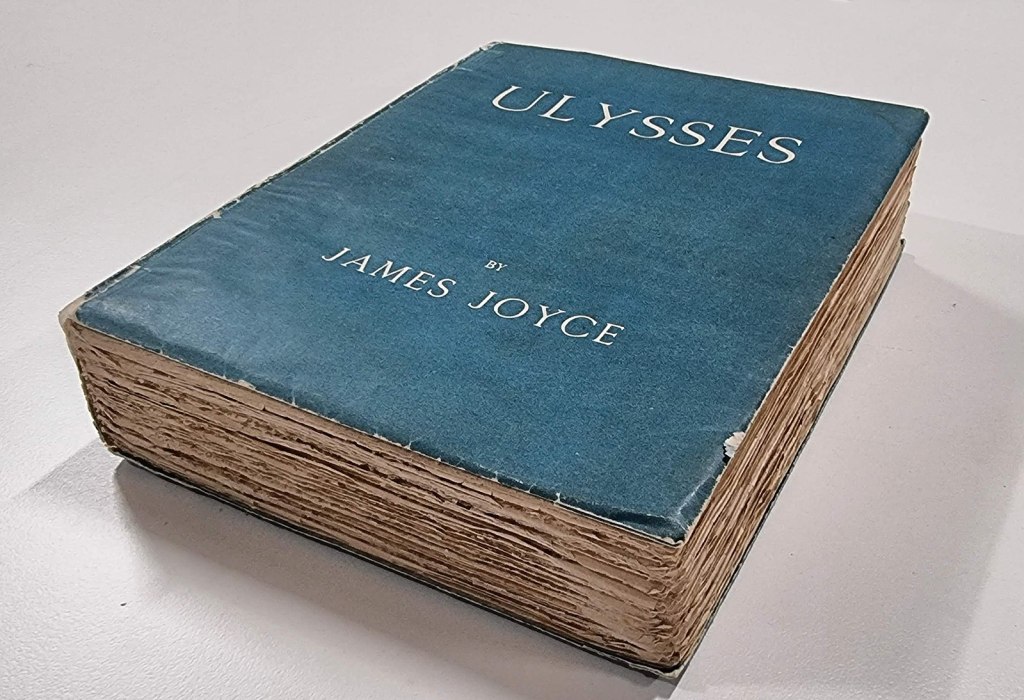

I have twice tried and failed to finish James Joyce’s Ulysses. Perhaps the third time will be the charm, if there is a third time.

Tomorrow marks the novel’s 100th anniversary. After being serialized in the Little Review between 1918 and 1920, it was published in full in Paris by the English-language bookstore Shakespeare and Company.

The novel takes place in Dublin on a single day, but it was written in Trieste, Zurich and Paris. Catherine Flynn takes stock of the novel’s debt to the European avant-garde in a jargonish but nevertheless worthwhile piece in The Irish Times:

The Dadaists attacked not only national identity but also sense itself. Understanding rational discourse as complicit in the slaughter of the war, they practised a mode of live performance that assaulted their audiences with multiple genres, languages and voices. In contrast to Futurism’s clear principles, Dada refused any guiding idea. Dada, “yes yes” in Romanian and “hobby horse” in French, meant nothing, Ball asserted.

Joyce, a British subject on enemy territory when the war broke out, moved with his family to Zurich in 1914. They lived close to theatre at Speigelgasse 1 where the Cabaret Voltaire began in 1916 but the Dada movement, like Futurism, was impossible to ignore. As Dada artists used found materials in performances and collages, Joyce recast in Ulysses the physical details and ephemera of June 16th, 1904. Whereas Dada’s emphasis on spontaneity and chance differs fundamentally from his painstaking writing and rewriting, the intended effect of Dada’s barrage of words resembles the effect of the Ulyssean multiplicity of references.

But far better — perhaps the best single essay on the novel — is Edna O’Brien’s 1999 piece on the “labors of Ulysses” for the New Yorker:

Joyce left Ireland—that “scullery maid of Christendom”—in 1904, to escape its confiningness, and went with his sweetheart, Nora Barnacle, to teach in a Berlitz school on the Adriatic coast, first in Pola, and then in Trieste. Being of a restless disposition, he soon tired of Trieste, with its drab provincials and a bora wind that turned men with ruddy complexions, like his, into butter. Rome, the Eternal City, suited his destiny, and, moreover, his hero Ibsen had wintered there. He found a job in a bank writing letters to foreign customers for nine hours a day.

In truth, anger over his financial straits and frustration at not having his short stories published was hotting up in him as he searched for that “fermented ink” to stir his bile, the way shots of absinthe sizzled his brain. It was in Rome, in 1906, that he first conceived of Ulysses—”that little epic of the Irish and Hebrew races.” From there, he voiced his literary manifesto in a postcard to his brother, Stanislaus. He wrote that if he were to put a bucket down into his own soul’s sexual department he would haul up the muddied waters of Arthur Griffith, the leader of Sinn Fein; Shelley; Ibsen; St. Aloysius; and Renan, the biographer of Christ. In short, cerebral sexuality and bodily fervor were universal: there was no such thing as a pure man or a pure woman. Joyce was about to do through words what Freud, whom he reviled, was attempting to do with highly strung patients in a cultivated but stifling Vienna.

Terence Killeen remembers when the novel “languished in publishing limbo”: “Given its effective exclusion from the major English-language markets, Ulysses seemed doomed in advance never to appear.” And in the Wall Street Journal, Jeffrey Myers praises Joyce’s “virtuoso style and rhythm,” which “convey the idiosyncratic thoughts of each character”: “Bloom has rapid, staccato ideas, vivid and bright, rapidly shooting out in all directions. Molly has a sensual rhythm like the waves of a swelling sea. Gerty has schoolgirl speech and clichés of romantic novels. The speech of Stephen Dedalus, alienated from his father and the substitute for Bloom’s lost son, is poetic and abstract, learned, proud and sad.”

In other news

Speaking of Joyce, you may also wish to know that the Irish Post released two new stamps to mark the novel’s centenary. You can buy them here.

Ian Cawood reviews a well-researched history of British corruption:

As Mark Knights explains in his significant new study of corruption in Britain and its empire between 1600 and 1850, such concerns are not new. The scholarship on display here is remarkable. Knights has a forensic command of the detail of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century politics, administration, ethics, philosophy and social attitudes, and a mastery of the complex secondary literature on the period. Unlike previous scholars, such as William Rubinstein and Philip Harling, Knights is not outlining a historical teleology of the decline of corruption. The scandals surrounding the ruin of the Tory MP George Hudson in the early 1850s, the failure of the Commissariat to provide adequate supplies in the Crimean War and the disfranchisement of Wakefield and Gloucester in 1860 for the blatant bribery of voters would make a mockery of any claim that corruption had been eliminated from mid-Victorian Britain.

In praise of Jean d’Ormesson’s The Glory of Empire: “The great babel-like tower of fantastic history is if nothing else, exceptionally lovely. The clear and elegant style of good narrative history writing is mixed with a poetic and philosophical reflection.”

The year is 700 BCE, the place is the Black Sea. You find yourself in land east of ancient Greece. To your right lies the tumultuous sea, to your left a mountain range. In between: fertile lands where hazelnuts grow, berries, wild sage and oregano. You are riding through the shallow marshes along the coast, with no more than the occasional heron, wild horse or hawk crossing your path. When suddenly, you are attacked by a fierce band of warriors on horseback. According to the Greek scholar Herodotus, this is what happened to a tribe of Scythians. They were a community of nomadic horse-archers living on the Black Sea around the 7th century BCE, who one day found their horses seized by a mysterious fighting force. Only once the young men had engaged and killed some of them, did they realise that their opponents were women. Female warriors called Amazons, who “had nothing beyond their weapons and their horses” and “devoted their lives to hunting and raiding”.

Who is buried in W. B. Yeats’s grave? Probably a clubfooted Frenchman: “Yeats’ grave is one of the most visited in Ireland, with up to 80,000 people making the pilgrimage to Drumcliffe graveyard every year to read that iconic tombstone inscription (‘Cast a cold eye / On life, on death. / Horsemen pass by’) and pay their respects to . . . a club-footed Frenchman. Or perhaps several of them. Yes, this is your annual reminder that it is highly unlikely the bones buried underneath this very cool tombstone are those of W. B. Yeats.”

Francis Bacon behind the iron curtain: “[James] Birch’s picaresque memoir, Bacon in Moscow, written with help from the journalist Michael Hodges, is the first book to be published by Cheerio, an imprint established in partnership with the estate of Francis Bacon (“cheerio” was Bacon’s preferred drinking toast) – and, yes, who would have thought, considering the dozens of books about the artist that already exist, there would be anything left to say? But this really is a peculiarly evocative and authentic title: one that, at moments, brings Bacon to life far more vividly than do, say, the several hundred of pages of Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan’s biography, published last year.”

Can medieval sleeping habits help modern insomniacs?

The romanticization of preindustrial sleep fascinated me. It also snapped into a popular template of contemporary internet analysis: If you experience a moment’s unpleasantness, first blame modern capitalism. So I reached out to Roger Ekirch, the historian whose work broke open the field of segmented sleep more than 20 years ago. In the 1980s, Ekirch was researching a book about nighttime before the industrial revolution. One day in London, wading through public records, he stumbled on references to “first sleep” and “second sleep” in a crime report from the 1600s. He had never seen the phrases before. When he broadened his search, he found mentions of first sleep in Italian (primo sonno), French (premier sommeil), and even Latin (primo somno); he found documentation in Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, and Latin America.

Michael Dirda goes to the annual Baker Street Irregulars banquet in New York for Sherlock Holmes aficionados: “A little after 6 on Friday evening, decked out in my thrift-store tuxedo, I hurried to the Yale Club for the weekend’s main event — the cocktail party and banquet. Hollywood’s go-to ornament and jewelry designer Maggie Schpak, whose pieces can be seen in Star Trek, Raiders of the Lost Ark and Pirates of the Caribbean pinned on my badge and then showed me the tiara she had created for the next day’s raffle.”