This week marks 15 years since the start of America’s war in Iraq. Regime change was George W. Bush’s objective, and Saddam Hussein was duly removed, tried, and executed. But Bush could not have counted on how much regime change would also come to Washington as a result of the war. It contributed to the Republicans’ loss of Congress in 2006 and to the failure of Bush’s party to keep control of the White House in 2008. Yet it did even more: it helped to give Barack Obama, an antiwar candidate—and premature winner of a Nobel Peace Prize as president—an edge against Hillary Clinton among the activist left in the 2008 Democratic primaries. As a senator, Mrs. Clinton had, after all, voted for the war.

And then there is Donald Trump. Although progressives’ dismissed Trump’s claim to have been against the war from the start, he was by far the most outspoken Republican critic of the war in 2016, even in a Republican presidential field that included Senator Rand Paul as well. In fact, the only time Trump is known to have expressed support for the war was in a Sept. 12, 2002, radio interview with Howard Stern—an interview, note, on the one-year anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, when war fever was at high pitch. In answer to Stern’s question whether he would favor a war with Iraq, Trump replied, “Yeah, I guess so. You know… I wish the first time it was done correctly.” But by 2004, when the war was still widely considered a success, Trump was staunchly opposed. His record, if not perfectly consistent, is clear enough, and a sharp contrast not only with Bush but with Hillary Clinton.

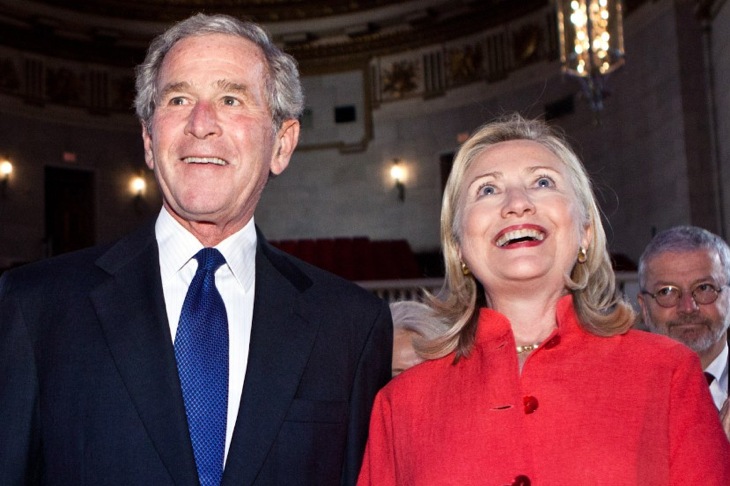

Trump, like Obama, beat Clinton. He beat a candidate from the opposing party who had a record of being more favorable toward the Iraq War, just as Obama did in 2008, and he beat all of the candidates in his own party who were Iraq hawks. George W. Bush’s war—which was also Hillary Clinton’s—wound up bringing regime change to both of America’s political parties.

The consequences of the war for ordinary Americans have been much more grave than those for the Bush and Clinton dynasties, alas. Nearly 4,500 men and women in the armed forces lost their lives. Tens of thousands were seriously wounded, and one Pentagon study estimated incidents of traumatic brain injury in the hundred of thousands. Suicides among veterans have been rife. The costs of treatment for those who did not come home whole, physically or mentally, will grow over time. The war itself cost taxpayers $1.7 trillion upfront, according to a study by the Watson Institute for International Studies at Brown University that was published just head of the war’s 10-year anniversary in 2013. The opportunity cost, when one considers how what that money could have done had it been spent at home or returned to taxpayers on the eve of the Great Recession, is at least as dear.

The strategic cost to America’s interests and Middle East stability is beyond reckoning. At the height of the sectarian violence that rushed into the power vacuum left by Saddam Hussein’s well-deserved demise, Iraq was the most violent country on earth. Millions fled across the border into Syria. And what happened in Syria, amid the ensuing economic dislocations and infiltration by fugitive Baathists and Islamist fighters? The roots of the Syrian civil war run directly back to the war that was launched on its neighbor in 2003. The roots, too, of the exodus of refugees who have since flowed out of Syria and other neighboring states into Europe lie with the Bush-Blair intervention that has so far brought a decade and a half of upheaval to the Middle East.

This was the most strategically unjustified war America has fought in at least a century. The Vietnam war was a bloodier failure in the short run, but at least in the abstract it was a matter of defending an existing regime in South Vietnam: American intervention was counter-revolutionary, as it was earlier in Korea. The first Gulf War had a limited purpose of ejecting Iraqi forces from Kuwait and restoring the immediate status quo ante. The aftermath of World War I proved cataclysmic, but it was not a war of America’s instigation, and it would have had dire consequences for Europe even if Woodrow Wilson had stayed out. The Iraq War, in contrast to all these, was not defending an existing state or ending an occupation or an example of American meddling in an ongoing conflict. There was nothing defensive about it—U.S. victory required the creation of something entirely new. It was a revolutionary project. (And no, Iraq was not like the reconstruction of Germany and Japan after World War II—those were highly organized states, which Iraq was not, and they had every reason to reorganize themselves along lines desirable to the U.S. lest their societies instead be thoroughly overturned and overrun by the Soviet Union.)”

The magnitude of the Iraq debacle must always be kept in mind when comparing Donald Trump to the last Republican president. Also to be weighed in the balance is the curious fact that Trump’s most vocal detractors among Republican-leaning pundits were virtually to a person enthusiastic advocates of the war, and many of them remain so. Perhaps it is not surprising that the Iraq War faction of the GOP should today find common cause with mainstream liberals: this is the Bush-Clinton coalition of 2003 reborn.