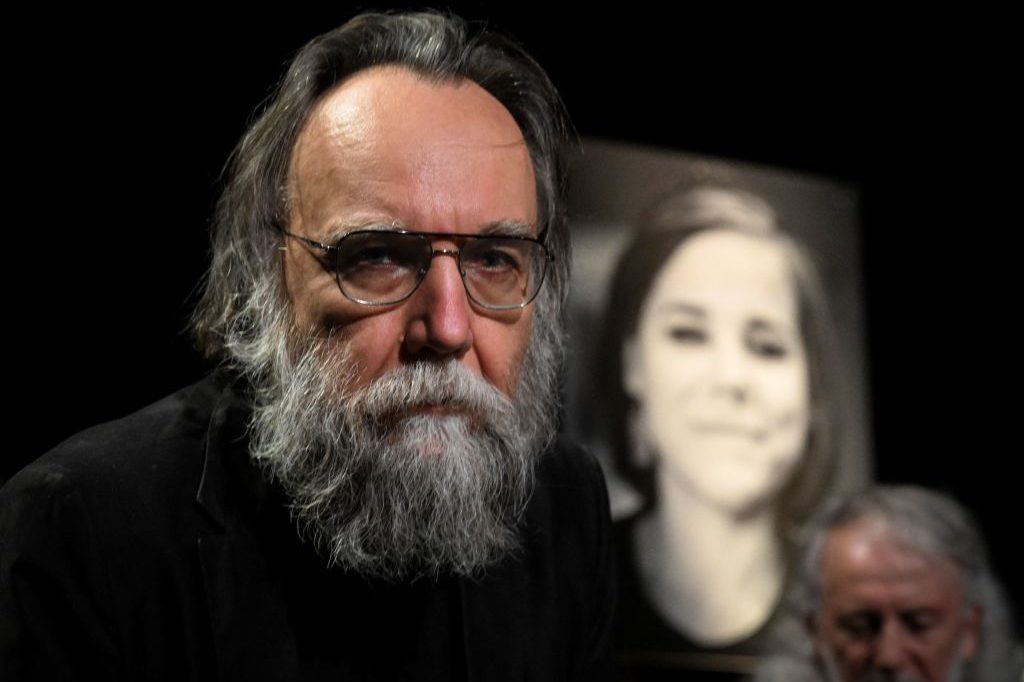

Is the invasion of Ukraine a holy war? If that is how Vladimir Putin sees it, it might have something to do with the ideas of Aleksandr Dugin, a former anti-communist who is touted by some to be the Russian president’s favorite philosopher. He is described as a Rasputin-style mystic, a comparison which is aided by his thick beard.

For him, Ukraine is a proxy war against the “satanism” of the West. While the level of his influence on Putin is disputed, there is no question that this unapologetic supporter of the Ukrainian invasion has had a major impact in Russian intellectual and political circles and has gained a growing audience in China, the Middle East, Latin America and the developing world.

I spoke to Dugin towards the end of last year, shortly after the first anniversary of the assassination of his twenty-nine-year-old daughter Darya, who was killed in a car bomb outside Moscow. While nothing has been proven, Ukrainian elements have been suspected, by western intelligence as well as by Russia. Darya had herself made enemies — she ran a website regarded in the West as spreading propaganda on behalf of the Wagner Group — but many believe that Dugin himself may have been the intended target. He is thought to have changed cars at the last minute.

“It’s personal,” Dugin tells me. “They have killed not only her. They have killed me and my wife. Everything stopped on August 20, 2022. It was a success for Satan and his slaves. And maybe they killed me much more than they could because they killed me a hundred times. So they have achieved their goal. Martyrdom for her and for myself and for my wife, for her mother. So I feel myself crucified with her.”

Dugin’s loss is the backdrop to his vision of the war Russia is fighting. “I don’t consider Ukraine to be just a small regional disagreement,” he says.

It is a major event, perhaps the biggest in history.” Dugin’s big idea, one shared by Putin and many other world leaders, is that the “unipolar” world, dominated by the West, needs to be destroyed in favor of a “multipolar” one, with multiple superpowers. This, he argues, will free nations from the grip of western liberal imperialism and usher in an alternative world order made up of independent civilizations. Russia would be one, China another. Alongside them would be the Islamic world, Africa, Latin America, and the West — though the latter would no longer be dominant.

“The situation in Israel is a part of this global geopolitical puzzle,” he says. “There are two clearly defined camps: unipolarists (the globalists) and multipolarists. Nobody could approve what Hamas did. But from the moment the US and the liberal globalist establishment in the EU and Great Britain sided with Israel, the die was cast. The multipolarists are on the side of the Palestinians. Putin has excellent relations with Israel and with [Benjamin] Netanyahu above all. But the multipolar logic obliges him to support Gaza and blame the IDF.

“More than that, the Islamic pole is forming against the US and the collective West. So the Muslim world population is becoming more and more conscious about the geopolitical structure of the global balance of power. They are beginning to understand better the Russian-Ukraine war (another front of the emerging pole against globalist unipolarity) and the Taiwan case. Everywhere there is only one hermeneutic: globalists against multipolarists.”

The ruling economic and political system in Dugin’s ideal world would be neither capitalism, communism nor fascism, but something which he regards as combining the good elements of all three. Dugin also draws on the ideas of the early twentieth-century British geographer Sir Halford Mackinder, who proposed that history was a battle between land powers and sea powers. Russia, says Dugin, is the former and the West the latter: “Between them there is conflict as between Rome and Carthage, between Athens and Sparta, part of the permanent historical confrontation between two types of civilization.” As for Ukraine, it is part of the “Rimland.” Control of the Rimland, as Dugin and Putin see it, determines the balance of power between the sea and land.

To understand Dugin’s geopolitical ideas you also need to understand his religious philosophy. In his view, Orthodox Russia plays the part of Katechon in Thessalonians — the bulwark against the Antichrist West, or as he puts it the “LGBT+, transgender, transhumanist, postmodernist, relativist, anti-human, totally perverse West.” In Dugin’s view, the West is destroying itself through its liberalism, which has damaged collective identity. He brings up gender politics again and again.

He is also keen to emphasize that Britain is not just the “Little Satan” to America’s “Great Satan”; it is worse, he says. He claims he once had hopes that Brexit might allow Britain “to liberate itself from the globalist European liberal elites,” but this did not happen. Rather it summoned the “phantom pain of a lost empire, the worst aspects of British imperialism, but without the power.” It gets worse. “I think now Great Britain in my opinion is a caricature. It is a small and ugly monster that we really despise, and we have begun to hate the British more than the Americans. The Americans are just stupid, but the British are really evil.” It is a loathing, he believes, which is reciprocated. “In the heart of satanic civilization, the hatred is growing,” he says. “Demonization of Russia, of Putin, and all of us in the multipolar world, is hardening.”

For all his religious fervor, there was a time, Dugin says, when Russia might have accepted a “two-state solution” in Ukraine — with the eastern half becoming Russian and the western half remaining an independent country under western influence. “I consider this impossible after this bloodshed, after the level of hatred and killings and rage on both sides,” he says. “So we are in a situation where either Ukraine will in future cease to exist, and will become part of south and western Russia, or there will be no Russia. No Russia as it is now. The trouble is there is also a third possibility, where there will be nobody. Neither Russia nor Ukraine, nor humanity nor the West.” The nuclear option, in other words.

Dugin explicitly warns that it is folly to ridicule Russia’s reasons for going to war. “Eschatology is present in our minds and influences our decisions,” he says. “You can laugh at it, but you should remember that you laugh at people with nuclear weapons. I see no reason why we should not use them or why Putin will hesitate to use them if Russia starts to fail.”

He is honest about the losses both Russia and Ukraine have incurred. “Ukraine is in ruins now… The reconstruction, rebuilding [and] repairing will take all [of] our efforts… Russia will not immediately be a military, economic giant that could really threaten the West. Russia will have lost so many people. We are isolated from the West. We are cut off. We are in a weak position… the West could easily coexist with us.”

But Russia’s setbacks in Ukraine have failed to diminish the zeal of its cause, even if it has reduced the territorial ambitions. “An absolute majority of Russians support Russia’s existential fight,” Dugin says. “If the West is counting on economic sanctions being effective, they are wrong. I thought sanctions were Russia’s weak point, but now I see that they are not. But I also thought that military power was our strong point, and I am a bit disappointed because our army doesn’t show all the strength I believed it would show in a critical situation.”

Dugin, typically, compares the “special military operation” in Ukraine to the Passion of Christ. “Our God was crucified,” he says. “Was that the failure of our God, Jesus Christ? No, that was the sacrifice for the salvation of humanity. The beginning of this special military operation is a kind of religious act… the consequences we’ll see later. It was one of the greatest decisions in world history because, religiously and geopolitically, it was the beginning of the fight against Satan.” Given the apocalyptic stakes, the question of how many Ukrainians and Russians will die is, to his mind, a moot point.

Edward Stawiarski is a political researcher based in London. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply