Regular readers may recall how fond I am of a mot from the British diplomat, author and art collector Edgar Vincent, the first (and, as it happened, the last) Viscount d’Abernon: “An Englishman’s mind works best when it is almost too late.”

When I first encountered Lord D’Abernon’s saying, I was impressed by its slightly disabused cheerfulness. “Whew,” I thought. “As usual, some impending disaster was neatly avoided at the last moment by the wit and pluck of the doughty Brits.” The drama of the near-escape added to the sweetness of relief. Surely we Yankees — most of whom, until recently, were basically displaced Brits — could also be counted on to display the requisite derring-do at the critical moment.

Could we though? “Almost too late.” That is, “very close to, but not quite.” Is that where we are now? Or is it more a case, like some victims of the Borgias’ art, of having been dosed with some slow-acting poison? There is no antidote, but it may take months for serious symptoms to appear.

Johnny Mercer told us to “ac-cent-tchu-ate the positive.” Doubtless, from the perspective of psychological health, that is good advice. But that affirmative policy — basically, an exhortation to cheerfulness — is not quite the same as optimism, which was Dr. Pangloss’s folly.

As I write, the United States is some $32 trillion in debt. And that inconceivable sum, as pundits are quick to remind us, includes only the federal debt, the money we’ve borrowed or printed in order to continue living beyond our means. It does not include all the money we have promised to pay out in the near future. Those “unfunded liabilities” nudge the total up to something like $150 trillion.

But who’s counting? I think it was the political philosopher James Burnham who observed that where there is no solution, there is no problem. I suppose that can be read in a positive, Alfred E. Neuman sort of way.

But most of us understand that there are plenty of things whose thorny, problematic, unpleasant natures are not neutralized because they have no solution. Burnham’s point — part of it, anyway — was that there is no use in fretting about inevitable evils. If they are truly inevitable, they will come no matter what we do. But that commendably stoic attitude can easily shade into defeatism, something else Johnny Mercer would have cautioned against.

Many historians of the Great War point out how clement and welcoming the summer of 1914 was. Canny observers could see political storm clouds gathering on the horizon, but they seemed to be offset by the merry weather and that sensation of animal complacency that longstanding, unbesieged prosperity encourages.

As I write, Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping, the leaders of Russia and China, have just met in Moscow in a public festival of anti-American good feeling. The Saudis are making nice with Iran, which is eagerly pursuing its program to acquire nuclear weapons.

And speaking of weapons, the United States seems to have given away huge swaths of its own stockpiles. According to one report, as winter ended, more than a million rounds of 155 mm howitzer ammunition, 8,500 Javelin anti-tank missiles, 32,000 anti-tank missiles of other types, 5,200 Excalibur precision 155 mm howitzer rounds and 1,600 Stinger anti-aircraft systems, among many other munitions, had been sent free of charge to Ukraine to aid in its battle against Russia.

This has left the United States with a weapons cupboard whose store is variously described as “uncomfortably low,” “insufficient,” “precarious” and “dangerous.” This is doubtless something that China, looking anew and longingly at Taiwan, has noticed.

On the bright side, the Pentagon has taken steps to assure that American military personnel be addressed by their preferred pronouns and to provide service members a process through which “they may transition gender while serving.” The army may be unprepared to go to war on an actual battlefield, but at least the battle against what Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, called “white rage” is proceeding apace.

An Englishman’s mind may work best when it is almost too late. But as Aristotle pointed out in the Nicomachean Ethics, one can act in such a way that it is no longer possible to choose the right course of action. “When once you have thrown a stone, you cannot just will it to return.”

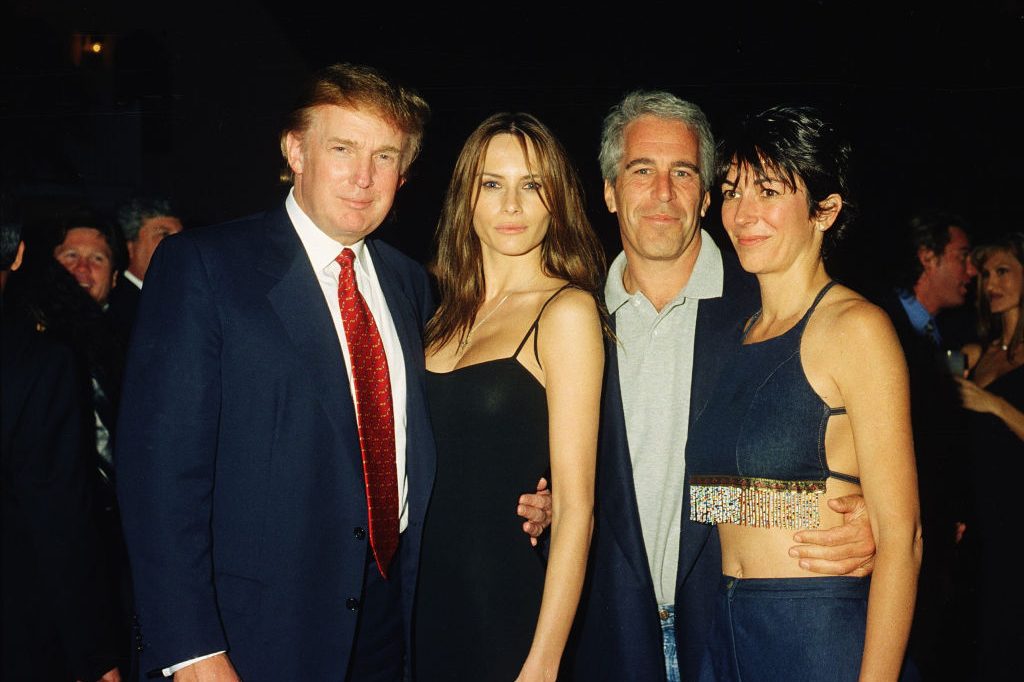

At his rally in Waco, Texas, at the end of March, Donald Trump said that he had recently been asked, “Who’s our biggest threat? Is it China? Is it Russia?” “No,” Trump answered, “our biggest threat are high-level politicians that work in the United States government.” Some people thought that hyperbolic, if not faintly unpatriotic.

I suspect that Trump was right. In 1940, George Orwell put the point with his customary aplomb. “For two hundred years,” Orwell wrote in “Notes on the Way,” “we had sawed and sawed and sawed at the branch we were sitting on. And in the end, much more suddenly than anyone had foreseen, our efforts were rewarded, and down we came. But unfortunately there had been a little mistake. The thing at the bottom was not a bed of roses after all, it was a cesspool full of barbed wire.”

Sometimes, alas, it really is too late.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2023 World edition.