It is out of sight and usually out of mind, but recent events are forcing Americans to focus on the security of a vast network of undersea cables that the nation depends upon.

In early February 2022, cables connecting Taiwan to its Matsu Islands off the coast of China were cut in what appears to be an act of sabotage that Taipei later ascribed to Chinese vessels. It took nearly two months for the internet to be up and running again, highlighting the importance of a largely ignored element of a country’s critical infrastructure.

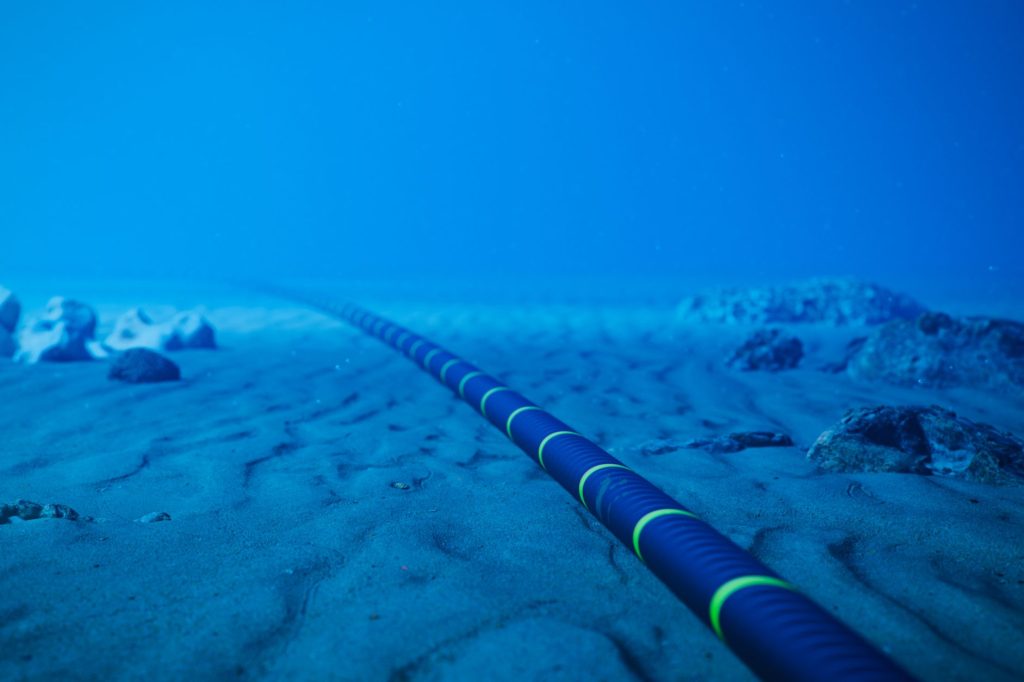

According to TeleGeography, a telecommunications research and consulting firm, there are around 552 undersea cables, connecting almost every inhabited landmass. Most are fiberoptic, utilizing light to transmit massive quantities of data. For perspective, according to the International Submarine Cable Protection Committee (ISCPC), “a single fiber pair [is] now able to carry digitized information (including video) that is equivalent to 150,000,000 simultaneous phone calls.” With numerous pairs per cable and hundreds of cables, the sheer enormity of data is clear; there is simply no other mode of transferring data that can compare — satellites are nowhere close. Brian Cavanaugh, who worked on the National Security Council as senior director for resilience policy in the Trump administration, said that satellites were like putting “a straw on a dam that you just opened — and limiting the water flow to just a straw, where undersea cables permit what you just opened to flow through at real speed.”

The cables carry everything from internet traffic, to phone calls, to pretty much every international financial transaction that occurs on global markets. The American Enterprise Institute’s Elisabeth Braw summed it up nicely when she pointed out that this infrastructure is basically “the entirety of communication and modern life.”

Contrary to what one might expect given their importance, the US government does not own or run the cables American data travels on. Instead, the cable infrastructure is built and managed by private enterprise — though often with government support — and Washington pays for access if it wants to use the cables for government communications. The private sector, therefore, is also where repair capabilities (in the form of cable repair ships) are concentrated. Given that damage and cable outages are far from uncommon — about 100 per year according to TeleGeography — the capacity to service faulty or damaged lines is critically important. While 100 incidents or so per year sounds like a lot, they rarely actually impact anything due to the redundancy built into the system, with numerous cables used and available to transmit data between the same two points.

TeleGeography reports that the vast majority of the damage is caused unintentionally by fishing vessels and other shipping, and about 18 percent has unknown origins. Intentional severance of cables is very rare. Most countries — including China and Russia – rely on the same submarine cables Western countries do, which some cite as a reason why Beijing and Moscow would not attack the lines in the event of a conflict. The argument is that cutting critical lines, say, in the Pacific could cause major problems in both US and Chinese financial systems, so China would not take the risk. Braw disagrees, saying that “you may not care about those consequences for your own country if you are Russia or China, and in fact you may willingly [accept the] consequences because the harm done to the country whose cables you’re disconnecting is much bigger than the harm it would cause you.” Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is Exhibit A. A huge portion of Moscow’s revenue from petroleum exports came from Europe, yet it still chose to invade Ukraine and accept the loss of a massive market.

Proceeding on the assumption that America’s adversaries are willing to accept significant damage in return for achieving their strategic ends, it’s worth considering the threat that undersea cable infrastructure actually faces from state actors. One analyst pointed out to me that just about any oceangoing country can sever cables — indeed, anyone with a large enough ship can do it just by dragging their anchor along the seafloor. That, of course, makes attributing intent difficult — but not completely impossible. “What takes away the appearance of it being incidental,” said Cavanaugh, “is when multiple lines in multiple oceans or multiple landing points are targeted, which takes a sophisticated understanding of who’s in those cable runs.” When several cables are hit in close succession, coincidence can be ruled out with relative confidence — and if it is during a time of hostilities, it will be relatively clear who is to blame.

In the event of a conflict, it’s likely that an attack on cable infrastructure would be more broad-based (and thus more easily attributable), because redundancy makes taking out one or two cables effectively useless for the aggressor. What would motivate countries to cut the cables? Primarily, it would be the impact on domestic life — much of which would be severely impaired if the cable system was compromised — and some important government communications. That presents an opportunity to the aggressor.

Consider a potential scenario in the lead-up to a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. China (and Russia) has the capacity to cut submarine cables beyond the shallow waters where anchors could do the same. The deeper the damage done, the harder it is and the longer it takes to do the necessary repairs. If China were to, for example, cut most of the Pacific cable lines in deeper waters, it would take months to repair them and extensive resources just to protect the repair assets. Any damage and chaos, then, may not be easily remediable. America’s adversaries are also likely to take a targeted approach, trying to figure out what cables “the financial sector is using, to hold the US financial sector hostage, or the US energy sector hostage,” Cavanaugh said, “They will target specific sectors that they think will create more rapid disruption.” Put this all together, and a lot of mayhem could be created right when America needs to get its forces prepared and out of port to defend Taiwan.

There is also a real threat in the realm of gray zone activities. Submarine cables are prime territory for such hostile behavior because “identifying who did it will always be a challenge,” said Cavanaugh, “If you are targeting a specific line, it is easy to mask as an accident.” Hitting one or two cables might not even cause much of a problem on the user end, but it would tie up the limited number (there are about sixty) of repair ships, which are not necessarily going to go where the US government needs them most. “We could have many countries needing a repair ship at the same time,” said Braw, “and other customers already waiting for these repair ships”.

The concern over repair ship availability has led some to advocate for the US getting its own ship(s) so it does not have to rely on the private sector. “We can’t depend on luck or the repair ship owner taking pity on a country,” argued Braw. “So absolutely, we need at least one nationally-owned repair ship for every country.” In contrast, Cavanaugh argues that it is better to leave it to the private sector, but for the government to help out. “Everyone thinks the US government needs to have a cable repair fleet,” said Cavanaugh, “but they are private sector cables, so I think we’ve done a good job where we set aside grant programs and loan assistance programs to build that fleet out, but not get to the point where the US government is manning those fleets.” Presumably, if Washington needed a line repaired urgently (such as in the event of a conflict), it could impress a private sector ship into service, making the private fleet just about as good as a government fleet, but less expensive.

So what can the US do to better protect its cable infrastructure? At the moment, there is no easy answer. Braw points out that this is a particularly difficult case, because the cables are — but also nationally critical infrastructure — that the government does not pay for or run, and that are almost entirely outside of US borders. “By definition it is international infrastructure,” said Braw, “so which government should do how much — I think that is where the conversation needs to go.” They are international in more than just location, too — the cables are used by multiple governments, not just the US.

For better or worse, then, there is not a whole lot that can be easily done to secure the cable infrastructure with any degree of surety. The best Washington can do, it seems, is to lean into a strong deterrence strategy that will prevent America’s adversaries from even considering such a drastic act as attacking the lines. Peace through strength, as the ancient saying goes.