There was a time when the relationship between the United States and China had a bright future. While bilateral relations have never been particularly rosy since the two countries formally established diplomatic ties on January 1, 1979, US and Chinese leaders have long worked on the assumption that they had much to gain by deepening their cooperation and, if possible, expanding it to new heights.

This was a widespread sentiment in Washington, reflected in speeches given by presidents from both parties. “I know there are those in China and the United States who question whether closer relations between our countries is a good thing,” President Bill Clinton told students at Beijing University in June 1998. “But everything all of us know about the way the world is changing and the challenges your generation will face tell us that our two nations will be far better off working together than apart.” President George W. Bush was just as amicable four years later, when he addressed another room of students at Tsinghua University: “China is on a rising path, and America welcomes the emergence of a strong and peaceful and prosperous China.”

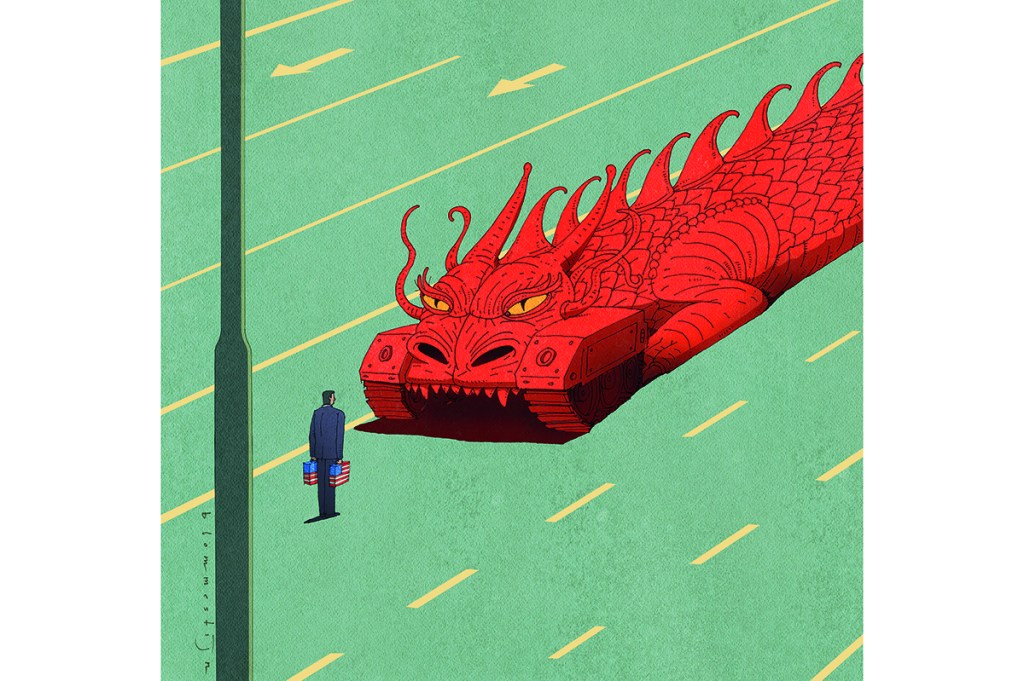

Decades removed, those remarks strike many as naive. Yesterday’s atmosphere of guarded optimism has been replaced by much greater suspicion. The US and China are the two largest military spenders and compose approximately 43 percent of the world’s economic output. Yet the two great powers remain ready to leap at each other’s throats. The US Defense Department labels China its principal competitor and “pacing challenge,” while the Chinese army, the PLA, has devoted decades to re-arming and modernizing to balance against, if not break, US dominance in Asia.

Given the geopolitical circumstances, it’s no surprise that American politicians of all ideological stripes default to getting tougher on China. “In the US, politicians have long realized that using China as a punching bag tends to increase their levels of support, reflecting deep anti-China sentiments in the country as a whole,” says Lyle Goldstein, the director of Asia Engagement at the Defense Priorities think tank (where I am a fellow). “The Chinese leadership is aware of this phenomenon and they are duly pessimistic about the bilateral relationship.”

The Chinese have reason to be depressed. The 2024 Republican presidential primary is a who’s who of China hawks advocating for economic controls, tariffs, US military buildups in Asia and wholesale campaigns to rid American universities of Chinese Communist Party influence. Former New Jersey governor Chris Christie has suggested that if China isn’t stopped, our grandchildren could be living in a world where the CCP calls the shots. Former US ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley describes China as an enemy with a grand plan “to cover the world in communist tyranny.” Florida governor Ron DeSantis frequently touts his decision to ban Chinese purchases of agricultural land. Former president Donald Trump, who spent his first term bashing China for the coronavirus and launching a trade war, is promising more tariffs on Beijing and a phase-out of US imports from China, including on goods that are deemed essential.

President Biden may not be as rhetorically prickly as his GOP competitors, but his China policy is just as stringent as Trump’s. In certain respects, Biden has even broadened some of Trump’s own policies. Not a single Trump-era China tariff has been removed. The Trump administration targeted Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei with a raft of export bans, the most significant of which involved cutting the company off from the US components and technology needed to manufacture its smartphones. In October 2022, the Biden administration essentially took the Huawei bans and applied them to China’s entire economy to prevent Beijing from utilizing US technology for weapons development.

On the diplomatic front, Biden has brought the China question straight to the heart of America’s traditional alliances and partnerships. Warily eyeing a rising China, Japan is in the process of doubling its defense budget over the next five years. South Korea is strengthening its relationship with Tokyo at Washington’s urging. The US and the United Kingdom are working to help Australia produce its own nuclear-powered submarines, which will allow Canberra to become a formidable military partner in the event of a hypothetical conflict with China. The Biden administration has also negotiated a deal with the Philippines that increases the number of bases the US can access from five to nine, some of which face the Taiwan Strait.

Although Biden insists he doesn’t want to contain China, his policies would, in effect, do precisely that. In June 2023, he rolled out the red carpet for Indian prime minister Narendra Modi and feted him with an official state visit in the hope that the Indian leader could be persuaded to serve as a force multiplier for US ambitions in the Indo-Pacific. Biden’s desperation to contain China has reached such an extent that not even news of suspected Indian government collaboration with multiple assassination plots in Canada and the US was enough to push the White House to reassess its approach. Biden talks a big game about the importance of democratic values and human rights, but he has demonstrated time and again that when it comes to China, he’s more than happy to shove these concepts aside if it means enhancing Wash- ington’s geopolitical position. You need look no further than his September visit to Vietnam, an authoritarian power with a habit of locking up political dissidents, but a Southeast Asian nation he nevertheless wants in his corner.

Fortunately, this twenty-first century cold war has stayed cold for now. The US national security bureaucracy and Congress may be full of China hawks, but the administration is not eager for a shooting match over Taiwan or the South China Sea. Even thought leaders behind a more assertive US posture toward China preface their recommendations on the urgency of maintaining balance and tranquility with Beijing. As Elbridge Colby, a former senior defense official in the Trump administration, told me, “Détente is possible, and indeed in my view the ultimate goal, but it will only be feasible from a position of collective strength.” Unnecessary provocations, Colby added, should be avoided lest the rivalry between the US and China turn into an outright confrontation.

To call this sound advice would be an understatement. US-China ties have been anything but predictable over the last eighteen months, instead resembling a roller coaster ride — including the moments of nausea. After then-Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s ill-advised visit to Taiwan in August 2022, China cut off contact with the US, suspended working groups on everything from trade to narcotics and authorized large-scale military exercises that looked like a rehearsal for a future invasion of the island. Biden’s meeting with Xi three months later was supposed to hit the reset button but that jammed as soon as the US spotted a Chinese surveillance balloon floating gently across the continental US. Meetings to operationalize what Biden and Xi agreed on were postponed indefinitely.

The latter half of 2023 was somewhat more positive. Secretary of state Antony Blinken, Treasury secretary Janet Yellen and commerce secretary Gina Raimondo flew to China to meet their Chinese counterparts in an effort to re-establish ties. Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi flew to Washington in October, the first such visit in five years. Biden and Xi met again in November, this time in San Francisco, where they ordered a re-opening of the military-to-military talks that had languished since the previous year. There’s even talk of US and Chinese officials spending time in 2024 on arms control, with the possible negotiation of a bilateral missile launch notification regime on the docket.

Some experts are not overly enthusiastic. “The United States and China are at odds on many issues and, as a result, I do not expect that the bilateral relationship will move to détente, let alone rapprochement, any time soon,” David Santoro, president of the Pacific Forum, says. “We’re likely to see more of the same and there is the possibility of the situation deteriorating, perhaps even leading to confrontation.”

Santoro is likely correct. The differences between the US and China are systemic and unlikely to be resolved regardless of how many phone calls or meetings are scheduled. The fact that a very slight melting of the ice is occurring at the same time the 2024 US presidential campaign is heating up is hard- ly promising. Biden and whoever emerges as the Republican nominee will spend months on the campaign trail talking up their anti-China bona fides and painting the other as weak and irresolute. As Goldstein emphasized, US and Chinese officials are already pessimistic about the relationship in general and are cautious about expending political capital.

If we’re lucky, US-China relations in 2024 will remain as they are right now: stable enough that the two superpowers can continue to work through some differences, even if both acknowledge that the major economic and foreign policy divisions aren’t going away. The only other realistic alternative is hypersensationalism, something responsible policymakers in Washington and Beijing can’t afford.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply