Kamala Harris is a master shapeshifter — whether through codeswitching, pandering or just being phony. One moment she’s rolling up masala dosa with Mindy Kaling on live TV; the next she’s FaceTiming the BET Awards, declaring, “Girl, I’m out here in these streets.”

Donald Trump’s bumbling attempts to highlight her cultural inconsistencies briefly shifted the election focus to Harris’s race and ethnicity — and away from far more important qualities. Perhaps it’s because her actual policy ideas have been so scant and vague that attacking them directly has proven difficult. Perhaps her chameleonic history has made anything beyond a surface-level attack difficult. But now and then there are moments where her intellectual heritage breaks through, like a salty anchovy cutting through her casually tossed word salad. Her economic policy announcement in mid-August, just prior to her coronation at the DNC, marks just such a moment.

The Harris campaign unveiled sweeping plans to enact “the first-ever federal ban on price-gouging on food and groceries” in her first hundred days. The price ceilings would extend to prescription drugs and into other industries as well, seeking to put a cap on so-called “excessive” profits. If the language sounds familiar, it is. If it sounds troubling, it ought to. If that’s surprising, it shouldn’t be.

Beneath Kamala Harris’s performative shifts lies an economic and social philosophy handed down by her father, neo-Marxist economist Donald J. Harris. And unlike unimportant arguments about her racial and ethnic background, Harris’s ideological heritage carries significant implications for her potential presidency. To borrow from the repertoire of her philosophical godmother, Charli xcx, “I guess the apple don’t fall far from the tree.”

It’s the mid-1960s at the University of California, Berkeley, a crucible of radical thought and political activism. Donald J. Harris, a young Jamaican-born economist, finds himself at the heart of this intellectual upheaval. The campus is alive with debates on civil rights, anti-colonialism and socialism. Robert Blauner and Richard Lichtman are prominent figures on campus, leading demonstrations and contributing to an academic culture centered on the examination of power dynamics, race relations, worker oppression and the core tenets of critical theory and Marxist ideology. Each would go on to etch his name in the annals of the New Left, using a blend of scholarship and activism to challenge the status quo and inculcate a generation of students into the virtues of social justice and radical change.

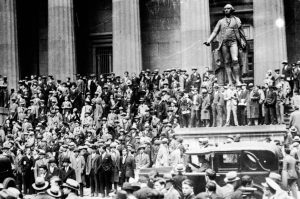

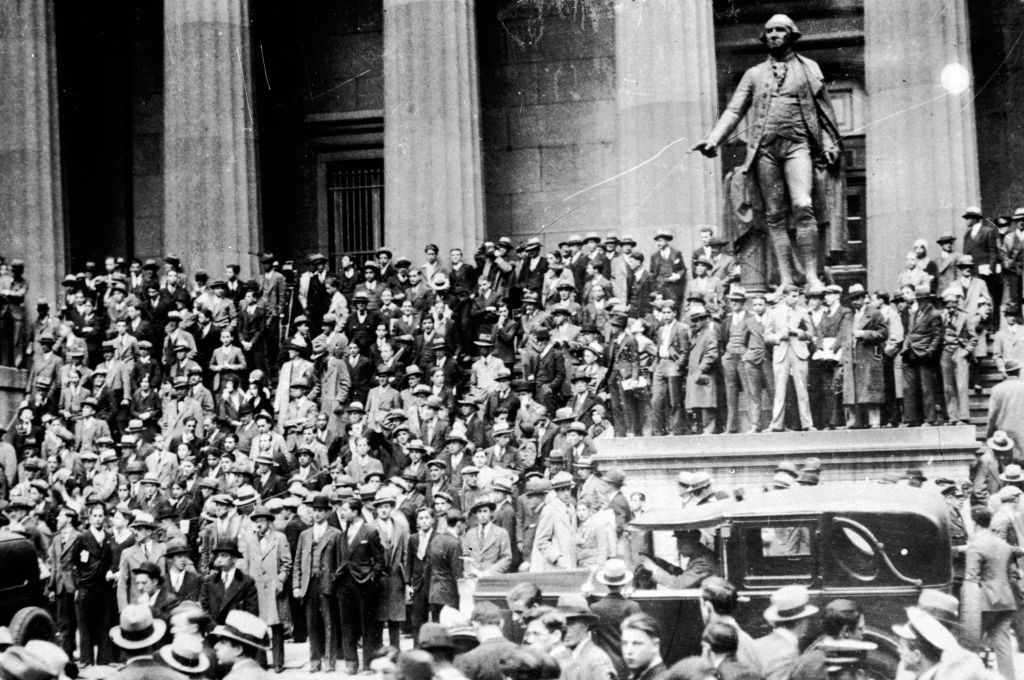

Harris, at the time a PhD student, was hard at work exploring the intricacies of economic theory. His own economic philosophy was forged in a mixture of the campus’s Marxist influence and the contemporary development of Keynesian and post-Keynesian ideas of macroeconomics. Keynes’s theories, developed during the Great Depression, emphasized the importance of government intervention in the economy to mitigate the adverse effects of economic cycles, a notion that resonated with Harris as he sought to understand and address the systemic inequalities within capitalism.

As his career progressed, Harris would ultimately borrow only the elements of Keynesianism that suggested greater government control of the economy, merging this with a philosophy that viewed the economy not as a collection of people trading value for value, but as an endless struggle between “haves” and “have-nots,” the oppressed and the oppressors, the owners and the workers. In 1972 he wrote an introduction to Nikolai Bukharin’s 1917 The Economic Theory of the Leisure Class, a critique of the Austrian school of economics from a Marxist perspective. In the intro, Harris’s admiration for Marx would reveal itself. “The standard attained by Marx’s performance would in any case be hard to equal,” wrote Harris. “It continues to have direct relevance as well to contemporary theory.”

This period cements Harris’s position as a leading figure in Marxist economics, and his intellectual journey during these formative years would seem to leave a lasting impact on his daughter, Kamala Harris, informing her perspectives on economic and social issues.

Harris’s contributions to economics, as he moved to the University of Wisconsin and eventually into full-time faculty at Stanford, would largely stem from a critical analysis of capitalist production. Imagine a worker producing $200 worth of goods in an eight-hour day and receiving $100 in pay. Harris would call the difference between the $200 value of the product and the $100 wage inherent capitalist exploitation. He would go on to apply this concept to racial divides, suggesting that systemic inequalities are perpetuated by economic structures, and to global trade dynamics, abhorring developed nations for exploiting developing countries through what he would call “unequal exchange.” Each of his arguments stands on the foundation that Marx built: a shaky one.

A more nuanced, evidence-based economic view would consider technology, entrepreneurial risk and other inputs in value creation. This neoclassical perspective (call it “capitalist” if you wish) recognizes that wages reflect labor’s marginal productivity, while profits drive investment and innovation, leading to economic growth. But Harris never embraced this complexity.

In 1974, when Donald Harris was a visiting professor there, radical leftist students fought to keep him at Stanford. A Stanford Daily article titled “Econ Dept. Loses Radical Prof” would suggest an ideological struggle on Stanford’s campus between “Marxian economists” such as Harris and more traditional viewpoints. By 1976, the ideological war had been won by Harris and his contemporaries. A student group calling itself the Alliance for Radical Change celebrated Harris’s tenure as a big step in the right direction, considering its previous concern “with the university’s apparent reluctance to hire Marxist professors.”

By the mid-1970s, Harris had become a “charismatic” and “popular… Marxist scholar” on the Stanford campus, according to contemporaneous reporting in the Daily. One article defended Professor Harris by arguing that his tenure was delayed because he had become a “pied piper lea ing students astray from neoclassical economics” and into the waiting arms of thinkers like Marx.

Donald J. Harris’s work, such as 1978’s Capital Accumulation and Income Distribution, is a testament to his Marxist commitment and disdain for capitalism. The book suggests a strong connection between inequality and growth and positions itself opposite neoclassical models, arguing that they ignore unjust balances of economic power and the class struggle, instead presenting a sanitized view that hides inequalities and instabilities inherent to the systems they support.

In his 1980 paper, “A Post-Mortem on the Neoclassical ‘Parable’,” Harris highlighted these models’ unrealistic assumptions and their failure to address the dynamics of capital accumulation. His critiques were not merely academic exercises; they were deeply ideological, aiming to challenge and ultimately overturn the foundations of capitalist economic thought. Those who champion the virtues of capitalism would argue that Harris’s work employs oversimplifications, flawed mathematical modeling and ideology to push the “critical theories” derived from the Frankfurt School and other left economic ideas into journals of modern economics — contributing to the survival of ideological remnants of Marxism in academic and policy-making circles, influencing contemporary debates and shaping societal norms.

And embedded they certainly will be, if Kamala Harris wins the presidency. Her own social and economic philosophy didn’t just fall out of a coconut tree. An economics major herself, Kamala’s academic heritage — her economics DNA — is a strong match to Donald. Anyone having read Donald’s catalog of Marxist writings would also see a resemblance in the ideas the two Harrises share.

Kamala Harris’s rhetoric often echoes the Marxist undertones of her father’s. Recall a 2020 video of hers:

So there’s a big difference between equality and equity. Equality suggests, “oh everyone should get the same amount.” The problem with that, not everybody’s starting out from the same place. So if we’re all getting the same amount, but you started out back there and I started out over here, we could get the same amount, but you’re still going to be that far back behind me. It’s about giving people the resources and the support they need, so that everyone can be on equal footing, and then compete on equal footing. Equitable treatment means we all end up in the same place.

This focus on outcomes rather than opportunities is a key tenet of Marxist thought. The policy proposals she committed to in her 2020 run for the presidency, however nebulous they may seem, reflect this ideology. Medicare for All, a single-payer healthcare system, and the Green New Deal, with its massive government investment in green energy, are aimed at addressing supposed systemic inequities through state intervention. And her more recent attacks on “excessive profits,” which she says should be regulated by way of price ceilings, echo a Marxian worldview that is not made less concerning by virtue of the policy’s fuzzymindedness.

Often this sort of cloudy policy proposal and vague rhetoric obscure our view of any specific solutions she is offering, but a Kamala Harris presidency would likely see the continued influence of her father’s Marxist legacy, emphasizing equity, government intervention and onerous economic mandates from the top down. This ideological framework could significantly shape the nation’s economic and social policies, steering them towards increased state control and economic centralization. If her recent announcements regarding taxes on capital gains and price caps mean anything, it’s that she’s far further down that path than many thought.

In the last few weeks, conservative talking heads have tried to pick apart Kamala Harris’s incoherent statements — particularly her use of the phrase “what can be, unburdened by what has been” — for hints of her leftist ideology. They needn’t look that hard. Shift focus from the inane debates on race and ethnicity and you’ll remember that none of us live unburdened by our pasts. For Kamala Harris, that burden comes in the form of an intellectual heritage that her father Donald built on the back of Karl Marx. Look closer and you’ll see an homage to it baked into every aspect of her public policy agenda.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply