Is artificial intelligence a flash in the pan? Is the boom in tech shares, which exploded with the rise in public awareness of AI, doomed to go the way of other investment bubbles over the centuries? The answer to the first question is almost certainly no, and the answer to the second very likely yes.

Investment bubbles do sometimes involve assets which have little intrinsic value, yet it is remarkable how often they begin as an entirely rational reaction to some new invention or development – an invention which outlasts the collapse of the speculative bubble, as if nothing had happened.

You only have to look at a share chart and you would assume that railways went out of fashion in the 1840s, when a mad speculative umbrella collapsed. See share charts from the early 2000s and you would likewise assume that people took one look at the internet and then swiftly went off it.

Yet the opposite is true. Railways did not just survive railway-mania, but their development accelerated through the 1850s and 1860s to the point that they came to dominate land transport in almost every industrialized country. Their supremacy was only challenged by the development of the internal combustion engine at the very end of the 19th century. Internet usage mushroomed throughout the dotcom collapse. Even tulips survived the mania of 1630s Amsterdam, becoming a popular feature in gardens the world over. This is what makes investment bubbles difficult to spot. Those who get drawn into them are often both very right and very wrong at the same time. They are right that the subject of their affections is, indeed, the future, yet in their enthusiasm they over-estimate the speed at which it will transform the world.

Moreover, they fail to spot that many companies built on the back of investment booms are winging it. They don’t own any proprietary technology and are merely clinging onto the coattails of those that do. Many of the “tech” companies which soared in value during the dotcom boom were not really technology companies at all; many were just retailers with crude websites and unviable business models.

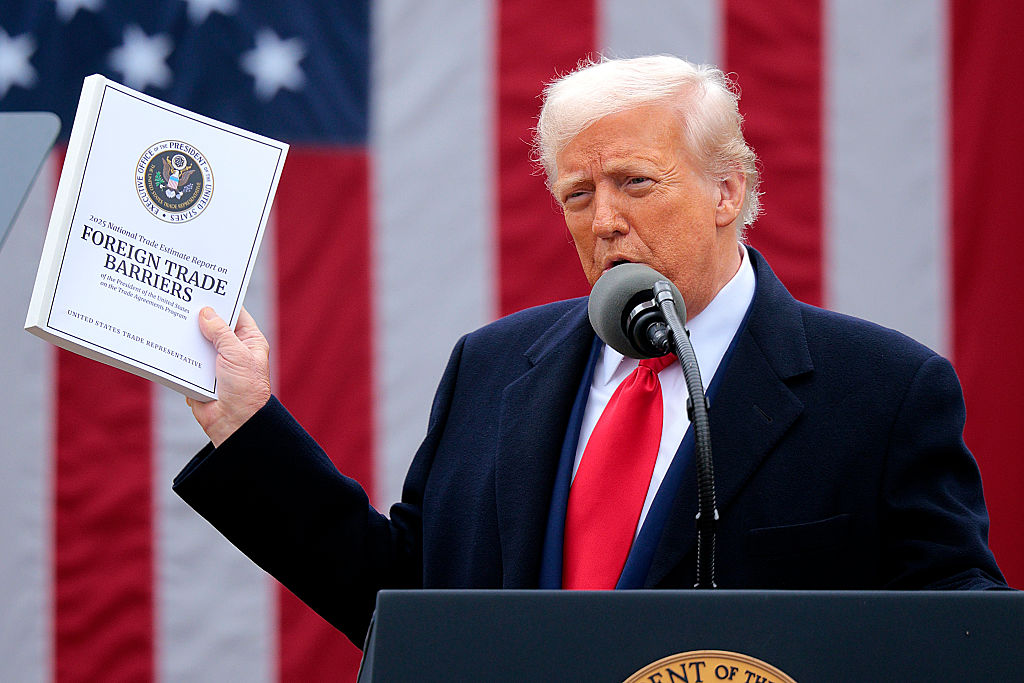

Trump would love it if a slice of Taiwan’s semiconductor industry could be relocated to the US

True, Amazon emerged and survived to dominate global commerce, but for every Amazon there were a hundred boo.coms which burned through millions without ever having to prove to investors that they had the potential to turn a profit. In a true bubble almost any company which jumps on the bandwagon can enjoy – at least briefly – a soaring share price. One of my favorite investment stories is that of the Long Island Iced Tea Corporation, which quietly did as it said on the tin until, in the midst of blockchain mania in 2017, it decided to rebrand as the Long Blockchain Corp – diversifying, so it said, from iced beverages to the technology of the moment. Its stock exploded by 400 percent thanks to investors desperate to get on board with anything related to blockchain – although the company doesn’t seem to have done a lot on the blockchain front, and ended up being delisted.

This is what makes it so difficult to deal with the current – or perhaps recent – fad for anything related to AI. Like the internet, AI could end up transforming our lives and losing investors billions at the same time. However, in the case of the AI boom there is another factor which threatens to undermine the industry and finish off the stock boom for good: geopolitics. AI – tech in general – has become a beneficiary of globalization like no other. It is almost absurdly reliant on one country, Taiwan, which manufactures more than 90 percent of the world’s higher-grade microchips, many of them made by one company, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC).

Even Nvidia, whose chips have come to dominate the AI industry, in turn relies on TSMC to make them. We found out just how reliant western manufacturers have become on Taiwan-made chips when the Covid pandemic interrupted the supply chain and starved carmakers of the chips which control almost every function of a modern car. Production lines were brought to a halt.

Yet in turn, TSMC and Taiwan rely on machine tools manufactured in the US and the Netherlands. It is a symbiosis which has been credited by some for maintaining an uneasy standoff between China and Taiwan. While China, it seems, would love formally to annex the island and has been making all kinds of physical and verbal threats to that end, an invasion would risk undermining the chip industry on which it, as well as western countries, relies. Taiwan’s unique position is described by some using the term “Silicon shield,” asserting that the semiconductor industry provides an invisible deterrent against Chinese invasion.

‘I think it’s another article written by AI.’

On top of that come Donald Trump’s trade wars. So far, the President has blown hot and cold on imposing tariffs on semiconductors. His administration has been reviewing what levy, if any, to impose on the industry. Trump would love it if a slice of Taiwan’s semiconductor business could be relocated in the US. He should, at least partially, get his way within the next few months as TSMC’s delayed new $6.5 billion manufacturing capacity in Arizona starts to produce chips.

The company has a further two factories planned, in addition to the one which has been under construction since 2020, to be opened by the end of the decade. That is exactly what Trump’s tariffs were launched to achieve: to stimulate the reshoring of manufacturing to the US. Whether it will happen quickly enough to keep the tech boom afloat is another matter.

To understand the position the industry is in, imagine if, at the time of the 1973 oil crisis, the Middle East had controlled 95 percent of the world’s oil production and that power stations as well as cars and airplanes were reliant on it. In fact, at that time, the US accounted for just over half of global oil production and many countries had electricity grids based on locally mined coal. Even so, the oil crisis sparked massive inflation and caused a global recession.

Without Taiwanese semiconductors the tech industry simply cannot function. The whole tech boom is predicated on confidence that China will not invade and that Trump will stop short of harming the engine room of the US economy.

What we have seen so far this year, with – at the time of writing – the NASDAQ down around 20 percent, is a correction rather than a crash; it merely takes the index back to where it was last August. We are not seeing the mass implosion of tech companies on a scale like the dotcom collapse in 2000. It is the kind of hiccup from which the tech boom has recovered several times before, most notably between 2021 and the beginning of 2023 before AI and Nvidia overtook the likes of Google and Apple as the biggest growth story.

But it is possible to see a different theme emerging from the fallout of Trump’s trade wars. What if we are heading for a new age of autarky? In that scenario, the industries and businesses which come to dominate will be those which are swiftest and most effective at shortening their supply chains. If you can reshore your manufacturing you will have a distinct advantage over a business which is caught napping.

This is where you wonder if the US really will be the biggest loser from Trump’s trade wars, as markets seem to have assumed so far. It might be tempting to think that Europe will finally start to prosper over the US as the latter’s industries are hamstrung by tariffs imposed on imported raw materials and components.

Yet the US has a serious advantage: it is far easier to open and close factories here than it is in Europe. In France, for example, you have to beg a workers’ council for permission if you want to close a factory. As a result, the country is full of under-productive factories working at half-strength. Make it difficult to fire workers and you make it unappealing to hire them, too.

Moreover, in the US there is a greater public appreciation of inward investment. Phoenix has welcomed TSMC’s new facilities with open arms; by contrast, environmental protesters tried to undermine Tesla’s Berlin factory from the beginning, objecting to the company chopping down trees for the project – and that was well before Elon Musk started his dalliance with Germany’s far right.

Investors would be rash to bet against the US, and in particular its tech industry, in spite of what seems like an act of national self-harm. The US is culturally much more suited to thrive in times of great upheaval, just as it did after Covid – on that occasion unemployment initially surged far more in the US than in Europe, where companies were granted much more protection.

One of the astonishing statistics from the Covid era was that in 2020, Britain suffered its smallest number of company insolvencies in three decades, despite half the economy being closed down, as unviable businesses were propped up with public money. But by the end of 2020 it was a totally different story after the US turned into a remarkable job-creation machine.

There is a case for saying the tech boom is over, that it is a speculative bubble which has run its course. But there is a stronger case for saying that it will rapidly recover from this year’s hiccup. Indeed, by encouraging a more diversified supply chain, as seen in TSMC’s expansion into the US, the tech industry may come out of it stronger.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply