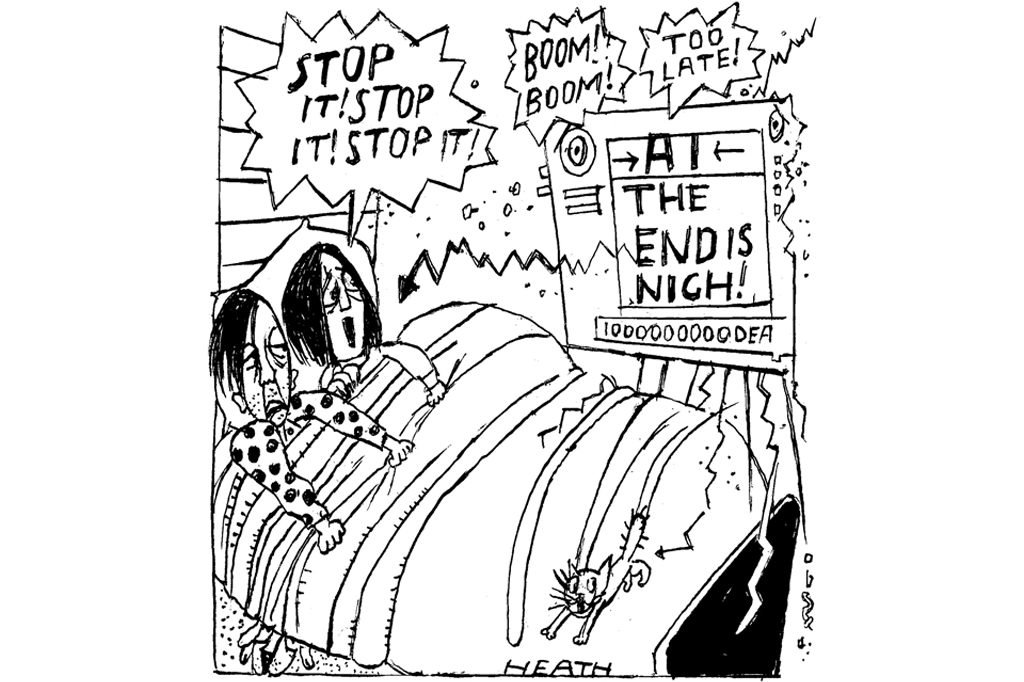

Recent advances in artificial intelligence have led many observers to worry that computers will soon replace far more jobs than imagined just a few years ago. The World Economic Forum now predicts that over 85 million positions could be lost to automation by the year 2025, many in law, medicine, accounting and other fields once thought immune to electronic substitution.

Industry experts like IBM CEO Arvind Krishna argue that the worries about this dramatic change are vastly overblown. Like every past technological innovation, he says, AI will eventually create many more employment opportunities than it eliminates, producing jobs in which a person’s productivity will be enhanced by his or her ability to use smart and dexterous machines.

But when it comes to the public sector — those who work for America’s towns, states and the executive branch in Washington — a growing payroll might not, in fact, be the best outcome. Indeed, a good case can be made that, when it comes to government, the best use of artificial intelligence is to replace as many humans as possible.

This is not to suggest that what public employees do is unimportant. To the contrary, the very idea of a civilized society implies the existence of systems for peaceably settling disputes, responding to natural disasters, managing a public pension program like Society Security, and providing other social services. Nor could anyone deny that the US is blessed with many diligent civil servants, doing their jobs as responsibly as they can.

The problem is that there are over 22 million people working for government. Two-thirds are at the local level working as police, teachers, firefighters, workers, highway maintenance personnel and other functionaries. The rest are administering federal programs in Washington, DC, and at state capitols. And the unionization of those workers, the overwhelming majority of whom pay membership dues, has created a lobbying behemoth so powerful as to effectively control most state legislatures and many in Congress. As Stanford University political scientist Terry Moe has documented, teacher unions alone tend to spend more to influence local elections than all area business groups combined, the money disproportionately going to Democrat candidates by nineteen to one.

It is bad enough that public unions lobby for increasingly unaffordable perks for their rank-and-file: bigger salaries, longer vacations, early retirement with generous benefits and lenient work rules. In a recent article for TIME on “why government unions — unlike trade unions — corrupt democracy,” attorney Philip K. Howard calculates that taxpayers currently spend two to three times more than they should for such essential services as trash collection, road maintenance and urban transit.

But public workers also use their political clout to impose a government-centric progressive ideology which is shared by only eight percent of the country. In early 2021, for example, the Illinois legislature was pressured into passing a rule which requires all the state’s teacher training programs to adopt “culturally responsive teaching and leading” standards. What this means is that anyone seeking an education credential must learn how to weave progressive viewpoints into the K-12 curriculum and how to prepare their future students to be left-wing political activists.

The millions spent by public-employee unions on ballot measures in states such as California and Oregon almost always support the options that would lead to higher taxes and more government programs. And come election time, public unions regularly mobilize their members to support the most left-wing candidates by manning phone banks, conducting rallies, canvassing door-to-door, and holding vote bundling parties.

What can be done to restore both fiscal and ideological balance to our democratic way of life? Howard himself has argued for a Constitutional challenge to the very existence of public employee unions, which at the federal level interfere with the president’s executive powers (supposedly violating Article II) and at the local level with the smooth operation of regional government (violating Article IV).

Yet many policy experts, including the Manhattan Institute’s Steve Malanga, are not convinced that the Supreme Court would necessarily agree with Howard’s Constitutional analysis. Once more, the leaders of government unions have become so adept at raising and disbursing so-called “dark money” that even tight legal restrictions on their activities might not be enough to tame their political power.

Fortunately, advances in AI suggest an intriguing alternative: deploy technologies which have been shown to provide quality public services with far fewer personnel, especially in areas like public education which by itself accounts for a full third (7,062,560) of all government workers. If you cannot do away with public employee unions, in other words, at least make them smaller and, as a result, far less influential.

One very promising technology called “blended learning,” or “technologically mediated instruction,” combines online educational materials with traditional face-to-face instruction in a way which enables one teacher to reach many more students. Originally developed in the 1960s as way for companies to educate their employees via computer, blended learning came into its own in 1999 when the American Interactive Learning Center launched software programs designed for teaching over the internet. It was widely deployed during the pandemic and, according to the Christensen Institute, has caught on with a growing number of parents who recognize it as a superior teaching method.

Looking to the future, Khan Academy founder Sal Kahn has been working with OpenAI’s ChatGPT to develop a blended learning tool called “Khanmigo,” which will allow students to ask questions about something they do not understand in the very middle of a lesson. In the case of math and science curricula, students will also be told what concepts they have failed to learn and exactly how to improve their comprehension. Kahn’s says his device will not eliminate the need for human instruction but would permit homeschooling parents and other non-professionals to easily substitute for credentialled educators, giving “everyone a tutor, everyone a writing coach.”

According to a June 2021 study published by George Mason University’s School of Policy and Management, AI will also make it possible to greatly reduce the number of government workers who perform routine bureaucratic tasks. It notes that the federal government’s General Services Administration has already developed what it calls a “leasing robot,” which manages public buildings in eleven regions across the US and processes more than $6 billion in payments each year. A related paper by Deloitte Government Trends estimates that automation could save the public sector as many as 1.3 billion human administrative hours every year.

Resolving fines and other low-level legal disputes, giving tax preparation advice, performing and interpreting medical tests, making welfare payment decisions, generating instructional publications, supervising compliance with police penalties, conducting background checks, negotiating contracts and processing claims, delivering mail, building and maintaining roads, detecting grant fraud — these are just a few of the many government functions where AI can clearly replace humans. According to Oxford academics Carl Frey and Michael Osborne, around a quarter of all modern public sector jobs could easily be automated by 2030.

It is important to understand that using AI to reduce the number of public employees is not about insensitively firing existing workers. With more than 75 million baby boomers entering their retirement years, there is no reason why a thoughtful transition to “smart government” would have to jeopardize any current staffer’s job security.

Nor would it require the average citizen to tolerate an inferior or dehumanizing experience while interacting with public institutions. Global surveys by McKinsey and Company indicate that what government’s customers care about most are “simplicity, reliability, and consistency” and that “automation can be a powerful tool to improve the efficiency and quality of [their] engagement.” As for US government, it has nowhere to go but up, as it currently ties the UK and Mexico with the lowest consumer satisfaction rank among all the countries McKinsey has studied.

Using AI to moderate the power of public unions is about being vigilant to the left’s instinctive tendency to try and solve every new social problem by hiring more government workers. Just as President Biden tried to do when he called for employing 150,000 “environmental justice” administrators to help the country achieve net-zero carbon emissions and 87,000 new agents to improve the efficiency of the IRS.

At a time when American democracy at all levels is more in the dysfunctional grip of public unions than ever before, our first response to any new challenge should be, “How can technology help us solve this problem without swelling the ranks of government workers?”