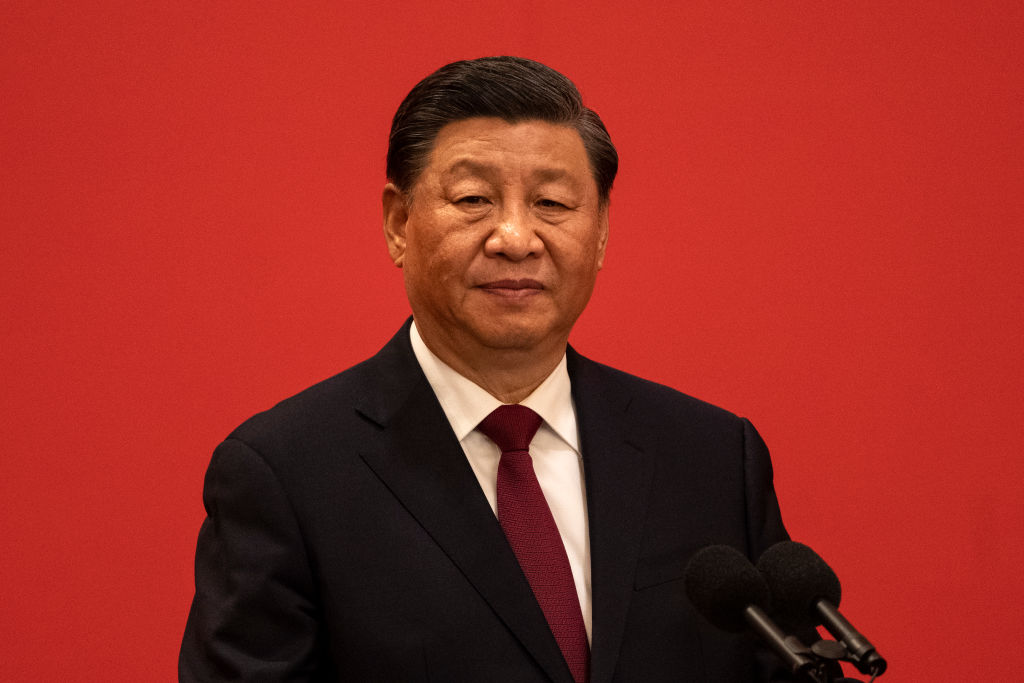

This October, at the Twentieth National Party Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), Xi Jinping was elected to a third term as chairman. “The New Mao” — so has rung the common refrain.

It’s an entirely accurate assessment. The very existence of the two-term-limit precedent that Xi has now broken was set in place by Mao’s successor, Deng Xiaoping, in 1982. The reasoning behind the term limit was to prevent the cult-of-personality chaos that Mao and his sycophants had whipped up during his untrammeled, ruler-for-life tenure at the helm of the Chinese state. Deng wanted to make China rich enough so its citizens wouldn’t care that they were not free. To do that, he needed law and order, not proto-woke Red Guards beating up middle school teachers.

And to have law and order, Deng knew he needed to keep the political turnover in Beijing moving along at a healthy clip. No more maniac geezers like Mao hanging on until the country turned into a giant communist revival tent. Two terms and you’re done.

It worked for a while — until the rise of Xi. Xi came to power in the usual fashion — murder both judicial and extra-judicial, by hook and by crook. But he has played for keeps, and double-crossed the strongest in ways few have ever dared. Like others in his situation, Xi the tyrant realizes that to lose power, or even to appear to let it slip from his grasp momentarily, is to invite instant retaliatory assassination. He will hold the brass ring until rigor mortis sets in. Just like Mao did.

The romance of the Revolution

But Xi is like Mao in another way, too. Chinese politicians after Mao have been mainly Party Central types, interchangeable bureaucratic nobodies (with the exception of the loony Jiang Zemin). The historic destiny of the Chinese Communist Party? Ha. “The historic destiny of my Swiss bank account” was the driving factor for China’s elite after Mao and Deng. Not Xi, though. Xi is a romantic. He believes in socialism with Chinese characteristics. Believes in it so much that he’s willing to risk world war to see it spread over the earth as a soothing balm.

Xi, like Mao, wants the Revolution to continue. He wants to roll the Hegelian dice with his own hand. Marx and Lenin, rise from your graves and conquer! And so, hewing to the old-school CCP version of “history,” which claims that China is fated to undo all its past “humiliations” and return to the center of geopolitics, Xi all but lowered the green flag on the final grand battle that will make China great again: the invasion of Taiwan.

As if to signal that the days of business as usual, grift-grin-retire communism were over, during the Twentieth National Party Congress, Xi had former president Hu Jintao, now a distinguished-looking gentleman with silver streaks in his hair, escorted off the stage by Party goons. Xi looked Hu straight in the eyes, half ruthless and half bemused, as the old man was yanked away, surely never to appear in public again.

