No sensible reader of the news could look at America and think it is flourishing. Massive economic inequality and the breakdown of family formation have eroded the very foundations of society.

Once-beautiful cities and towns around the nation have succumbed to an ugly blight. Cratering rates of childbirth, rising numbers of “deaths of despair,” widespread addictions to pharmaceuticals and electronic distractions testify to the prevalence of a dull ennui and psychic despair. The older generation has betrayed the younger by saddling it with unconscionable levels of debt.

Warnings about both oligarchy and mob rule appear daily on the front pages of newspapers throughout the country, as well as throughout the West. A growing chorus of voices reflects on the likelihood and even desirability of civil war, while others openly call for the imposition of raw power by one class to suppress the political ambitions of its opponent class. Unsurprisingly, the louder the calls for tyranny, the more likely the eruption of a civil war; and the more likely a civil war moves from cold to hot, the more likely it is ultimately resolved through one or another form of tyranny.

What we are witnessing in America is a regime that is exhausted. Liberalism has not only failed, as I argued in my last book, but its dual embrace of economic and social “progress” has generated a particularly virulent form of that ancient divide that pits the “few” against the “many.”

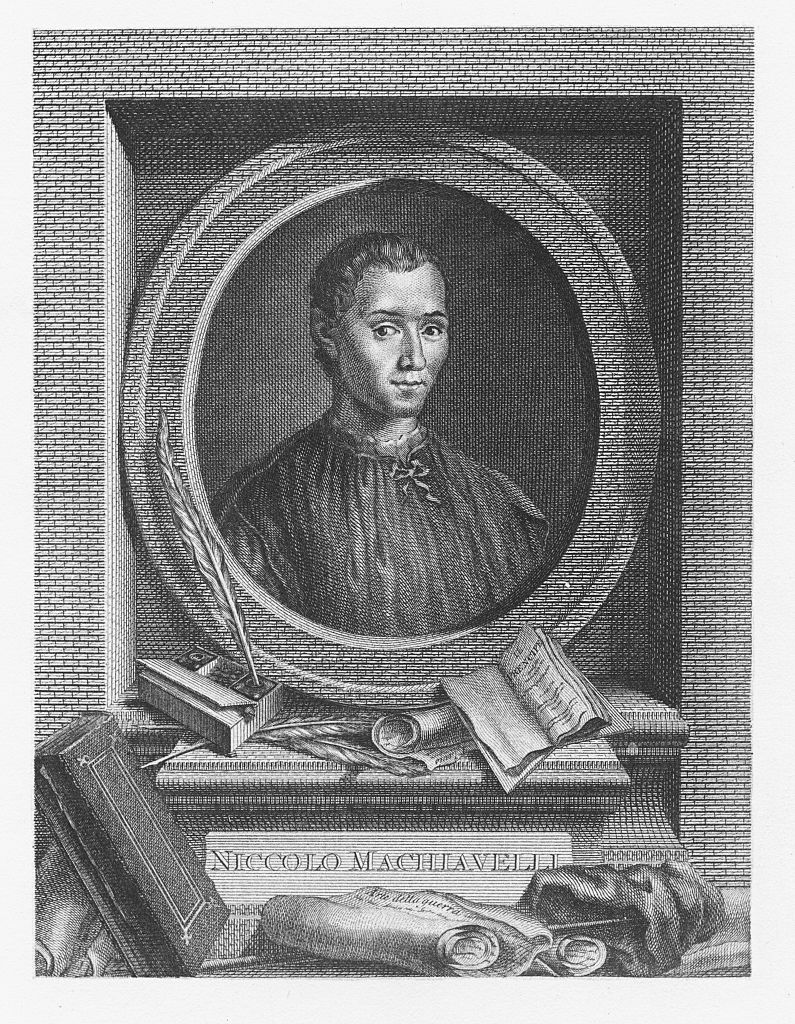

How to reconcile “the few” and “the many” is one of the oldest questions of the Western philosophical tradition. The answer devised by authors as various as Aristotle, Cicero, Polybius, Aquinas, Machiavelli and Alexis de Tocqueville was the idea of the “mixed regime”: a mixing of the two classes. By this telling, the aim was a kind of balance and equilibrium between the two classes, and the good political order was one that achieved a kind of stability and continuity over a long period of time and secured the “common good,” the widespread prospect for human flourishing regardless of one’s class status.

The classical solution was rejected by the architects of liberalism, who believed that this seemingly permanent political divide could be solved by advances in a “new science of politics.” Rather than seeking a “mixed regime,” instead it was believed that a regime governed by a new commitment could overcome the divide: the priority of progress.

The first liberals — “classical liberals” —believed especially that economic progress through an ever-freer and more expansive market could fuel a transformative social and political order in which growing prosperity would always outstrip economic discontents. Far from seeking stability, balance, and order, the aim was what an economy that has fittingly been described as a constant process of “creative destruction.” It was held as an article of faith that the inequality and resulting discontents generated by the new capitalist economic system would be compensated by a “rising tide” of prosperity.

Later liberals — “progressives” — decried the resulting economic inequality, but retained the belief that progress would eventually give rise to the reconciliation of the classes. While they called for greater economic equality, they also demanded dynamism in the social order to displace not now the remnants of the old aristocracy, but the instinctual conservatism of the commoners. This imperative has been especially pursued through transformations wrought in the social sphere, and has in recent years culminated in the sexual revolution and its attendant effort to displace “traditional” forms of marriage, family, and sexual identity based in nature, replaced instead by a social and technological project that would liberate humans from mere nature.

Progressive liberalism has held that through the overcoming of all forms of parochial and traditional belief and practice, ancient divisions and limits could be overcome and instead be replaced by a universalized empathy. With the advance of progress, the old divisions — once based in class, but increasingly defined in the terms of sexual identity — would wither away and give rise to the birth of a new humanity.

Both liberal parties — “classical” and “progressive” — believed that progress was the means of overcoming the ancient division between the classes and how political peace might be realized; but both recognized and feared that such progress would, in each instance, be thwarted by the common people, who would most immediately find the fruits of that progress not to be beneficial, but destabilizing, disorienting, and an affront to their beliefs, practices, and even dignity. The faith that political peace could best and only be achieved through progress required that effective control of the political order be reserved to liberal elites on both the right and the left who would secure the blessings of progress, whether economic or social.

While the two sides of liberalism opposed each other over means, at a deeper level they effectively combined to ensure the prevention of a dedicated “people’s party” which would oppose progressivism in both the economic and social domains. The liberal fear of the demos resulted in a political order that was, at its foundations, dedicated to the rule of more progressive elites over the threatening demos, and, throughout American history, has been impressively effective at preventing the rise of a genuine populist party. The ideal of “mixed regime,” or “mixed constitution” was replaced by the creation of a new and entrenched progress-oriented liberal elite, one that today increasingly views the demos as a threat to its project — whether economically or socially.

During the brief Pax Americana of the post-Cold War world, the liberal West had grown accustomed to a political divide between right and left-liberals, contentious yet manageable political division in which each side of liberalism would be advanced successively in the economic and social spheres through the oscillation of electoral victories. This brief interregnum of “neo-libertarianism” — in both its “conservative” and “progressive” forms — has been shattered by the reappearance of that oldest political division — the division between the “few” and the “many.”

Whether “classical” or “progressive” liberals, their inherent fear and mistrust of the demos was and remains expressed in their panic over the rise of populism. Strenuous efforts are today exerted to prevent a political realignment that would result in a people’s party opposed to the liberal progressive project. On the notional “right” of the liberal spectrum, extremely well-funded efforts ceaselessly attack the “authoritarianism,” anti-expert ignorance, and economic “socialism” of populism; on the progressive liberal “left,” relentless efforts paint every conservative opposition to social and sexual progressivism as racist, bigoted, and fascist. The two liberal oppositions have coalesced in the form of “woke capitalism,” the perfect wedding of the “progressivist” economic right and social left, a combination that aims to produce a populace that is satisfied with diversion, consumption, and hedonism, and, above all, does not disturb the blessings of progress. And, if that doesn’t work, it uses the levers of political and corporate power to suppress populist threats.

Yet these efforts are proving inadequate because the consequences of unfettered progress are no longer acceptable to the demos. The populist backlash around the world is simultaneously against liberalism in both its “right” and “left” forms. It rejects the economic “neo-liberalism” of the post- Cold War American imperium, demanding political and economic boundaries, protection of national industries, greater worker protections, and a more muscular prevention and even dismantling of monopolistic concentrations of economic power. Equally, it pushes back against the social liberalism of progressives, opposing the self-loathing embedded in contemporary approaches to national history, combating the sexualization of children, seeking limits on pornography, rejecting the privatization of religious belief, and even has achieved an overturning in the legal domain of the libertarianism at the heart of America’s half-century abortion regime.

In other words, the liberal “solution” now generates a worsening of the very divide that it claimed to be able to solve through the application of “progress.” While ruling elites strive to double down on an acceleration of economic and social libertarianism, the accumulating negative consequences of the resulting policies have led to the rise of populist commoners opposing both sides of liberalism. The “many” are achieving “class-consciousness” — not as Marxists, but as left-economic and socially conservative populists. If the liberal “solution,” in fact, only worsens the political problem it claims to have solved, then a new approach is demanded.

With the dimming of the bright light of liberalism and its seeming historical inevitability now relegated to the dustbin of bad theories of history, both the need and the prospect for liberalism’s true and natural opponent arises: a movement that begins with, and is defined by, a rejection of the ideological pursuit of progress along with the baleful political, economic, social and psychological costs of that pursuit. This project is one both of recovery and reinvention, plumbing our own tradition for resources capable of addressing our current political impasse, but now articulated in contemporary terms that would be at once novel as well as recognizable to such thinkers as Aristotle, Aquinas and Tocqueville.

What is needed — and what most ordinary people want — is stability, order, continuity and a sense of gratitude for the past and obligation toward the future.

What they want, without knowing the right word for it, is a conservatism that conserves: a form of liberty no longer abstracted from our places and people, but embedded within duties and mutual obligations; formative institutions in which all can and are expected to participate as shared “social utilities”; an elite that respects and supports the basic commitments and condition of the populace; and a populace that in turn renders its ruling class responsive and responsible to protection of the common good.

What is needed, in short, is regime change — the peaceful but vigorous overthrow of a corrupt and corrupting liberal ruling class and the creation of a postliberal order in which existing political forms can remain in place, as long as a fundamentally different ethos informs those institutions and the personnel who populate key offices and positions. While superficially the same political order, the replacement of rule by a progressive elite by a regime ordered to the common good through a “mixed constitution” will constitute genuine regime change.

While the “postliberal order” will cut across current political parties, its current best hope is a “new right.” This label obscures as much as it assists, since a great deal of the economic program of the “new right” takes its cues from the older social democratic tradition of the left. However, today’s left has largely abandoned the central commitment accorded to the working class, viewing its social conservative tendencies as a deeper threat to progress. It has become clear that the right is more willing to “move left” economically than the left is to “move right” on social issues. This tendency is more than merely accidental, but represents a return of conservatism to its original form — a consolidated opposition to liberalism. Any advance of economic equality will be accompanied by a greater effort to foster and support those institutions from which deep forms of solidarity emerge: family, community, church, and nation.

The emergence of a “postliberal” new right is, in effect, a rediscovery of early-modern forms of conservatism, and echoes conservatism’s earliest thinkers, who warned of the dangers emerging from an ideology of progress. These thinkers, in turn, reached back to the ancients to learn anew lessons about the “mixed constitution.” While ancients such as Aristotle, Polybius and Aquinas had no word for “conservatism,” they offered its original articulation: a political and social order of balance, stability and longevity that achieves the common good through forms of political, social, and economic “mixing.” This revival of a core teaching from the very origins of Western political thought might properly be labelled “conservative” if we understand that any undertaking to “conserve” must first more radically overthrow the liberal ideology of progress. For our purposes, I will give this alternative a label that combines its ancient and modern labels: “Common Good Conservatism.”

What’s needed is a positive and hopeful vision of a postliberal future. Change will not occur simply by a mythic revolutionary uprising of the many against the few. Rather, it will require some number of “class traitors” to act on behalf of the broad working class, articulating the actual motives and effects of widespread elite actions. Even if relatively small, an elite cadre skilled at directing and elevating popular resentments, combined with the political power of the many, can bolster populist political prospects as a working governmental and institutional force. In turn, a new elite can be formed, or the old elite reformed, to adopt a wider understanding of what constitutes their own good — a good that is indivisible and common — and to return society to a state of flourishing.

This is an edited extract from Regime Change: Towards a Postliberal Future by Patrick J. Deneen, to be published by Sentinel on July 6, $30 hardcover.