. In Alabama there are 300-pound, heavily tattooed chain-smokers who can pull a Mack Truck for 200 meters faster than Phelps can swim it.

It’s true that Michael Phelps is an amazing swimmer. But as a form of locomotion, swimming is bullshit

It’s true that Phelps is an amazing swimmer. But as a form of locomotion, swimming is bullshit. You expend a huge amount of energy to attain the kind of speed which sees you overtaken by a toddler on a tricycle. We applaud him for his achievement when we should be deriding him for expending his energies in such a peculiarly inefficient way.

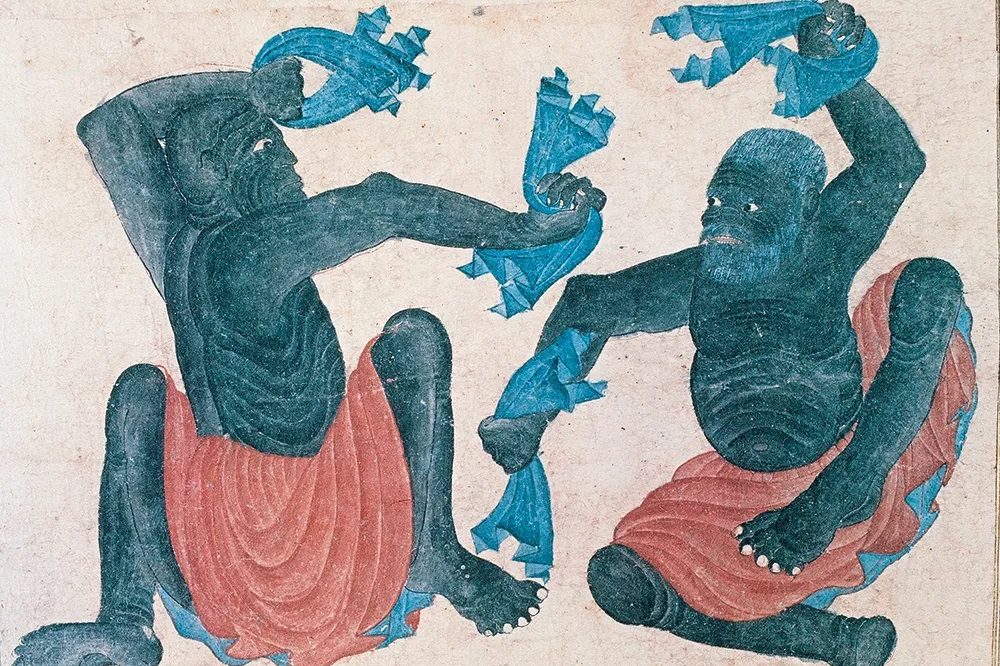

All of which is a roundabout way of saying that effort is not a good proxy for effectiveness. When judging work, we often assume that the hardest-working people are the most productive but, as Olympic swimming shows, this is not always true. Indeed, if Phelps had read his Peter Drucker (“There is nothing so useless as doing efficiently that which should not be done at all”) he might have abandoned swimming for a more energy-efficient mode of propulsion such as the gondola.

And here’s what bothers me. I keep reading articles in the newspapers which read: “It’s time to get back into the office full-time.” And I can’t help wondering whether the authors’ suspicion of remote work partly arises from the fact that it’s less effortful. It’s a kind of Puritan bias. Or, to use the language of behavioral science, “the effort-reward heuristic.” If it’s easier it can’t be as effective.

Yet in the past thirty years we have imposed equally disruptive changes on office workers without remotely equivalent scrutiny. Email, it seems to me, is a massive productivity sink. Typing is vastly slower than speaking; worse still, it is asynchronous. Try arranging a meeting with four other people over a (synchronous) Zoom call and you’ll fix a date in two minutes. Try doing the same thing over email and it will take several days of back-and-forth exchanges. Yet no one really likes email, and it seems to make life harder for everyone, so everyone assumes it is good.

Or consider the open-plan office. I am the vice chairman of a large ad agency. In the 1970s, I would have had an office worthy of Mussolini, with a walk-in humidor and my own personal mixologist. Now I walk into the office and am given a power socket and a chair, and not even the same chair I had the previous day. Again, there is quite a bit of evidence that open-plan offices, like email, stifle productivity, but again no one really likes an open-plan office, and it seems to make life harder for everyone, so everyone assumes it is good.

Now finally, thanks to a pandemic and the internet, we have stumbled on a new mode of working which people actually like. Yet so little faith do we have in people’s ability to use their time wisely, we assume that the mere fact people like it makes it less unproductive. I am far from being a cheerleader for wholly remote work, but we should at least have the sense to be cautiously optimistic. Imagine if we had reacted the same way to the industrial revolution: “Look at that lazy bugger standing in that locomotive pulling levers. We need to bring back the rickshaw!”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply