In the language of the Mapuche people of Patagonia, futa (I’m told) means “river” and leufú means “big.” So Spanish-speaking Chile could have called it the Rio Grande but instead have kept the indigenous name, Futaleufú, for this sinuous, deep, swift-flowing river, hurling its clear turquoise waters at the black basalt that flanks its roaring gorges. That this is one of the finest white-water rafting and kayaking rivers in the world is uncontested. And the river has given its name to the small town nestling beneath snowy Andean peaks and glaciers, past which it flows.

Before crossing the border into Argentina on a dirt road, six miles upriver, I spent a day in Futaleufú last week. We’d come far by bus from the south in Chilean Patagonia, and were on our way home to England via Buenos Aires a thousand miles north. My partner and our two companions had hired horses and cantered off up the hillsides and into the magical forest of southern beech cladding the lower slopes of the Andes. I don’t ride, so they left me at the bank to change money. And I was happy to be abandoned for a day.

Traveling, as we’d been doing for ten days, shows you much, and fast. Jungles, mountain passes, small towns, waterfalls, gorges thick with greenery, had slid past our steamed-up bus windows, and every so often we’d stop for a break; but never long enough to adjust to where we were. A hoot on the bus’s horn and we’d pile back in.

In a lifetime of traveling, I’ve found that you don’t begin to know a place until you’re stuck there with nothing to do. Only then does the bustle and tension of travel, the absorption in where you’re going and where you’ve come from, begin to fall away. Then you start to take things in. I was beached and in no hurry — luckily, because it became apparent that though I was fourth in the bank’s morning line, it was not moving. So I sat down and began to look around me, and get a sense of where I was.

Like the Hotel California, you could check in at the national bank but (it seemed) never leave. Chileans are friendly souls, straightforward in manner. Each arriving customer would pass through the swing door, stop, survey the scene, and take stock of the other customers. Then they would greet every-one they knew with a handshake. The sole stranger, I would receive a pat on the shoulder. You did not settle before acknowledging the others — mainly through touching.

Chileans are not a notably handsome people, rather stubby, often stout, with short legs and necks, and skin colors and physiognomy that betray a streak of the indigenous peoples Spain found there, and mostly killed. The ghost of lost tribes lives on in the mixed blood of so many Chileans; and the story of the systematic murder of entire cultures in Patagonia is unutterably sad, one of the great crimes of history. The intention being to hunt a race down like animals into extinction, it was a kind of holocaust. Irritated though I can be by the idiocies of woke “decolonization” of history, I do believe there’s a place for shame at what our ancestors did.

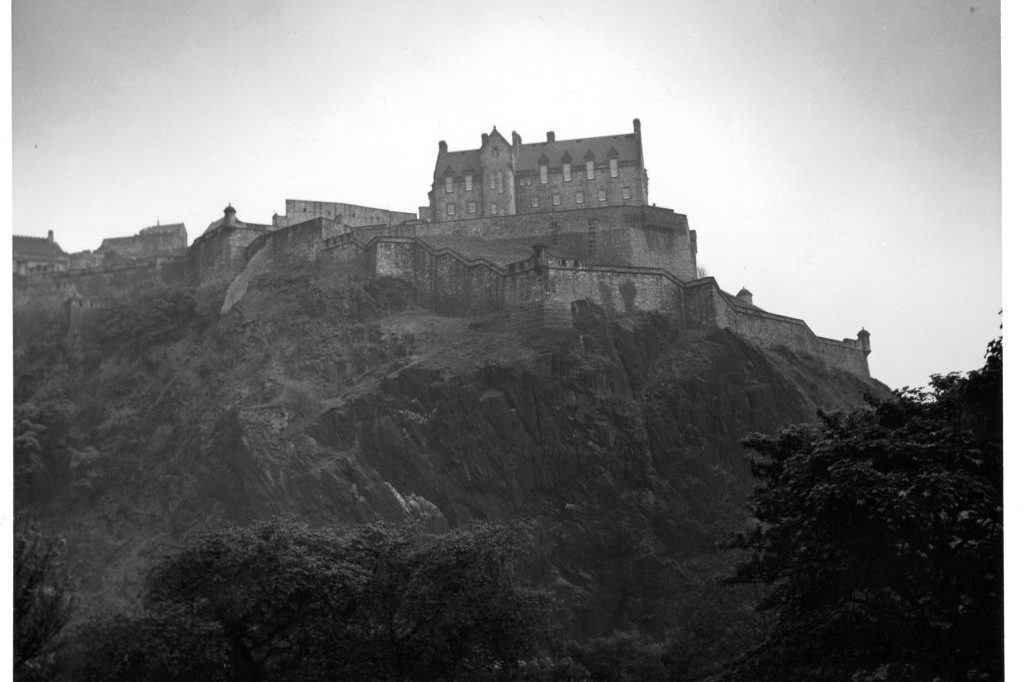

Finally I reached the counter, changed dollars, and walked out into the town square. It was a sunny morning. So I just spent the day walking around. Futaleufú has become a pleasant and self-respecting little town, a wide scattering of wooden homesteads whose busy tourist trade is built upon the river’s worldwide white-water reputation. But the tourist season was over, and all was quiet. I walked over to an outdoor photographic exhibition of this community’s history, told through fading black-and-white photos of families, weddings, funerals, workaday activities, and what in the last century had passed for events.

Looking into the eyes of this town’s long-dead forefathers, I saw only grim adversity. Until well past the middle of the twentieth century, life here had been anything but idyllic. These were pioneers who never struck gold, scratching a living from livestock farming in a place so inaccessible — far from the Atlantic and blocked from the Pacific by the Andes — that beef and wool struggled to reach their markets. A photograph of the arrival along mountain tracks of the first automobile, in 1950, showed the only schoolteacher and her family greeting the American Jeep; likewise the landing of the first Dakota DC3 at the airstrip the townspeople had built.

They dressed up for occasions, these people, the men in collar and tie; but you could see that most were very poor. A photo from 1930 of four young men, musicians with a guitar, shows baggy trousers, sombreros and berets in dire need of a wash. In another, sombre, gaunt faces and shabby children gather around the coffin of (I translate) “the Mama of Don Sabino Cortéz.” She isn’t named.

But it was the backdrops to these images that astonished me. Ravaged. This peasant community had created a wasteland around themselves. All the native trees were dead, gaunt or felled right up the slopes that rose around them. This landscape had been smashed for livestock. To sustain a few hundred poor European immigrants, a precious, fragile environment and its wildlife — pumas, deer, condors and millions of trees — had been plundered. And nobody — nobody but a few environmental prophets in Argentina and Chile — had cared.

Those prophets’ successors, though, have carried forward their vision. A national park of lakes and forest now spreads north from the Argentinian border, mirrored nearby in Chile right down to the Pacific. Upwards from Futaleufú the slopes are clothed in dense dark green forest, all regenerated in fifty years. The pumas are back. Kayakers and rafters support better lives for the towns-people than marginal agriculture ever did.

Perverse as it may seem, roads and tourists have taken pressure off this landscape. We humans may have tightened our grip, but with control can come enlightenment. Sometimes things can get better. But only we can get it right.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.