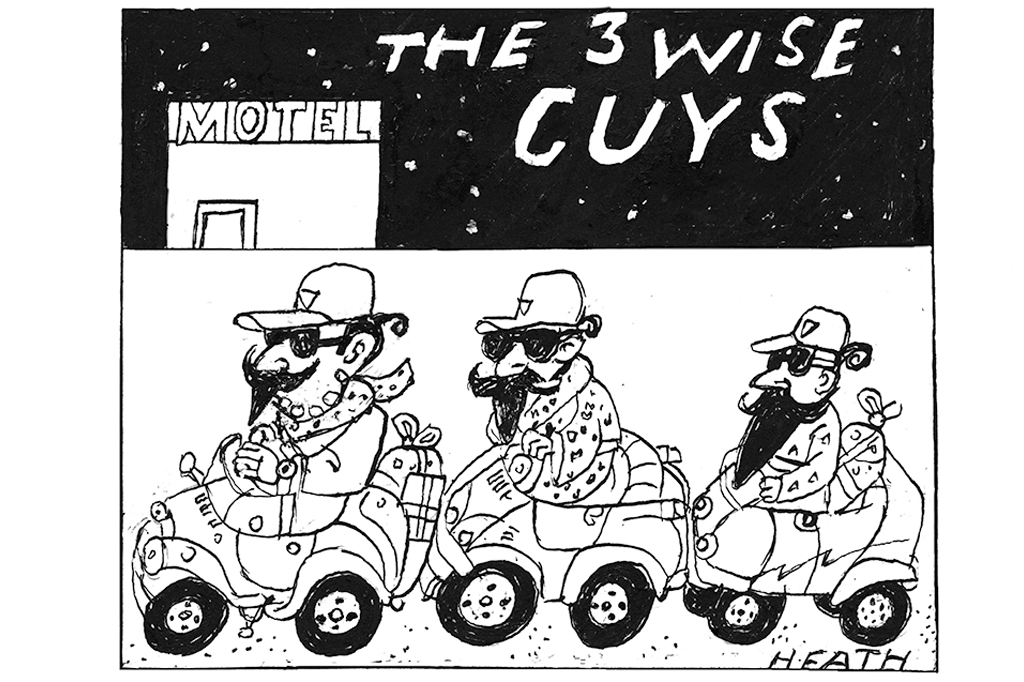

This week we get to Epiphany, the Twelfth Day of Christmas, when the wise men finally make it to baby Jesus in Bethlehem. Properly, the feast starts the night before, so Twelfth Night is the evening of January 5, which in some parts of Europe is the climax of the Christmas season.

And, as with every good thing, it’s an occasion for cake — king cake to be precise. There are several variants from different parts of Europe. The best-known here is the galette des rois, which features in French patisseries: a lovely almond paste encased in puff pastry and, in shops, surmounted with a cardboard golden crown for whoever gets the bean on the inside. I make it in a version by Joël Robuchon with slices of pineapple. Delicious.

In Spain, where Epiphany is a big deal, the cake is made of a soft yeasted dough and shaped into an oval, decorated with candied or crystalized fruit, with a bean or figurine of baby Jesus on the inside.

But it’s the English variant — known as Twelfth cake — that’s worth considering. It started as a rich yeasted fruit dough cake in the sixteenth century and in Samuel Pepys’s day it was an essential element of the Twelfth Night celebrations. In one half would be hidden a dried bean, in the other a dried pea, and whichever man got the bean and whichever lady the pea were king and queen of the night, a reminder of the old feast of Misrule that used to characterize the medieval festivities. For the feast of 1659-60 Pepys wrote: “To my cousin Stradwick, where, after a good supper, there being there my father, mother, brothers, and sister, my cousin Scott and his wife, Mr. Drawwater and his wife, and her brother, Mr. Stradwick, we had a brave cake brought us, and in the choosing, Pall was Queen and Mr. Stradwick was King.”

Some Twelfth cakes were enormous, an opportunity for a display of competitive sugar craft by confectioners. Pen Vogler, author of Dinner with Dickens, recalls that the author would joke that the cake sent by his son’s godmother every year weighed ninety pounds. The version of Queen Victoria’s Twelfth cake, replicated in the Illustrated London News of 1849, was “thirty inches across, gilded around its bowed sides, and displayed an elegant sugar-paste party enjoying a detailed sugar-paste picnic.”

The recipe had changed — it was no longer raised by yeast but by a good deal of elbow work on the part of the cook, which, in the quantities called for at the time, must have been considerable. It was pretty much a spiced, citron-rich version of Christmas cake. As Vogler observes: “By the early nineteenth century, it was an opportunity for family theatrics and fun that hugely appealed to Dickens; he had happy memories of Twelfth cakes and dancing at his school.”

The fate of the Twelfth cake reflects sadly on the present condition of the feast. Victorian commercial interests disagreed with twelve whole days given to frivolity: the reduction of the twelve days of Christmas to three measly bank holidays was one result, the other was the migration of Twelfth cake to Christmas Day, when no one has space for it. So here’s the plan. Forget stupid Veganuary and puritan Dry January. Bring back the Twelfth cake and ale!

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.