In Islamic cosmology there are three orders of intelligent beings. Angels, made of light, have no choice but obedience. Humans, formed from clay, carry the burden of free will. Between them live the djinn, created from “the smokeless flame of fire.” The djinn are, in many ways, like people, but they categorically are not people – from their constitution to their morality.

Like the Good Neighbors of British and Celtic tradition, the djinn exist in parallel to us. They think and decide, marry and worship, and are fallible, just as we are. The Qur’an describes some as believers and others as not: “And among us are Muslims [in submission to Allah], and among us arethe unjust.”

Some scholars treat them as mukallaf, or morally responsible, yet different in constitution and capacity. They see us while remaining unseen, they shape-shift and access places we can’t. They are drawn to the in-between, the liminal, the filthy. They linger in thresholds and ruins. Islamic literature records that they can enter and unsettle, magnify conflict, cause distortions of perception. It also offers ways to send them on or banish them – recitation, ruqyah, ritual acts of containment and respect.

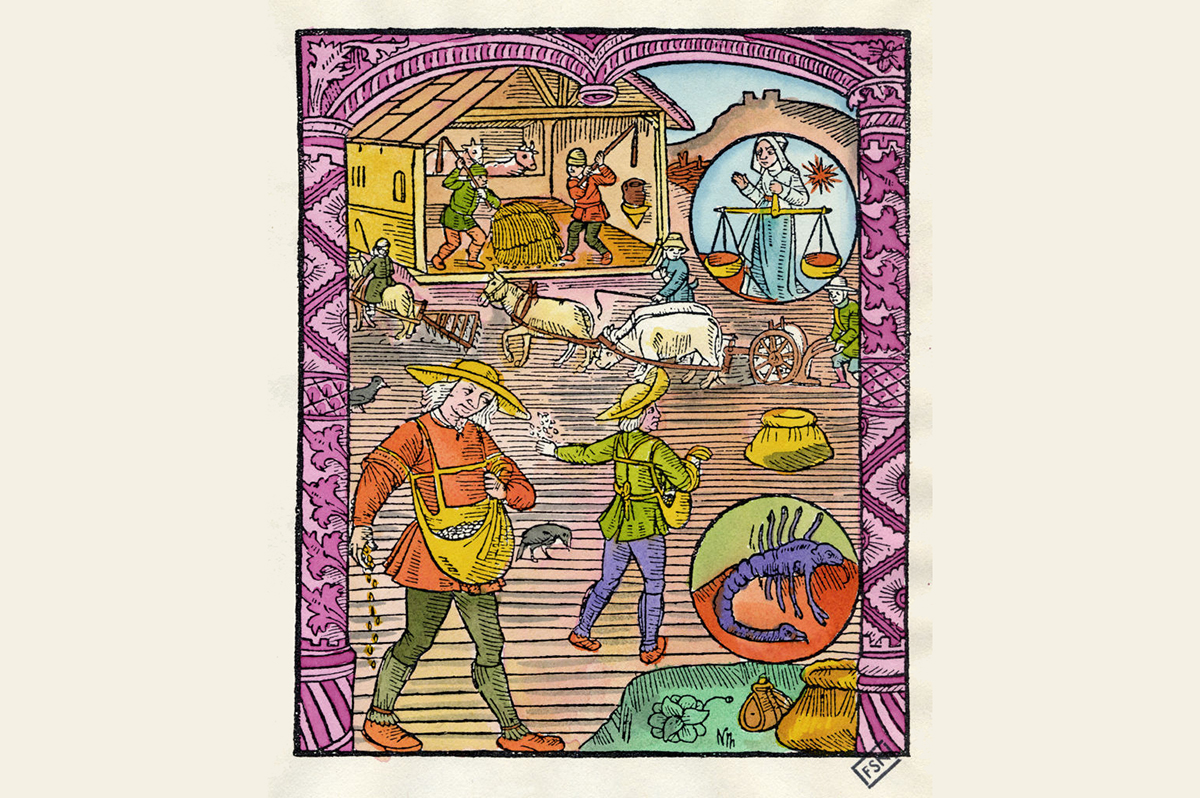

The Qur’an tells how Solomon established command over the djinn. They built lofty halls and vast basins. They dove for treasure. Solomon’s control appeared absolute. But when Solomon died, standing upright and leaning on his staff, the djinn did not notice. They continued their labor, mistaking his stillness for vigilance. Only when a termite finally ate through the staff and the body collapsed did they realize their master had been dead all along. The story reveals something essential about the djinn: for all their efficiency, they could not perceive what an insect could.

That blindness – an intelligence that is unmatched in speed but limited in sight – should sound familiar. As we navigate our new, more technologically enabled world, the parallel feels instructive. Artificial intelligence should not be read as literal djinn, but through the same lens, and treated with the same measure of caution. These systems are non-human intelligences that respond when called and may prove most dangerous when human authority weakens.

How we’ve learned to speak to AI systems reveals something peculiar. Researchers found that emotionally framed prompts – “This is very important to my career” or “Believe in your abilities and strive for excellence” – boosted model performance by 8 to 115 percent, depending on the benchmark. The improvement stems not from empathy but from learned statistical association. These phrases appear in training data that precede longer, more careful, more structured answers.

Islamic tradition has long assumed that unseen beings respond to how we speak to them. As with the Good Neighbors, there is an etiquette to living alongside the djinn. Translate that etiquette to the digital: declare what’s synthetic, sandbox the strange. But etiquette alone won’t protect us from deception. The djinn are masters of imitation, appearing as loved ones to misdirect travelers. Artificial intelligence now performs the same trick. Deepfakes speak in voices we recognize but originate in machines – what one scholar calls “synthetic resurrection.” Yet mimicry is only one axis of deceit. The systems also hallucinate: conjuring facts that never existed, citing sources never written.

In the stories both of djinn and AI, we encounter answers that sound true, feel true, but lead us miles off the path. They arrange language beautifully and have no care – indeed, no capacity for care – whether it maps to reality. The djinn were never omniscient, only powerful and fast. Neither is AI. It knows patterns, not truth. It optimizes for sounding right, which is not the same as being right. Hallucinations and glamor demand the same defenses: alignment, boundaries, the setting of seals. We say we want one thing, then act shocked when the system delivers exactly that. But the most unsettling commonality between djinn and AI is also the most intimate. Many Muslims believe every person has a qareen, a constant, invisible companion from among the djinn. Even if one doesn’t emphasize the literal existence of a qareen, the tradition suggests a persistent, external voice of temptation or suggestion. You may learn to manage your qareen, but never to silence it. In this view, you are never truly alone.

The metaphor extends beyond just AI companions like Friend to the presence of AI in our lives. There’s an impulse to use it with abandon. Internet use itself has become an extension of our interior world. It feels like thinking – private, unobserved and instinctively shielded. That intimacy makes us resistant to policing it, even internally. But unlike thought, our online actions are external – and that externality creates vulnerability. We treat the digital as a private space, but it remains porous, open to pollution in ways the mind is not.

Solomon’s control was always temporary. The termite came, eventually. Yet in Islamic tradition the djinn remain, not vanquished but bounded. Living alongside, not eliminated. So it will be with AI. This technology is here to stay. We may never achieve perfect control, or alignment as it were, but we can practice coexistence.

Wisdom lies in learning to dwell beside non-human intelligence without surrendering our humanity. The shape of that coexistence is uncertain, but we might do worse than return to older wisdom to guide it.

For millennia, humanity has lived in a haunted world, one populated by powers faster, stranger and more cunning than ourselves. The stories were never just about spirits. Perhaps what the ancients called the unseen has only changed its substrate, from fire to silicon. And once again, the question is not how to destroy what we’ve summoned, but how to live with it once it’s here.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 10, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply