The new prime minister of France, Gabriel Attal, has promised to “take care” of Oradour-sur-Glane. The village, in west-central France, was the scene on June 10, 1944, of an infamous Nazi massacre of 643 men, women and children, shot or locked in the local church and burned alive. Only six villagers escaped to tell the tale; the last of them died in 2023.

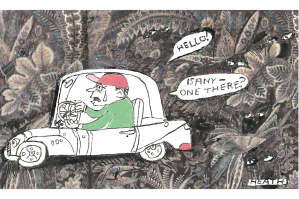

For years Oradour-sur-Glane has been a site where schoolchildren were taken to learn about what France endured during World War Two. Recently the abandoned village has become overgrown with vegetation, but with the eightieth anniversary this summer, the descendants of the victims are making sure they are not forgotten.

In 1988, as a stringer for the Wall Street Journal in Brussels, I wrote a review of a newly published book: Oradour: Massacre and After, by Robin Mackness. The book became an instant bestseller. It uncovered a part of World War Two history that many French wished would be forgotten, as it shone a light on the dark story of those who had been sympathetic to the Vichy government.

I knew Mackness and his wife, Liz — English expats who lived near us in Lausanne, Switzerland. They were due for dinner one night in 1982 when I received a call from Liz, saying that Robin had been arrested in France.

At that point I was the Swiss correspondent for the International Herald Tribune, and Robin contacted me from the French prison where he was serving a twenty-one-month sentence for attempting to smuggle twenty kilos of gold ingots into Switzerland. He was also fined 8 million French francs. He was writing a book about his trial and wanted my input on how to find a publisher. The gold bars were, according to Mackness, the savings, melted down into gold bars, found under the mattresses and other hiding places of the Oradour villagers before they were exterminated. The Nazis knew about the town’s gold from Vichy collaborators.

Mackness had established a successful investment company in Lausanne. He claimed that in 1982 he was presented with a deal that involved making him a director of a Swiss bank if he brought twenty kilos of gold to the bank from France. The ingots belonged (he claimed) to a French client of the bank and were to be moved from Toulouse to Évian. The gold would then be smuggled into Switzerland

Mackness agreed to carry out the mission, believing his part in it would not be illegal. He was fascinated by the element of adventure (he once asked me and a few other skiing friends to do la Haute Route from Chamonix to Zermatt, a very difficult itinerary that should only be attempted by expert skiers — which none of us were) and was eager to break into the elite circle of Swiss banking. Maybe, a mutual friend opined at the time, Robin was thinking the gold could be smuggled in knapsacks over the Alps.

What ensued turned out not only to be a nightmare for the Macknesses but eventually a gripping tale of high finance and an indictment of President François Mitterrand and his Socialist government. More importantly, a new explanation for the decades-old mystery of the Nazi massacre emerged in the course of the strange odyssey.

The book turned out to be two tales in one: Mackness’s personal saga and the story of an SS rampage near the end of the war in a small French town.

The modern part of the Oradour tale started when Mackness got involved in the transfer of the ingots out of France. He says in the book that he insisted on knowing the origins of the gold from “Raoul,” the client in Toulouse, before taking the gold to Évian. Raoul, said Mackness, told him the gold was from a half-ton cache he’d captured personally after his group of French resistance fighters ambushed a small SS convoy near Toulouse in 1944. Credence to this was lent by the fact that five of the ingots were stamped “RB” — the insignia of the Nazi Reichbank.

Satisfied with Raoul’s explanation, Mackness hid the twenty ingots in his BMW and headed for Évian. Outside of Lyon, he was stopped by customs men and his car was searched. As the ingots were pulled out from under the front seat, Mackness realized there’d been a tip-off and made a dash for it. Bullets flew and he was finally caught.

As Mackness told it, he was held for four days incommunicado by French customs, tortured by a sadistic, leftist official, who put him in handcuffs attached to a hot radiator and tried by a young, leftist judge in jeans. He was fined and thrown into prison for twenty-one months. I accompanied Liz Mackness to the jail, as did other friends. Under French law (based on the Napoleonic Code, which states that if one is associated with a criminal, one can be prosecuted as an accessory), Liz could have been jailed, assuming she knew her husband’s business dealings. She was luckily never retained, as the Macknesses had two small children.

Mackness’s crime was to have been caught with the gold in one of France’s zones franches, duty-free zones within twenty-five kilometers of a port of entry and in which large quantities of goods in one’s possession are presumed to be for export. The crime was compounded in the eyes of French customs by his refusing to divulge the source of the bullion. This, they felt, cut off the possibility of taxing more gold from the same source.

The book’s parallel narrative tells the story of the Oradour massacre. Historians have long pondered what its impetus was: reprisal for the Allied invasion, or for something else, as Raoul’s story suggested? After his encounter with Raoul and almost two years in a French prison researching his story, Mackness was sure he had the key to the puzzle; the gold he was given in Toulouse was indeed some Nazis had collected during the occupation. The massacre of Oradour was carried out to find the treasure, stolen during the Resistance ambush.

Many questions, however, remained unanswered. One is why a Swiss bank would want to jeopardize its courier by sending him into a zone franche. Another is how to confirm the story beyond the testimony of “Raoul,” on whose word the book depends and whose death in 1982 conveniently closed an important source of information. The third is what the alleged behavior of French customs — odd at best, brutal at worst — says about French law.

On the light side, Mackness was imprisoned in Annecy in the same prison as a Michelin-starred chef and wrote that he’d never eaten so well for such a long period of time. The chef had been convicted of murdering his wife, and when the prison officials found out about his métier, the chef was asked to take over the prison kitchen.

So far, no further evidence has emerged to contradict Robin Mackness’s hypothesis: historian M.R.D. Foot wrote in the Sunday Times of London the week the book was published that the gold explanation “makes sense.” For the history the book delivers about what happened to the citizens of Oradour-sur-Glane alone, it is valuable. The Macron government is right to keep the site of the village available for teaching French children some of its history.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply