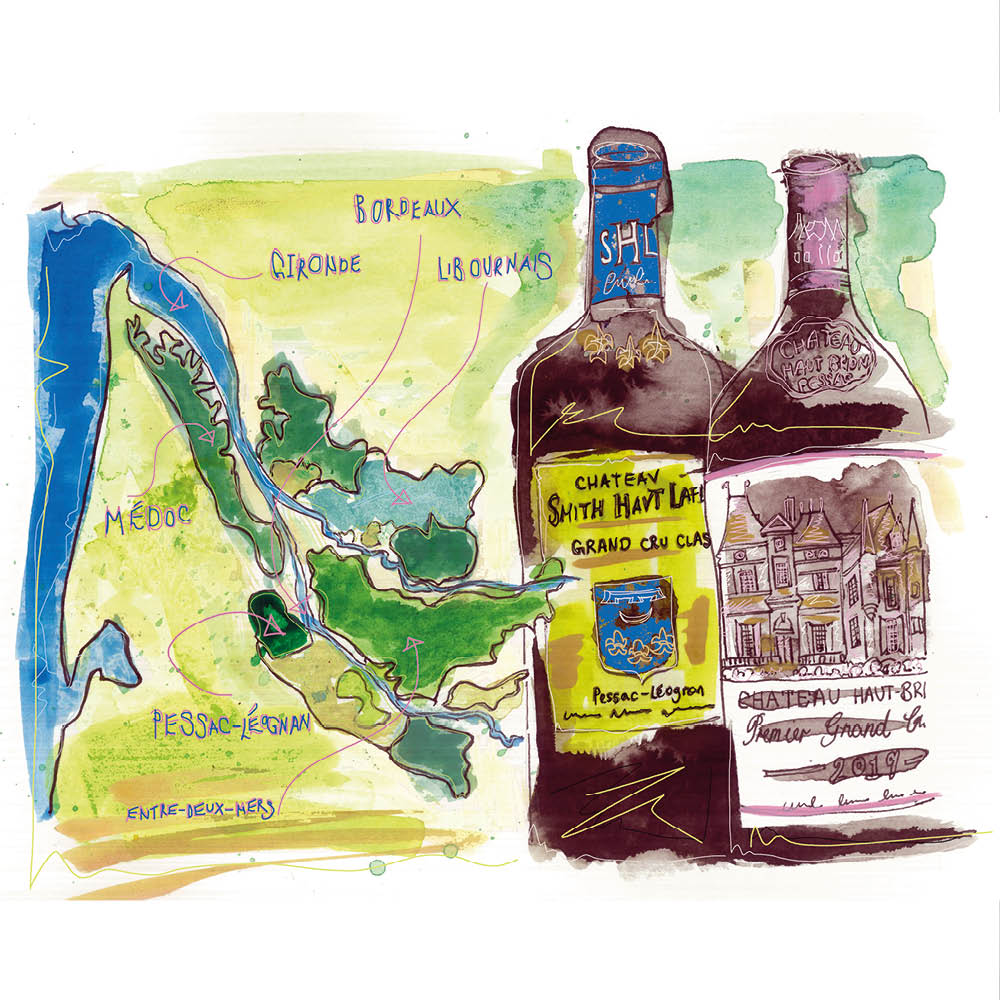

When someone says “Bordeaux wine” most of us think first of wines from the Médoc, home of Pauillac, Saint-Julien, Saint-Estèphe, Margaux and other celebrated names. For some reason — marketing prowess, perhaps — the great region of Pessac-Léognan, directly to the south in Graves, cheek by jowl with the town of Bordeaux, comes up mostly as an afterthought.

This is both odd and regrettable.

It is odd because, as a matter of history, Pessac-Léognan takes precedence. I suppose the story begins with the marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine to the future Henry II in 1152. Eleanor brought vast lands from that region of France to the marriage, so there is a sense in which the French wines the English have loved since the Middle Ages were originally English. And early on, they came from Pessac-Léognan. The vineyard called Pape Clément, a Cabernet-Merlot blend (40 percent Merlot), was planted in 1300, making it by some measure the oldest vineyard in the whole region. (At that time, as one writer observed, much of the Médoc was still a swamp.) Bertrand de Goth, then archbishop of Bordeaux, was given the vineyard by his brother Berald. He took the name Clément V when he ascended to the papacy in 1306 and gave the name to the vineyard, passing it along to the new archbishop of Bordeaux so he himself could attend to moving the papacy to Avignon in 1309.

What makes the relative neglect of Pessac-Léognan regrettable as well as odd is the high quality of the wines from the region. They should be more widely known. It was here, as Hugh Johnson observes in his classic World Atlas of Wine, that “the whole concept of fine red Bordeaux was launched.”

There is only one wine from Pessac designated a “first growth” in the 1855 Bordeaux specification. It is Château Haut-Brion, an extraordinary wine from the north of Pessac that features an equally extraordinary price. The 2019 vintage is nearly $600. A very close second — designated a grand cru in the later 1959 scheme in Graves — is Pape Clément, more or less due west of Haut-Brion. I shared a bottle of the 2019 vintage — about $130 — with some friends recently when we decided to make a little virtual trip through Pessac-Léognan. It was superb — dark, flinty, elegant but strong and lingering. It was also young — not too young, exactly, for it was delectable — but you could tell that this was a wine that would age well, gaining in fruit and depth and complexity.

We serious thinkers sampled several other excellent wines from the region that day. The Pape Clément was probably the crown jewel, but all were gems in the diadem. We started with a beguiling white, the 2021 Le Petit Smith Haut Lafitte. Note the “Smith.” The vineyard, on a gravelly plateau called “Lafitte,” dates from the fourteenth century. It was acquired in the eighteenth by a Scotsman called George Smith, who built the Château and added “Smith” to the lieu-dit. Located in the south, in the commune of Martillac, Haut Smith is one of the dozen most celebrated vineyards in Pessac-Léognan. The white is a blend of 80 percent Sauvignon Blanc and (not surprising since we are approaching Barsac and Sauternes) 20 percent Sémillon, which softens and gives a certain roundness to the tartness of the Sauvignon Blanc. A wonderful, refreshing wine which you can get for about $45.

The red, Smith Haut Lafitte without the “Petit,” is a robust blend of 60 percent Cabernet Sauvignon, 30 percent Merlot and dollops of Cabernet Franc and Petit Verdot. We had the 2014, another solid year. The vintage charts say “hold” but we found it full, ripe and ready. You should be able to find it for under $100.

Two more. Château Bardins, which dates from the nineteenth century, is in the commune of Cadaujac, about midway between Haut-Brion and Haut Smith. We had the 2018, a Merlot-heavy (65 percent) blend that also features Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc. It was young, taut and full of promise. You can tell that the fruit will continue to sprout and develop as the wine ages. At $45, it is a steal, especially if you can lay it down for a while.

Our last wine was a star, equal or almost equal to the Pape Clément. There are a bunch of wineries clustered around Château Haut-Brion that feature the name, some of the luster and various historical connections with the great first growth. One of the best is Château Les Carmes Haut-Brion, which is located just to the north of Château Haut-Brion. The 2019 was 50 percent Cabernet Franc, 34 percent Cabernet Sauvignon and 16 percent Merlot. Again, it is a young wine that will continue to improve for forty years or longer. But it was gorgeous now, tight but fruit-forward, with prominent but elegantly trellised tannins. A bottle will set you back about $140 but since you will have bought a case you can look forward to drinking it for many years to come.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply