I am part of an informal reading group with a few friends and colleagues. At the moment, we are reading Herodotus’s Histories (or “Inquiries,” as he might have said had he been writing in English). It’s lots of fun, in part because it is also an excuse to conduct a little wine appreciation class, but also because that old denizen of Halicarnassus — Herodotus lived from around 484 to 425 bc — was possessed of such high-octane and companionable curiosity about the world: what happened when and to whom and with what result. He wanted to know; moreover, he wanted you to know.

Herodotus is most famously a major source of our knowledge of the Persian Wars and such signal moments as the Battle of Marathon (490 bc), Thermopylae (480) and Salamis (also 480). He begins much earlier, though, with the exploits of such notable figures as Croesus, Gyges and Cyrus the Great. In Book Two, he travels to Egypt, where Cyrus’s heirs staked a claim, and he is full of fetching details, alternately factual and fanciful, about life around the Nile. His description of drinking parties among wealthy Egyptians, I fear, is entirely accurate:

They always follow the end of their dinner by having a man carry around a corpse made of wood inside coffin. The wooden corpse is crafted so as to be most realistic, both in the way it is painted and in the way it is carved, and it measures altogether one to three feet in length. As the man displays it before each of the guests, he says, “Look at this as you drink and enjoy yourself, for you will be like this when you are dead.”

Herodotus tells his readers that the Egyptians “remain faithful to their ancestral customs and add nothing new.” Our little band is not so unwavering. We skip the memento mori wheeze and concentrate first on food for thought while also not neglecting the other sort of food, which generally revolves around bread, olives, various cheeses and such delicacies as speck, prosciutto and mortadella.

All of that, of course, is by way of propaedeutic or excuse for some appropriate wine, which means something modestly priced but both food-friendly and sufficiently winsome to be enjoyed on its own. When our comestibles have a largely Italian stamp, we tend to pick a couple of Italian wines as accompaniments — though, to be perfectly honest, the question of which is the melody and which is the accompaniment is often lost in the course of our deliberations.

One white that has given pleasure is the Marchesi di Barolo 2018 from the Gavi region of Piedmont. I think Gavi is home to some of the best Italian white wine. They are made exclusively from the Cortese grape, a varietal that dates back to the seventeenth century. It is sturdy rather than elegant, robust and of sufficient acidity to stand up smartly to our smörgåsbord: more Honoria Glossop than Madeline Bassett, if I may employ an analogy from the corpus of The Master. This is not to deny, I hasten to add, that it lacks charm or a certain austere succulence. You can find it around for about $20 to $25 and you won’t need Herodotus entertaining you to enjoy it.

I can say the same for a reliable red that we found from the same region, the Monte Degli Angeli Barolo. We had the 2017 vintage of this noble Nebbiolo, and it was just the ticket. Plenty of agreeable fruit with no fussiness or pretension. It was not particularly long in the mouth, but what it lacked in length and finesse it made up for in frankness and immediacy. It’s the kind of wine that reminds you that delayed gratification can be overrated, and at around $25 a bottle it is ideal for your next encounter, literary or not as the case may be.

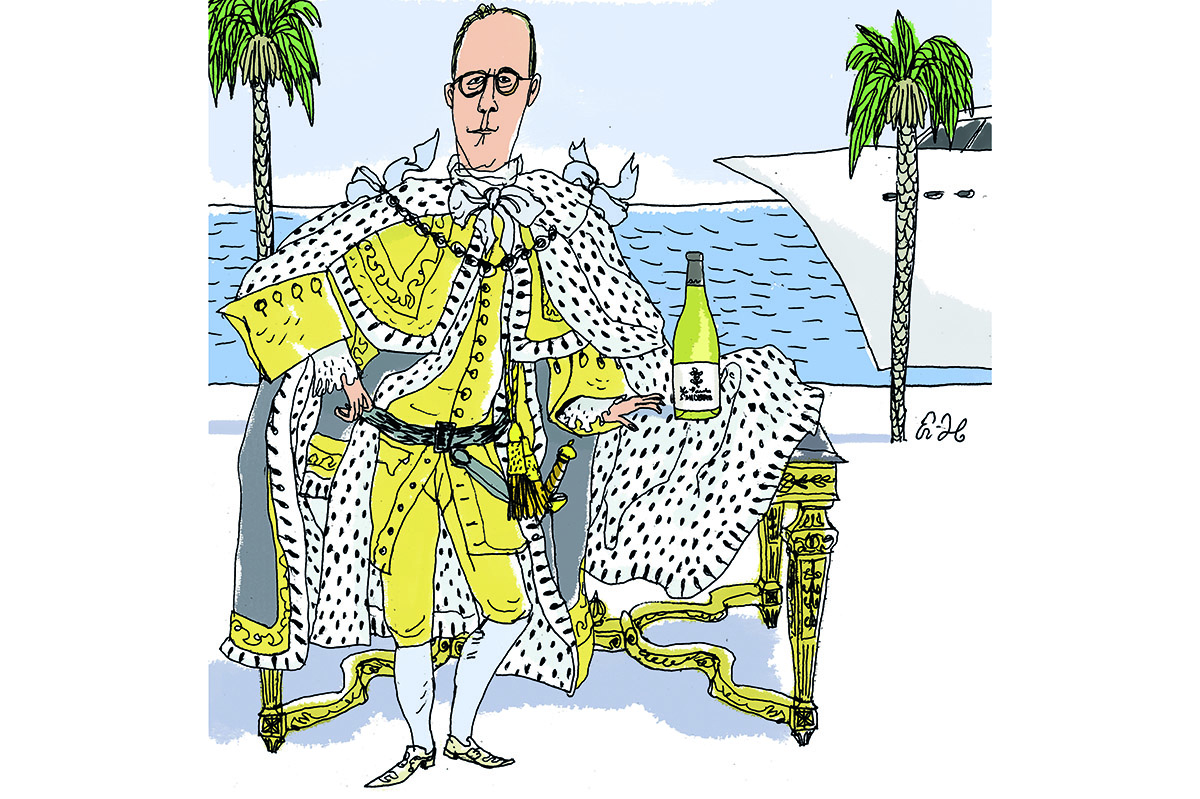

I want to end this column by mentioning a new discovery: Ulysse Collin, a Champagne from Olivier Collin. He makes five Champagnes from small parcels in and around his village of Congy. I have had only one, the 2015 Les Pierrièrres (the others are Les Roises, Les Enfers, and two called Les Maillons, one of which is a rosé). It was spectacular. You might say, “Well, for about $200 a bottle, it should be.” You would be right about that. It is a sad truth, however, that one can easily spend that much money and be disappointed. I was not disappointed with my first bottle of Ulysse Collin and I hope to have plenty of opportunity this season to test it again.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2022 World edition.