So long, Hu. Copacetic communists are anathema. Xi is in charge now. And he is steering the Chinese ship of state headlong toward the Revolution’s apocalyptic ending.

The irony of Taiwan

The CCP’s showdown with “history,” and the rest of the world’s showdown with the CCP, appears to be materializing over a smallish island tucked in the grand archipelagic arc comprising also the Philippines and Japan. In a 2021 speech in Beijing on the occasion of the centennial of the founding of the CCP, President Xi warned that anyone who tried to oppose China — the implications that Xi meant “over Taiwan” were unmistakable — would get their “heads bashed in bloody.” The man sounds dead serious.

Yes, no doubt Xi wants to “retake” Taiwan. The irony of Xi’s Ahab Quest is that Taiwan has never been a part of China. “China” today is a recapitulation of the old Qing Empire (which, to add irony to irony, was not Chinese but Manchurian). Tibet, East Turkestan, Mongolia, and Manchuria are in no historical sense remotely “Chinese.” Ditto for Taiwan, in which Qing officialdom evinced only desultory interest until 1854, when American Commodore Matthew C. Perry, fresh from his gunboat-treaty journey to Japan, showed interest of his own.

Not at all worth fighting a war with Western barbarians over a barbarian island, the Qing officials concluded. “Taiwan?” the Qing bureaucrats told Perry. “Wild tribes live there. We have no control over those people.”

The Qing disavowed Taiwan, and so Perry concluded a treaty with a Taiwanese aboriginal chief instead of with Beijing. But the remolding of CCP-style “history” has now reached a fever pitch, and so the documented history of Taiwan has been thrown by the wayside.

On October 20, as the Congress was in full swing, I spoke to Seki Hei, a naturalized Japanese citizen who left China after the massacre of pro-democracy demonstrators in Tiananmen Square. Seki now analyzes Chinese politics for the Japanese national daily Sankei Shimbun.

Seki made it clear that Taiwan was the crux of the deal which was struck to allow Xi Jinping a third term as General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and President of the People’s Republic of China.

“There are quite a few people inside the CCP who are against Xi Jinping,” Seki said. “Xi won over those opposing voices and secured support for his third term by promising, among other things, to solve the Taiwan problem. Unification with Taiwan was the fundamental justification which Xi offered for the need to extend his rule for another term.

“During his keynote address at the opening ceremony of the National Party Congress,” Seki continued, “Xi drew enthusiastic applause as he vowed to unify Taiwan with the mainland. Xi made it clear that he would use force to take Taiwan if necessary.”

I asked Seki if Xi would follow through on his end of the bargain.

“The possibility of a move to take Taiwan is now very high,” Seki replied.

“Even if that means war?” I followed up.

“Even if that means war,” Seki affirmed.

The American factor

“Xi Jinping wants to avoid war with the United States,” Seki told me. “What he and the CCP are trying to do is to arrange things so that Washington does not send forces to Taiwan in the event of a Chinese invasion.

“Beijing has nuclear weapons,” Seki clarified. “China will threaten the American military and attempt to keep the American side from moving [in response to a move by China].”

The argument is sound. But I wonder how it will all play out when the shooting starts in earnest.

In early August, I attended a simulation in Tokyo, put on by the Japan Forum for Strategic Studies (where I am a research associate), envisioning Japan’s responses to a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. The simulation felt very real, not least because, as the desktop exercise unfolded in a hotel ballroom, the People’s Republic of China was launching real missiles around Taiwan, a tantrum thrown in response to Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taipei on August 2.

Former prime minister of Japan Abe Shinzō said many times in recent years, before his voice was silenced by an assassin’s bullet in July, that “an incident involving Taiwan is an incident involving Japan.” Japan is an ally of the United States, of course, and the United States is treaty-bound to defend Japan in the event of war.

The last southwestern outpost of Japan, the Senkaku Islands, lies about 100 miles off the coast of Taiwan. The sparks that set off wars can easily fly that distance.

And the sparks have been flying for a while now. Nearly every day for the past several years, Chinese “coast guard vessels” (warships painted coast guard white) have been entering Japanese waters around the Senkaku Islands, circling them like sharks going around a life raft. Japan has sent its own coast guard vessels to meet the Chinese invaders, day after day after day. It’s a recipe for regional, possibly world, war.

In 2010, a Chinese “fishing boat” (which China also uses as part of its informal attack flotilla) rammed a Japanese coast guard patrol boat. It is only a matter of time before there is another incident on the high seas around the Senkakus.

“China could not win in a direct confrontation with the United States,” Seki said. “But Xi Jinping is betting that Washington will not countenance war over Taiwan.”

There is good reason for Xi to believe that, by upping the ante to full-blown war, the Americans will back down.

“When Iraq invaded Kuwait in August of 1990,” Seki told me, “there were United Nations resolutions condemning Iraq’s actions and authorizing the use of force [to push Iraq out].”

“But Taiwan is not part of the United Nations,” Seki said. “Washington does not even recognize Taiwan as a nation. In 1979, then-president Jimmy Carter severed relations with Taiwan [in favor of China]. Washington has an obligation to defend allies, for example fellow NATO countries and the like. But Washington is under no obligation to defend Taiwan. Washington merely provides Taiwan with weapons.

“This is where Xi Jinping is focusing his attention: will Washington go to war over an island with which it does not even have formal diplomatic relations?”

Taiwan or bust

Dr. Tsewang Gyalpo Arya, the representative of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in Japan, said to me about the National Congress speech that “Xi Jinping said that ‘Resolving the Taiwan question is a matter for the Chinese, a matter that must be resolved by the Chinese.’

“If Xi is really sincere and true to what he says, he should let the Chinese people decide not the communist leadership. On the contrary, the communist leader has threatened to take over Taiwan by force and has created a warlike situation in the area around the South China Sea.”

CCP exile and dissident Jennifer Zeng, who underwent torture in China for practicing Falun Gong and who now analyzes Chinese politics from the United States, agrees.

“Militarily,” Zeng wrote to me by e-mail, “Xi Jinping has made it very clear that he will ‘unify’ Taiwan with the mainland ‘peacefully’ or with force. It is just a matter of when.”

“When?” is the million dollar question. Earlier this year, Zeng reported on what appears to be an authentic recording of a war mobilization meeting of the Standing Committee of the Provincial Communist Party Committee of China in Guangdong on May 14. The CCP seems to be making concrete preparations for all-out war over Taiwan.

“Yesterday [October 19],” Zeng continued, “while Russian President Vladimir Putin declared martial law in four occupied regions [of Ukraine], the Chinese Embassy in Ukraine issued a ‘Notice on the Transfer and Evacuation Guide and Consular Service Arrangements for Chinese Citizens in Ukraine,’ reminding Chinese people in Ukraine to be ready for evacuation at any time.

“These two incidents happened on the same day, either accidentally or by having been well coordinated.

“Another event to notice is that Chinese vice-president Wang Qishan, who often acts as Xi Jinping’s special envoy, went to Kazakhstan on October 13. Under the current quarantine policy in Beijing, this trip would make him unable to attend the CCP’s Twentieth National Congress, the most important political event for the CCP. What kind of matter was more important and urgent than the Twentieth Congress? Could it be a secret meeting with Putin to urgently coordinate issues related to the Russia-Ukraine War?

“Some people might think that the setbacks Putin encountered during the war against Ukraine would make Xi Jinping think twice about invading Taiwan,” Zeng continued.

“But, considering Xi’s personality, such information might instead cause him to speed up his invasion of Taiwan. The reason is that Xi might want to invade Taiwan while Russia is still able to hold the West in check. If Xi waits until Russia is completely defeated, then the West will have only the CCP to deal with. And that wouldn’t be too good for Xi Jinping.”

The return of the domino theory

Just after World War II, and throughout most of the Cold War, Western pundits and political leaders were wont to think of communist expansion as a parlor game. As one nation came under communist sway, the “domino theory” went, other nations would be toppled in turn. To stop the cascade, democratic states were obliged to intervene in faraway conflicts, lest the problem of communist expansion, left unchecked, spread via chain reaction.

The domino theory fell out of favor after the disastrous American war in Vietnam. But lately, over the past few years, it’s been making a comeback. Not explicitly, so far as I know. But people are seeing the world in a domino way again. The Uyghurs and Tibet are being crushed by China. Hong Kong is now a neck under Beijing’s heel. Sri Lanka, Laos, Pakistan, Kenya, Gambia, the Solomon Islands: one by one the dominos are quivering. It seems plain, almost mathematical. Taiwan will be next.

If perception is reality, then it appears that Taiwan is doomed. Xi will win the history wars by rewriting the past and the future to shape his present ambitions. Even the historical record will fall, another domino in the chain.

This may be the final irony of Taiwan. The pièce de résistance of China’s demolition of history-less globalism will likely come with the ransacking of an island so globalized that it has virtually no nation-state friends at all, a place where the faith of the globalists in “strategic ambiguity” is about to be crushed by an ethno-nationalist dictator.

Xi Jinping has amassed continental power and sits on the old Chinese imperial throne. He has no serious rivals. He lacks but one thing: Taiwan. For the sake of the world communist revolution, he will surely take it — or send millions to die trying.

Jason Morgan is associate professor at Reitaku University in Kashiwa, Japan