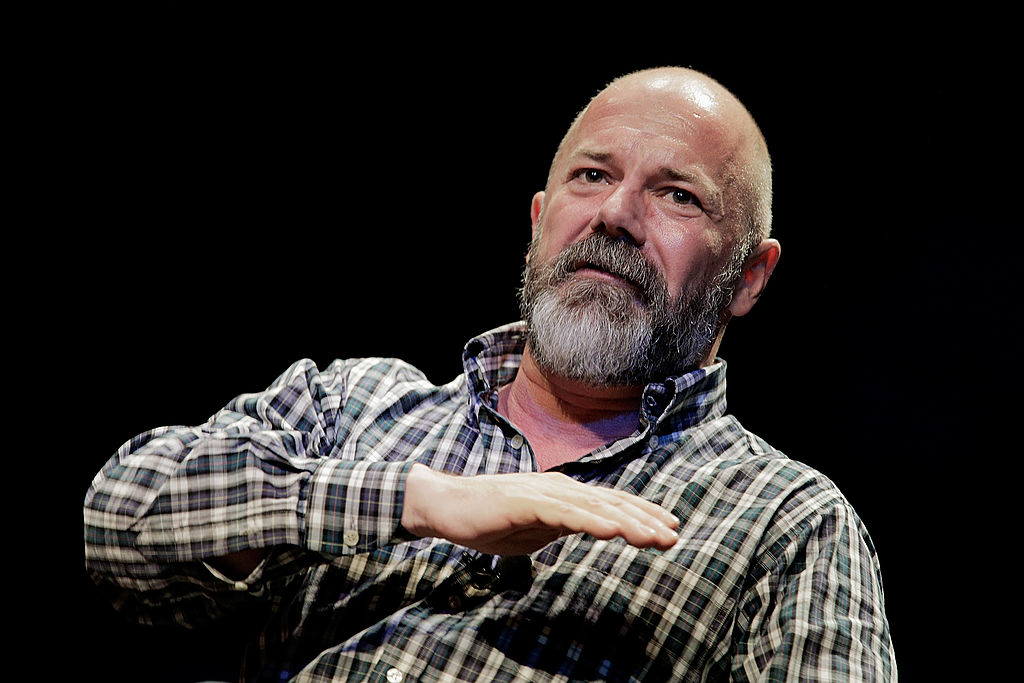

It was daunting preparing to meet Andrew Sullivan, considered one of the cleverest, most fearless journalists of his generation. There is the academic pedigree: the scholarship at Oxford — where he was also president of the union and a celebrated actor — followed by the PhD in political theory at Harvard, where he produced an iconic treatise on the work of British mid-century philosopher Michael Oakeshott, performed the entirety of Hamlet all by himself — “a whacked-out mid-1980s” version — and modeled for Gap.

And there is the journalistic firepower. At twenty-eight, in 1991, Sullivan became the youngest ever editor of the New Republic, America’s most august political magazine. He left following his HIV diagnosis (which he kept private at the time), before beginning the world’s first stratospheric political blog, the Dish, on which he and his team were posting up to forty times a day at its height. The blog was published on TIME, the Atlantic and the Daily Beast before going independent in 2013.

I go to visit Sullivan in New England’s gay capital of Provincetown, right on the tip of Cape Cod, on a blustery October morning. We meet in front of his charming little beach shack, home from early summer to late fall, when he returns to DC. It’s right in the middle of Commercial Street, P-town’s main drag, but set back a bit, hemmed in by flowers, the beach just meters from his porch. He has just been out with his three-legged dog, which he drops off before taking me to his daily breakfast spot, literally one door down. We sit at his usual table, the sea wind rustling the windows impatiently, and he orders his usual: an omelette with pork and cheese, and two moon-like quinoa pancakes, plus bottomless coffee (“it’s how I keep my girlish figure”). Friends appear and recede.

Sullivan has a soft voice and is tranquil and friendly. But the England native’s mixture of preternatural journalistic skill and commitment to what he sees as the truth, however unpopular, has endowed him with the kind of political clout that has led him to the very inner circle of DC politics. By the time of the invasion of Iraq, his support for which he has come to violently regret, he was “close with Cheney, I was close with Rummy [Donald Rumsfeld]” and he is still fast friends with Barack Obama, whose presidential campaign, in an unexpected move for a right-winger, he threw himself behind.

Sullivan denies that he is part of an isolationist turn on the right, but his aversion to robust military responses to threats to the post-war world order is marked. He rejoiced in Biden’s withdrawal from Afghanistan because he believes that real conservatives “don’t believe in transforming the world into a better place through force of arms.” And as Russia pushed Europe to the brink of war, Sullivan was vocal in his support for humoring Putin, tweeting that his requests were “not unreasonable” and that the best way to solve the crisis was to guarantee the limits on NATO demanded by Russia.

And yet, never dogmatic, he has proved more flexible and perceptive than many on the anti-war right, such as Sohrab Ahmari. He wrote a thoughtful piece on his Substack in mid-March that recognized the magnitude of Putin’s wrongdoing and elucidated the idea that as a poster boy for a bombastic, Trump-inflected right, the Russian president has turned out to be a lame and disappointing figure.

Overall, however, Sullivan’s conservatism says that it is wrong for the West to think “you have to prevent a rising power… it does not work, you have to accommodate it.” He applies this to China: “If a power is that great, and a population that large and a civilization that profound, the notion that it cannot have a sphere of influence, that it must be checked at its very sea line when it’s on the other side of the world, is not a sustainable policy.”

Discordant as some of these positions sound to me, Sullivan is first and foremost a political thinker and his views are all underpinned by a serious consideration of ethics and Christian spirit. He remains conservative and Catholic, a politics devoted to the “protection of what is, a love of what is,” a way of thinking that led him to support Republican Ronald Reagan and later Democrat Barack Obama, to loathe Trump, and to be pro-Iraq war and then violently against it. And he has always had a unique knack for weaving together high politics with ideas of sexuality and self. As early as 1989, he made the conservative case for gay marriage, and in 2005, spurred on by America’s misbehavior at Abu Ghraib, he made the case against the use of torture, arguing that using “what is animal in us and deploy[ing] it against what makes us human” was a “totalitarian impulse.”

As the Anglosphere self-immolates on the pyre of identity politics, Sullivan, the iconoclast, the loyalist to the truth, has gone from being a media establishment insider to an outsider, ousted from New York magazine during “the great culling” of 2020 (he’d been a columnist there since 2016). He and the magazine parted ways after his refusal to apologize for a book excerpt of The Bell Curve that he ran in 1994 while editor of the New Republic. The book, by Charles Murray and Richard Hernstein, argued that there are IQ differences between racial groups. Sullivan stands by his decision to publish. In the febrile climate that followed the murder of George Floyd, he was accused of being an accessory to rank racism, but that only deepened his interest in the “psychometric field” of IQ science.

Distilling the balance between cultural and genetic factors will always be hard, Sullivan allows, but “at some point [the idea that not everything is cultural] is not going to be a matter of debate” — even if for now the left “don’t want to accept that this could be true.” But isn’t the fear that research into racial IQ differences could lean towards making scientific Nazism legitimate? “Of course it isn’t… necessarily” going to go there, he says, arguing that there is huge value to knowing what social problems are caused by racism or sexism and which aren’t. Labeling all such inquiries racism is, for the left, simply another “means to excuse not doing things to make things better.”

Whether or not you agree, and I have my doubts, Sullivan is thoughtful, articulate and sticks to his guns. This polite form of iconoclastic free thinking has ensured such an enormous fan base over the years that within four days of his being bumped from New York — the amount of time he was given to pack his proverbial bags — he’d set up a hugely successful Substack, raking in subscriptions to a tune far greater than his New York salary.

Sullivan, who sometimes forgets “how English I am I so many ways,” thinks that Brexit was the perfect conservative response to a populace that felt left behind. Even “leveling up,” he says, is rooted in the “classic Disraeli two-nation idea” of Britain as perilously divided between southern elites and others. Immigration has hit those at the top and bottom of the strata differently.

“There is an anti-immigration argument that’s really built on racism, there’s one that’s laced with xenophobia,” he says, “but there’s also one that’s just wanting to retain something that actually matters, and that gave meanings to people’s lives, and making London cool is not a good social reason to destabilize a whole political culture.”

But Sullivan’s energies lie, at the moment, not in political philosophy but in the epistemological battle to the death between the sane and the ultra-woke, a battle focused, in his view, on the trans debates. Giving in to those who insist that sex is whatever you say it is “makes liberal society much harder to defend. A society that requires you to tell lies is not a liberal society. [We must] stop abusing the English language to avoid reality. That’s what ‘birthing persons’ [instead of ‘mother’] is about.”

A collection of Sullivan’s essays published between 1981 and 2021, called Out On a Limb, came out in August. You wonder, scanning the contents of this book, about the toll taken by a life of such relentless political engagement. Sullivan himself found out in 2015 when he had a breakdown. Forced to step back from the Dish, which he’d kept at continuously for fifteen years, he realized “what the internet had done to me… it was simply the mental exhaustion of absorbing all that information plus formulating it and trying to get it right and doing all that under the glare of constant public scrutiny.” In fact, he describes himself as quiet, with need for solitude. “I have a lot of time by myself,” and instead of the Georgetown dinner parties everyone imagines him to preside over, he prefers to “watch South Park and smoke weed,” and to keep people from normal walks of life around him.

Spirituality looms large for Sullivan, not so much in attendance at mass, which he goes to “sometimes,” but in the sense that “God is everywhere — even on the beach.” Religion has always been there for him personally and politically, but as the world churns with globalization, disenfranchisement and instability, he is increasingly convinced that what it needs more of is Christianity. “I’m increasingly worried that liberal society is actually unsustainable without Christianity and that we may be in serious trouble,” he says. His next book seeks to “reintroduce” Christianity, to “reimagine how we could translate what Jesus was saying to a modern person. I can tell the story of my own faith and in the process wrestle with some of these core challenges of being Christian in the twenty-first century.”

Sullivan assures me that “the book is not just for Christians” and that in casting Christianity aside “we’re [all] missing an astonishing inheritance.” He’s not saying it should be “kept as it always has been,” but rescuing and repurposing Christianity, he says, is a means of finding a “common morality” we have come to sorely lack. Seeing the “individual soul as inviolate is a huge obstacle to totalitarianism, to any form of group identity. It’s the only way that we can live in a very multi-racial, multicultural system and not fall into tribal warfare.”

As a Jew with an angry Old Testament god as my master (well, if I believed), I am not convinced that Christianity will end up being the salve for such a wide range of social and political problems. But I can see that Sullivan is right about a missing dimension in modernity, an emptiness that breeds the urge to escalate and fight in the absence of any other grounding, perhaps even to wage aggressive, amoral and unprovoked wars for nothing more than nihilistic fun.

As my Uber arrives to take me to the tiny Cessna plane to Boston, Sullivan waves me off quietly. His questing spiritualism is a striking counterpoint to much else I encounter, and though it leads him to conclusions many on the right should deplore, particularly the seeming reluctance to take on those who attack the Western order, there is — to mangle Shakespeare — more of heaven and earth in Sullivan’s philosophy than is usually dreamt of, certainly by me.