London

The launch party for my book has gotten sensational reviews. “Party of the year!” said one friend. “Simply brilliant!” said another. A hack from the Times declared, “It was like an old-fashioned Fleet Street Party” — by which he meant everyone was drunk, dancing and misbehaving. Unfortunately, my book has not gotten sensational reviews. It’s gotten no reviews — at least from the national press. This is a cause for worry.

Or so my publisher Todd Swift of Eyewear Publishing thinks. The day after the party he calls me. I’m still buzzing with my party reviews; he’s buzzing with panic. Todd tells me that no reviews mean we can’t get my book into the major bookshops! I’d hate to see your great book die, he says.

I tell Todd not to worry; people can always buy my book on Amazon and it’s then I catch a whiff of my own hypocrisy.

Todd is a small independent publisher. Indie publishers are like indie bands — wonderfully creative and woefully uncommercial. But then they’re in the book business for love, not money. When I first met Todd I thought that, like me, he was a neurotic American Jew. Later, I discovered he was in fact a neurotic Canadian Catholic. Most Canadians — and Catholics — can’t do neurosis like we American Jews. Somehow though, Todd can, and so we get on perfectly.

The main reason my book is in trouble is that the English actor Richard E. Grant’s book on the death of his wife from cancer has come out at the same time as my book on the suicide of my son. His is an instant bestseller; mine is on the brink of being an instant flop.

To be fair, they’re very different books, both in style and content. My book is insightful, intelligent, beautifully written, funny and moving. Grant’s book is… moving. But book editors don’t want to give review pages to another book on loss when they’ve already covered Grant’s.

Oscar-nominee Grant is not only famous, his book is also packed with guest appearances by his famous friends. Charles — now the King of England — pops around with a bag of mangoes. Nigella sends dinner over by taxi and there’s the call of condolence from Elton John. How can I compete with that?

When my son died in 2015, I was told to expect an endless stream of casseroles, baked cakes, tearstained letters, sympathy sex and book deals. And what did I get? Bupkis. Instead of having a nice casserole from Nigella, I lived on pot noodles. When a friend of mine’s wife died, he couldn’t get out the front door for casseroles left in his driveway — it was the food equivalent of those floral tributes that followed the death of Princess Diana. But then he was famous too.

When I tell people that my book is, in parts, really funny, they give me a disapproving look. People think that tragedy demands constant solemnity and so the appearance of humor is considered in bad taste. Loss and grief have their funny side — though to laugh while in mourning feels like we’re betraying our loved one. But as George Bernard Shaw put it, “Life doesn’t cease to be funny when someone dies any more than it ceases to be serious when people laugh.”

The night after my book party I went to a party full of artists who were part of the annual London Frieze exhibition, and I couldn’t help but notice the difference between artists and writers at play. Over the years I’ve been to dozens of art parties and I’ve never once had fun. Why are parties full of artists so dull? Don’t get me wrong, I have artist friends who are great company — but when artists gather en masse something happens; they go into art-bore mode.

Artists don’t know how to socially engage with people who aren’t artists — they don’t know how to be charming or funny, or the basics of making conversation. And they’re never sexy! The problem is that artists take themselves more seriously than any other creative tribe — yes, even more seriously than literary novelists! They imagine that because Art is important, they must be important too.

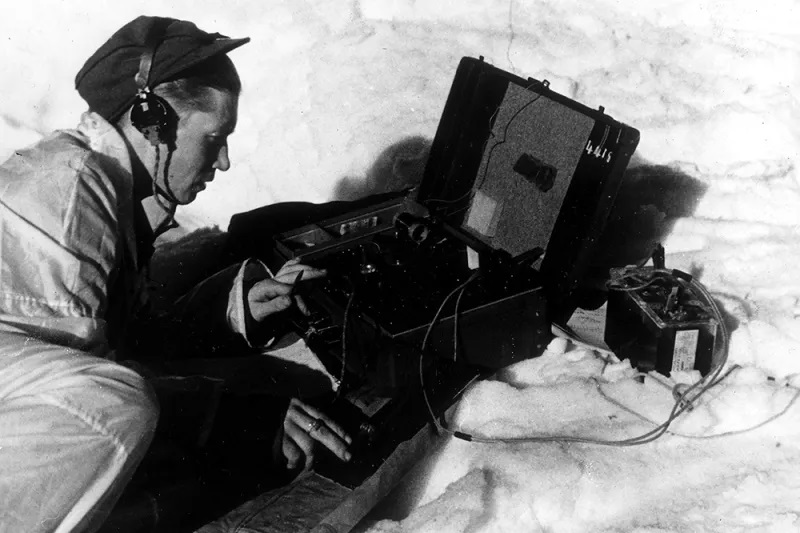

Say what you want about us old journos — we’re rude, reckless, feckless, untrustworthy, drunk, full of spite and envy — but we don’t take ourselves seriously. (We have too much self-loathing for that.) And we try to be funny. Artists have no sense of humor; no ability to send themselves up. The last time an artist cracked a joke was in 1917 when Marcel Duchamp put a urinal in an exhibition.

Art people just want to talk about their art. There used to be a popular t-shirt in the 80s that read: Fuck Art Let’s Dance — now it’s more a case of Fuck Dance Let’s Talk Art.

Oh. I forgot to mention my friend who had planned to meet Jordan Peterson instead of my party actually turned up. I was so pleased and told him he was a true friend. “That’s okay,” he said, “The Peterson event had been canceled. I had nothing else to do.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2022 World edition.