Easter meant little to me as a child. It was chocolate eggs, magical rabbits, films about Jesus on television. I had three Jewish grandparents and, though not raised with any particular religious identity, there was a sense of cultural Jewishness in the home. But those Easter movies must have made an impact, because I became a Christian in my mid-twenties and am now an Anglican priest.

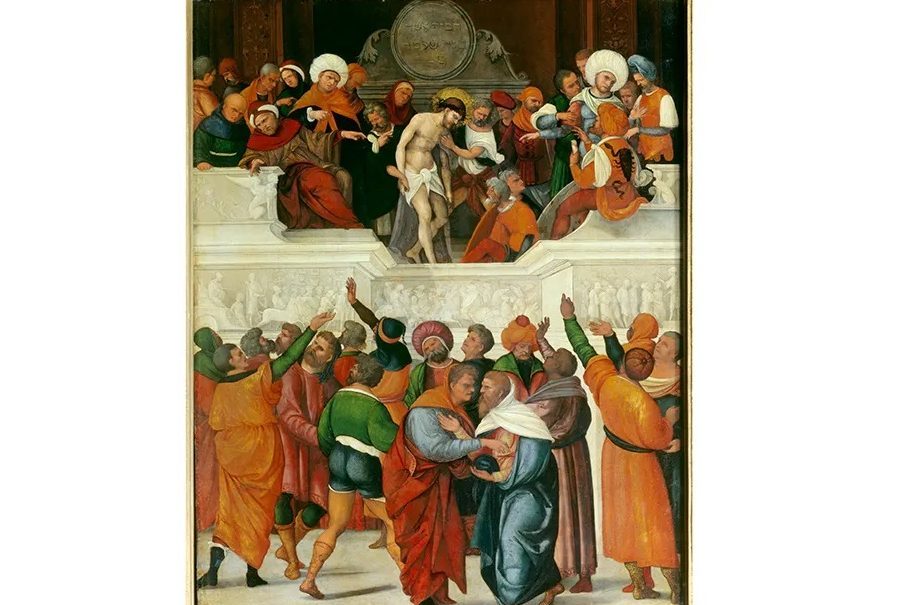

I am, however, deeply aware of Christian antisemitism — something that is once again becoming grimly fashionable. Antisemitism is especially poignant at Easter, the epicenter of the Christian calendar. We remember the great commandment to love one another, and take shelter from an increasingly unforgiving world under the divine promises of Christ personified in the resurrection. Yet it’s also the time when we read of “the Jews” condemning Jesus. The phrase “the Jews” — hoi Ioudaoi in the original Greek — is used more than sixty times in John’s Gospel, and more than two dozen of those references are painfully accusing. It’s difficult to hear of Pontius Pilate saying “Here is your king” to “the Jews,” and them replying: “Away with him! Crucify him!”

John’s is the most troubling of the four Gospels in this regard but Matthew’s Gospel (considered the most Jewish of the canon) has: “When Pilate saw that he was not succeeding at all, but that a riot was breaking out instead, he took water and washed his hands in the sight of the crowd, saying: ‘I am innocent of this man’s blood. Look to it yourselves.’ And the whole people said in reply: ‘His blood be upon us and upon our children.’” Misunderstood and exploited, those lines have caused incalculable harm. I cringe when I listen to some of these texts, though they’re usually read by people who would be appalled to think they were perpetuating anything approaching racism.

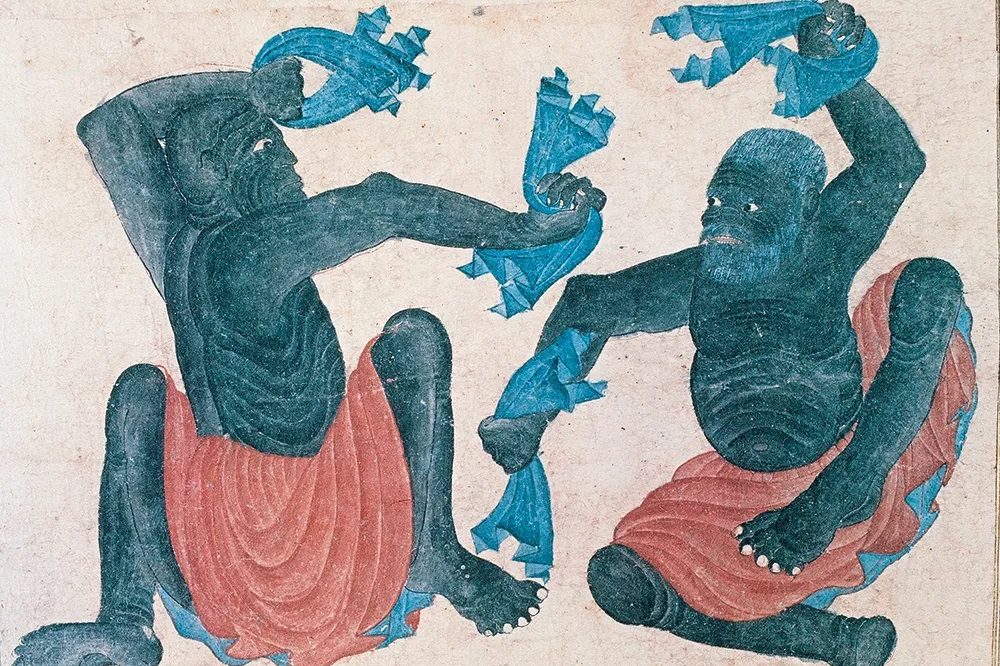

Words are words, but the historical consequences are undeniable. Massacres of Jews often took place during Easter — it used to be a terrifying time. Perhaps the most infamous was the Kishinev pogrom in 1903, in what is now Moldova but was then part of the Russian empire. Mobs of Christians leaving church during Holy Week rioted for two days, murdering forty-nine Jews, injuring a further ninety-two, and committing numerous acts of rape and violence.

Theologians have worked diligently to explain what is going on when it comes to Jews in the Gospels. John was Jewish and his Gospel was written at the end of the first century, when there was direct competition between church and synagogue. He’s not an antisemite, then, but a Jewish believer in Jesus frustrated that his brothers and sisters hadn’t joined him.

In 2010 I attended what is surely the most famous Passion Play in the world, held every ten years in Oberammergau, Bavaria. The subject, the region and the context are all tragically soaked in European antisemitism. But what I witnessed on that cold night, with a thunderstorm above the exposed stage, was the sublime transformation of the Jew as Christ-killer to the Jew as Christ. Indeed, one of the reasons the play is so long is that the contemporary script goes to such pains to emphasize the Jewishness of it all. Jesus is constantly described as a rabbi, the Sanhedrin argue noisily over whether they should accept this new Messiah, and the menorahs are unavoidable. I began to weep, especially when the German actor playing Jesus recited the first line of the Shema — “Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One.” This in Germany, where in living memory genocide spewed its satanic evil on the Jewish people.

Recently in Toronto a fellow priest asked me for some advice. Members of his congregation, none of them Jewish, had asked him if the scriptural passages that were read during Holy Week could be changed to be less insensitive towards the Jews. The priest in question asked me because of my heritage. I was touched. After some consideration, I told him that education and understanding were always preferable to censorship and political tampering. I like to think that the Jewish Jesus would agree with me. His most important message, after all, was forgiveness, since we His persecutors knew not what we did.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazines. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply