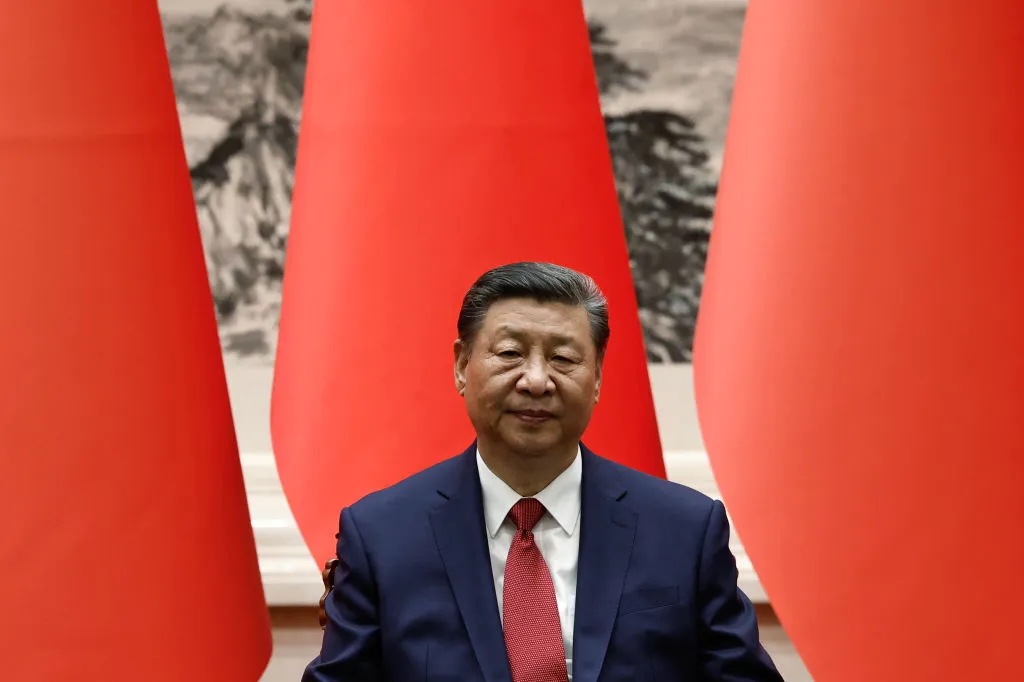

The world may not be turning upside down, but it’s certainly tilting. In the long shadow of the pandemic, with war on the European continent and the West and China entering a new cold war, the “new economy” of bits and bytes that was supposed to connect and shape the world has hit a rough patch. Meanwhile, the much disdained “old” economy of manufacturing, agriculture and energy is thriving.

Today, it’s not steel companies or gas plants that are experiencing mass layoffs, but firms such as Goldman Sachs, Meta, Amazon, Microsoft, Snap and Google. Last year, media companies lost $500 billion in value and tech firms have shed $4 trillion off their valuations. Industrial spaces are in high demand while downtown offices sit half-empty. The fossil fuel giants are enjoying record profits as the beneficiaries of ultra-subsidized renewable schemes, which excited investors with dreams of guaranteed profits, flounder.

The work-from-home revolution was sparked by the pandemic but has endured long after the lockdowns ended, accelerating the decades-long shift away from urban areas. Ten years ago states dominated by big cities, such as New York and California, were riding high, or could at least pretend they were. Today virtually all the rapid growth in population and the biggest growth in new jobs is taking place in redder, lower density states like Texas, Arizona, Tennessee and Florida.

These trends amount to a fundamental geographic shift and suggest the possibility of a transformed political map. The center of American power has moved around the country time and again, starting with the frontier ascendancy over the New England elites led by Andrew Jackson two centuries ago. Lincoln, backed by the Midwest and rapidly industrializing Northeast destroyed the old south while the Roosevelts, representatives of an ascendant New York-led urban politics, shaped the first half of the last century. Later, California’s ascendancy sparked the rise of Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan and, briefly, Jerry Brown.

Now we could be entering a new era, with people and economic power shifting to sunbelt states, some parts of the Heartland and the suburbs almost everywhere. Since 2015 smaller metros and urban areas have been gaining people at a rate far faster than the traditionally dominant big cities. Between 2010 and 2020, suburbs and exurbs accounted for about 80 percent of all US metropolitan growth.

The pandemic intensified these trends. Last year, New York, California and Illinois lost more people to outmigration than any other states. Demographer Wendell Cox notes that the largest percentage loss of residents occurred in big core cities such as New York, Chicago and San Francisco. In contrast, populations grew in sprawling areas such as Phoenix, Dallas and Orlando.

Immigrants, who previously headed to the West Coast, the Northeast and Chicago, are migrating instead to places like Dallas, Miami and even small towns in the Midwest. Los Angeles’s foreign-born population declined over the past decade.

Even before the pandemic, affluent young professionals were heading to less expensive and congested cities in search of homes they could afford. Regulations have made starting or expanding businesses in the deep blue states increasingly difficult. Last year, the biggest upsurge in new business formation took place in the Deep South, Texas and the Desert Southwest while New York and the West Coast economies lagged. According to recent analysis by Zen Business, Texas and Florida are now the country’s high-growth hotspots and are also attracting the most tech workers.

Housing, particularly for young families, is a critical driver. As measured by the Demographia Housing Survey, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle and New York suffer the highest housing costs while prices in much of the country — mostly outside big cities and in red states — remain relatively low. This has led to growing numbers of people moving long distances, notes the National Association of Realtors, mostly to suburban, exurban, small town and rural locales.

The pandemic alone did not create the relative demographic and economic decline in blue America; persistently high crime rates and the rise of remote work have undermined its economic preeminence.

It’s not just where people are moving that is driving this shift, but where they are having children. The states with the highest fertility rates are all deeply red — the Plains States, Utah, Alaska, Louisiana — while the least fecund are ultra-blue jurisdictions like the District of Columbia, Vermont, Oregon, Massachusetts and, remarkably, California. Much the same can be seen among metros; fertility rates are highest in places like Dallas-Fort Worth, Jacksonville, Salt Lake City, which lean to the right, and the lowest in indigo metros like San Francisco, Los Angeles, Boston, San Jose, Washington and New York.

This suggests that the red states, suburbs, and rural areas will continue to obtain a bigger share of the political pie. Since 1990, for example, Texas has gained eight seats in the House of Representatives, Florida five and Arizona three. In contrast New York has lost five, Pennsylvania four and Illinois three. California just lost a congressional seat for the first time. Today the largest bloc of congresspeople come not from cities but “mixed” districts of suburban and rural voters. If the current trends continue, these numbers will likely swell.

***

Compounding all these trends is the strength of the “old” economy, which has turned out to be a windfall for red states. Today it is oil companies, agriculture businesses and some manufacturers who are hiring and growing, enriching large parts of the country, notably the Southeast and, to a lesser extent, the Great Plains. Despite the opposition of progressive policymakers around Joe Biden, businesses are once again seeing the power of the resource economy. One of the biggest projects being built in the country today is a new LNG facility on the Louisiana coast, designed to send gas to Europe; the state is placing big bets on the material economy that still dominates global trade.

At the same time, the red and Sun Belt states are also poaching the very fields that “new economy” regions were supposed to dominate. Over the past five years, finance, business services, business management and even tech jobs have shifted from traditional hubs like New York, LA, Chicago and San Francisco to places like Austin, Dallas, Salt Lake and Raleigh-Durham. In 2021 Texas and Florida spurred more new tech start-ups than California; Dallas-Fort Worth, Miami and Salt Lake City all added more new jobs than Silicon Valley. Over the next decade, according to one survey, Utah, Arizona, Texas, Colorado and Nevada are expected to have the biggest tech growth, well ahead of California, New York or Massachusetts.

These changes will clearly alter our economic geography. In 2022 California suffered among the worst personal income growth rates in the country, and lagged arch-rival Texas in growth by more than two to one. The rich from places such as New York, New Jersey, Illinois and California are on the move too. Blue state governors such as New York’s Kathy Hochul and California’s Gavin Newsom now openly express worries that new tax-the-rich schemes, like proposed wealth taxes, could accelerate this process. Even a progressive posturer like Newsom knows he needs the wealthy — the one percent pay roughly half of his state’s income taxes — and that they can absorb only so much expropriation.

The signs of fiscal distress are already evident. In California, a once huge budget surplus has morphed into the deficit of $25 billion. Ultra-blue New York, Illinois and Massachusetts also face large, and expanding, shortfalls. In contrast, Texas, Tennessee and Florida, as well as a host of Heartland states, all enjoy large surpluses, and are considering considerable tax cuts.

Even tech and green industries demanded by, and often originating in, blue states are headed elsewhere. Industries that originated in the Golden State, like the semiconductor sector, are heading elsewhere, notably to Ohio, Arizona and Texas. Most new electric vehicle and battery plants are located either in the Heartland, the South or other locations east of the Sierra Nevada.

Deep-blue states are suffering the consequences for their single-minded focuses on tech and high-end services. In the future the big demand, notes former California labour commissioner Michael Bernick, will be for people who can drive a truck, construct a house, change beds, service your pipes or perform nursing duties. Yet California, New York and other blue states rank among the worst places for blue-collar workers, who cannot make enough in the state’s high-tax, high-cost environment, and have been headed elsewhere for a generation.

From Ron DeSantis’s rise as head of the “Free State of Florida” to abortion debates and voter concerns over rising violent crime rates in large cities, the geographic dimension of the national politics is already hard to miss. Next year’s election could prove to be an inflection point: a domestic version of Samuel Huntington’s “clash of civilizations.” The election may turn into a referendum on whether to promote the interests of cities and blue states or those of suburbs and regions experiencing dynamic growth. California — the state model for the Biden administration — may not be the preferred template for places such as Texas and Florida that are attracting more investment and migrants

There will also be a distinct class and industry divide. Professions most likely to back the GOP are precisely those that benefit from an industrial, material economy while the better educated “creative class” tilts Democratic.

In this contest, it would be a monumental mistake to underestimate the Democrats and economic incumbents on their side. The center of power may be shifting, but the power of the oligarchs and their allies in the financial and non-profit sectors remains considerable. Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Bezos, Tim Cook and co are not about to be deposed. The Silicon Valley-Puget Sound duopoly continue to dominate virtually all tech sectors. They seem poised to dominate the coming things, such as artificial intelligence, where both Microsoft and Google are is taking the lead, as well as Mark Zuckerberg’s big plans for the metaverse. Despite the occasional populist rhetoric from both parties, there seems little prospect of Washington limiting mergers that allow for ever greater concentration. Big tech may be in the gunsights of both progressive reformers as well as some prominent conservatives but well-funded lobbying may blunt those attacks.

None of this means neo-feudal oligarchs can easily impose their will. Almost all the institutions controlled by progressives — media, Hollywood, universities, the federal bureaucracy, the large corporations — now suffer among the worst levels of trust in modern history. At the same time, their untimely rejection of the material economy hurts many traditional Democrats, including immigrants and minorities, notably Latinos.

In the coming years, progressives will have to work overtime against a changing demographic and economic balance of power. The GOP, by contrast, is well-positioned to capitalize on epoch-shaping changes. But it will require a laser focus on economic issues as well as relieving themselves of both Donald Trump and the extreme cultural conservatism that alienates voters even in places like Texas.

Though it may be early for such predictions, the next election may boil down to whether progressive guile, a likely choreographed Democratic shift to the center on issues like climate combined with relentless GOP stupidity, will prove sufficient to overcome massive structural changes that now, for the first time since the 1980s, favor the right.