Local chief Panta wore a government-issue khaki uniform with epaulettes, beret and swagger stick. On a pleasant stroll to our farm springs, he observed how plenty of blood had been spilled over this water. We sat on the glassy-smooth black rocks around the water pools and the chief retold for me a story more infamous in its day than the Happy Valley tale of Lord Erroll’s murder, but now completely forgotten.

Welshman Dicky Powys, from a family of authors and philosophers and cousin of our ranching neighbor Gilfrid, arrived in Kenya in 1931 to farm. Young Dicky learned the local Maasai vernacular fluently and got on with everybody. His employer had rented pasture in Laikipia around our springs for a vast flock of sheep and Dicky pitched camp here. One dawn he set off on his white pony to scout for fresh grazing. Hours later, the horse returned riderless. Dicky’s campmates went looking for him and two days later they found vultures and signs of a commotion in the dust. On one side was a blood-spattered hat, ripped shirt, khaki trousers bloodied and covered with animal hairs. Scattered around were ribs, arms and a severed left foot still in its boot — but no skull.

Then as now, lions were common. Dicky had recently shot two of them. The coroner decided Dicky’s pony had shied from a lion, throwing the rider who broke his neck. Scavengers had devoured the remains. Weeks later a Samburu named Kiberenge appeared at the local police station claiming Dicky had been murdered and that he knew where the victim’s skull was lodged in a tree. The British said he was lying and sentenced him to five months’ hard labor. Then a skull did turn up, with a gold filling in one tooth just like Dicky had. On his release, Kiberenge vanished and was promptly murdered. When two more Samburu witnesses appeared, the British flogged them with a hippo-hide whip. After that people shut up.

At this time the Samburu pastoralists were holding circumcision ceremonies for a new generation of warriors called the Kiliako. Unless the Kiliako blooded or “washed” their spears, they weren’t considered marriageable. They murdered thirty-two men in the district and were enthusiastic about butchering more, but to everybody’s dismay the British now outlawed the joys of warring, cattle rustling and abducting women. Into this scene walked Kalondjan ole Oduma, an obese figure the Samburu believed to be a powerful wizard, or laibon. At dances in the cattle camps, he decreed the killings should continue. Youths painted with ocher, their blades flashing in the sun, reeled in the air before the lines of beaded maidens — and everybody was happy again.

In 1933, the Laikipia rancher Gilbert Colvile wrote to Kenya’s governor: “One man is behind the whole of this series of crimes: the Samburu laibon ole Oduma.” Colvile was fluent in the Samburu dialect and farmed close to my home. Known as Nyasore — the Thin Man — Colvile lived happily as a Samburu with his sheep and cattle in a mud hut full of dogs and rawhide skins. The British finally listened to Nyasore and arrested the wizard. Suddenly the witnesses reappeared, Kiberenge’s statement was dusted off and a picture of Powys’s death emerged.

The night before a full moon two years before at ole Oduma’s cattle camp, eight warriors arrived, armed with spears. “We have killed a white man,” they said. Peering through the stockade wall of thorns, Kiberenge glimpsed a European’s severed head. The next morning, he saw the head had been rammed on to a stake, from which also hung a penis, testicles and a hand. The warriors boasted they had met Dicky on his pony near the springs and that Bari ole Oduma, brother of the wizard, was the first to throw a spear into his chest. The pony reared, the man fell and other warriors used their swords to chop him up. After hearing their story, the wizard anointed the youths with magical powder, blew a blast on a shofar kudu horn and cast spells to protect them from arrest. Then he ordered the grisly remains should be returned to the crime scene.

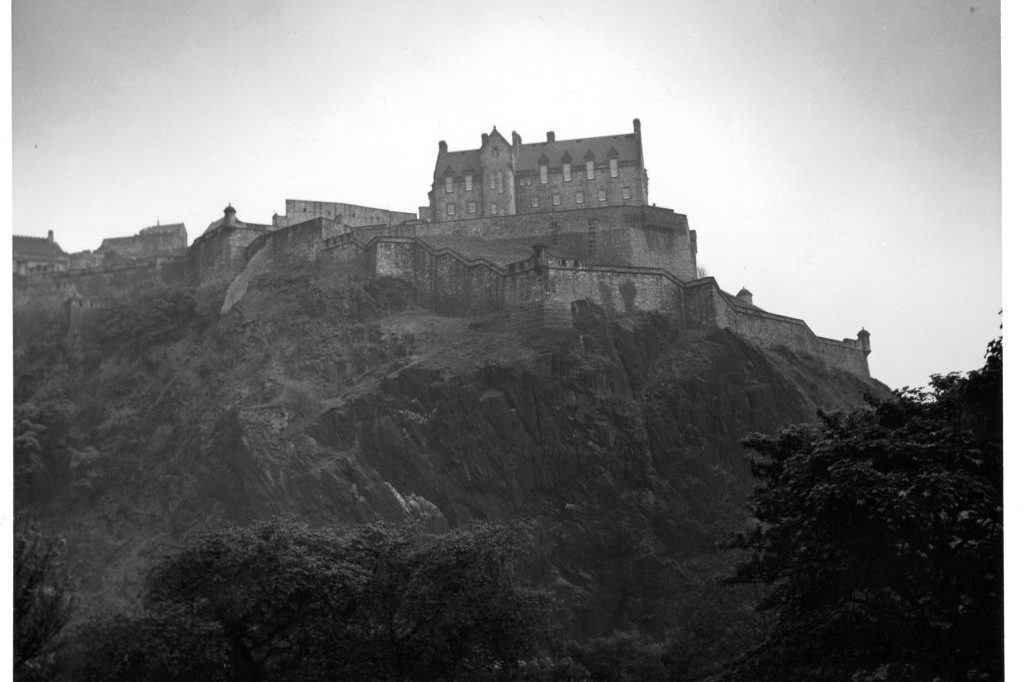

On November 27, 1934, ole Oduma and five warriors were finally brought to trial in the Rift Valley town of Nakuru. The laibon, now a popular resistance hero, said he was no wizard and only treated sick cattle and children. He denied all charges and when told to identify the other accused, he asked permission to look at them closely. “Those present in the court waited expectantly as he walked slowly to the box in which the Samburu stood and scrutinized them one by one with great care.” He said he knew them and reading the old newspaper reports convinced me the laibon was silently warning them to keep their mouths shut.

In a poorly handled trial sifting cold evidence all the accused were acquitted, causing uproar. Questions were asked in Westminster, but nothing happened. What the Samburu saw was British weakness rather than justice and they were embittered by the collective fines of hundreds of cattle as blood money to pay for the Kiliako warriors’ washing of the spears. Warriors were banned from carrying weapons, but from then until the present day our district has remained quite lawless — and these days warriors defiantly carry assault rifles as well as their spears.

At this point, Chief Panta said his own father was among the warriors who ambushed Dicky that day, claiming his spear hit the man and — like a scene out of Beowulf — the javelin shaft “shuddered” as it cleaved flesh and struck bone. “He’s still alive. Come and meet him,” he offered. A week later I took him up on his invitation, but when I reached Panta’s home I was told the old man had died the previous day.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2022 World edition.