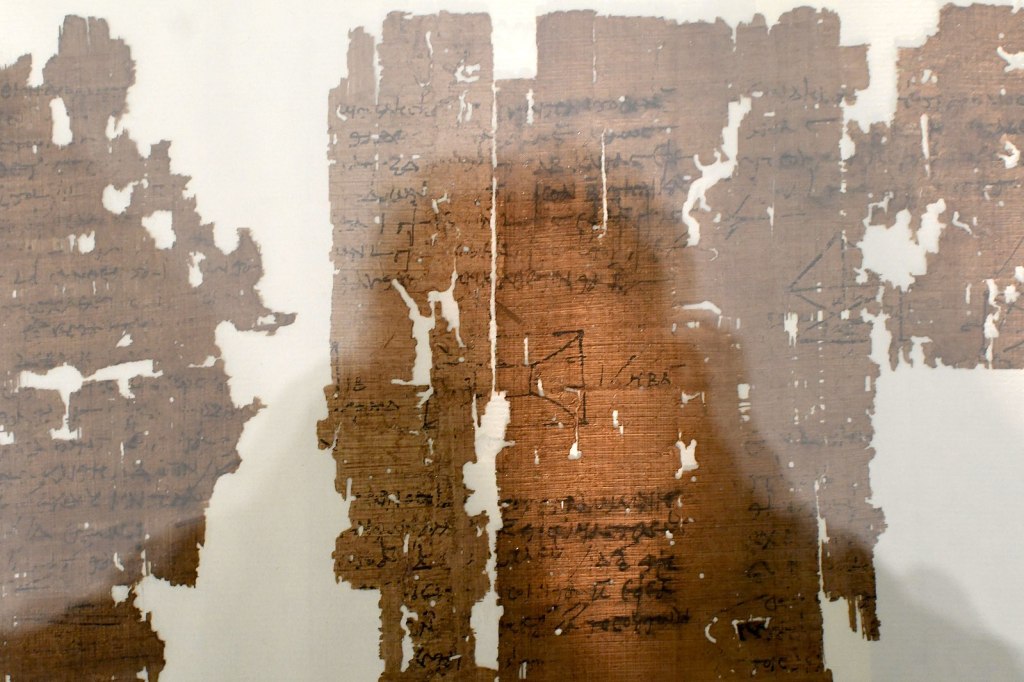

In a recent article in Science, Mike Kestemont and Folgert Karsdorp employ the “unseen species model,” which is taken from ecology, to estimate the number of medieval manuscripts that have been lost over the years. They estimate that we have lost a whopping 90% of medieval manuscripts containing heroic narratives.

In the Guardian, Laura Spinney notes that it isn’t only medieval manuscripts we’ve lost. We have 543 early modern plays produced between 1576 and 1642, but these likely “represent a fraction of all those produced”:

Another 744 that certainly existed have been lost, and hundreds more were probably written to fill the repertory calendar, of which no trace remains. Some plays were translated into German and performed on the continent by travelling English players, including works by Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe. At least one play written for the English theatre, whose author is unknown, only survives in German – The Comedy of Queen Esther and Haughty Haman – and there may be others.

Spinney goes to state that “we can’t console ourselves that the plays that do survive were necessarily the best, or at least the most popular”:

David McInnis crunched the numbers based on the meticulous book-keeping of one London impresario in the 1590s, Philip Henslowe, and drew the following conclusion: “Lost plays performed at least as well as, and usually better than, the plays that have survived. They are definitively not inferior, they were good money-makers, and they have been lost for a variety of reasons that aren’t attributable to quality.”

Well, of course we don’t know that the plays we have now were “the best.” I don’t know anybody who would be so foolish as to claim this.

But we can say that most of the plays we have today were popular or thought great (or both) because someone went to the trouble of copying or printing them, and that most of the works we have today were likely among the best and most popular because of the number of copies made. On the whole, mediocre work usually has a smaller chance of survival.

In other news

James Panero goes to the highly praised “Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents” show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He isn’t impressed: “While containing passages of the specific, the paintings rise above the regional and anecdotal to speak to the broader themes of childhood exploration, interpersonal relations, and natural wonder. Mystery and peril vie against ingenuity and observation . . . And yet, this major exhibition leaves the artist foundering. Political baggage has been piled high. Much like The Gulf Stream (1899, reworked by 1906, Metropolitan Museum of Art), the masterpiece at the center of the show, the tiller has broken, the mast has snapped, and the cargo will not make it to shore.”

Shira Telushkin reviews the Wassily Kandinsky retrospective at the Guggenheim in New York: “There is a moment, as one rounds the final span of the four-level exhibit of Wassily Kandinsky’s works at the Guggenheim in New York, on display through September 2022, where the art gives way to an almost transgressive sense of intimacy.”

Dennis Duncan tries to make sense of the work of Franciszka and Stefan Themerson:

“This short film is an experiment designed to use the medium of the screen to create for the eye an impression comparable to that experienced by the ear.” While the caption scrolls upwards, a soprano sings from Karol Szymanowski’s Słopiewnie cycle. This is The Eye and the Ear (1944), produced by the Polish Film Unit, which operated out of London in the later years of the war. Other films made by the unit were unambiguously propagandist: documentaries about Polish soldiers and pilots stationed in Britain, happily integrated, sharing in the Allied war effort. The Eye and the Ear is an anomaly: ostensibly apolitical and avowedly experimental, with techniques – layering, photograms, animation – drawn from the avant-garde. As the opening text fades, a series of black and white images of droplets appear, radiating waves that are sped up, slowed down, superimposed. The shadow of a hand enters the frame, circles of light bulging as its fingers break the water’s surface. The effect is hard to parse. It looks surreal but it isn’t: rather, the film is an attempt to find some congruence between the visual and the aural, to make them mutually translatable . . . For the Themersons, and for Stefan in particular, there was always something in between about their achievements. Translators and publishers of the European avant-garde, mediators between science and literature, music and film: if anything defines their work, it’s the idea of transit, a quixotic alchemy that tries to turn one thing into another even when the conversion is intrinsically nonsensical.

A new history of paganism: “While Hutton’s iconoclastic masterpiece The Triumph of the Moon (1999) essentially denied contemporary neopaganism any convincing claims to historical continuity, Hutton has always balanced his scrupulously polite eviscerations of neopagan wishful thinking with an insistence that the history of paganism nevertheless matters, even if the real history is not the one many of us expected. In his latest book, Queens of the Wild: Pagan Goddesses in Christian Europe: An Investigation, Hutton returns to a key question posed in his work in the 1990s: Was there really any continuity or survival of paganism in the Christian Middle Ages?”

The Académie Française takes aim at English tech jargon again: “While some expressions find obvious translations — ‘pro-gamer’ becomes ‘joueur professionnel’ — others seem a more strained, as ‘streamer’ is transformed into ‘joueur-animateur en direct’.”

The branches of the United States military have large art collections: “The coast guard makes a greater effort than other US military branches to display its holdings, which have grown to more than 2,000 pieces in the 41 years since the programme launched. The Marine Corps, which has collected more than 11,000 works since 1942, displays pieces in a room at the National Museum of the Marine Corps. The army’s 35,000-piece collection, begun during the First World War, is almost entirely in storage at Fort Belvoir, Virginia. The US Air Force Art Program, started in 1950 and numbering around 9,300 pieces, is accessible primarily through the air force website.”

Speaking of the military and art, Alissa Wilkinson provides a short history of the relationship between Hollywood and the United States armed forces: “The American movie industry and the American military have had a long, well-documented, and, on the whole, mutually beneficial relationship since before World War II. Certainly, movies about war and its effects have been made without the aid of the military. But the military has often seen opportunity in the movies: for boosting the morale of the public, altering the popular image of wars and soldiers, and encouraging young people to enlist.”

Paul Dean revisits the work of Alain Robbe-Grillet:

It’s safe to say that the centenary of Alain Robbe-Grillet’s birth, this year, will not be widely celebrated even in France, other than by his wife, Catherine, who is still alive at the age of ninety-one. The outrage which greeted the publication of his final novel, Un roman sentimental (2007)— which the publisher issued with pages uncut, swathed in shrink-wrapping and with a warning sticker—damaged his already equivocal reputation almost beyond repair . . . It must also be conceded that, even before the recent surge of interest in Francophone writing, which emphasises more diverse cultural and gender issues, much of Robbe-Grillet’s work had dated badly.