If ever I write a sex farce — the demand so far has been muted — I need only head east 150 miles and detour back 150 years to the Oneida community, the utopian experiment in free love that thrived from 1848-80 before the colony’s unorthodox sexual arrangements led to its collapse — and, in a characteristically American turn of events, its road to riches.

Headquartered in a sprawling mansion house — open today to visitors of all carnal habits — Oneida was a cerebral nineteenth-century soap opera awash in high-minded American radicalism and directed by the brilliant and charismatic megalomaniac John Humphrey Noyes. As a Yale Divinity School student, Noyes had declared himself free from sin: a perfected Christian. This astounding heresy soon made him an ex-Yale Divinity School student.

Like many a young man with big dreams, Noyes married a girl whose family wealth compensated for her plainness. Her dowry enabled him to found the Oneida colony upon the precepts of Bible communism (all property was held in common), Christian Perfectionism (which released members from the obligation to obey every jot and tittle of the moral law), and — the teaching that made Oneida infamous — what Noyes called complex marriage.

Oneida attracted a mélange of accomplished young women, often of high station, idealistic young men, wandering mystics (some saintly, some touched) and a gaggle of eccentrics, lured perhaps by the promise of utopia but more likely by the prospect of bluestocking poontang. Though not classically handsome, the tall and slender Noyes radiated erotic holiness. One Oneidan wrote, “I went to his room and told him I could do one thing, and that was to submit myself to him and look for his spirit to enter into me and fill me… He is full of mercy and tenderness.”

Noyes was not reluctant to have his spirit enter his sister Oneidans. The door to his modest room was always open to those who wished to drop by for cards or coitus. To forestall a population explosion, and to save women from the pain of childbirth, Oneidans practiced — fitfully — “male continence,” or withdrawal. Noyes wrote at length upon the subject, though he still fathered thirteen children. (Sometimes —as Meat Loaf explained so histrionically in “Paradise by the Dashboard Light” — you slip up, in which case the offspring were raised communally.)

Sexual congress was voluntary; Oneidans were free to refuse propositions. A third party, usually an elder, would act as intermediary in prospective liaisons. The petitioner — typically male — would request conjugation; if the object of his desire were amenable, the adjudicator would decide yea or nay.

The young bucks grumbled about Noyes’s doctrine of “Ascending Fellowship,” which directed younger men to post-menopausal women and younger women to older men — most prominently John Humphrey Noyes, who seems to have taken a particular interest in these initiations. Harriet, his meal-ticket wife, was now but a “yoke-fellow.”

Lovers who developed feelings of, well, love for others were accused of harboring “the marriage spirit.” They were upbraided, often scaldingly, in the “mutual criticism” sessions to which Oneidans submitted in lieu of formal rules and regulations. Noyes exempted himself from mutual criticism — unless, he said, Jesus and Saint Paul were to show up and find his faults.

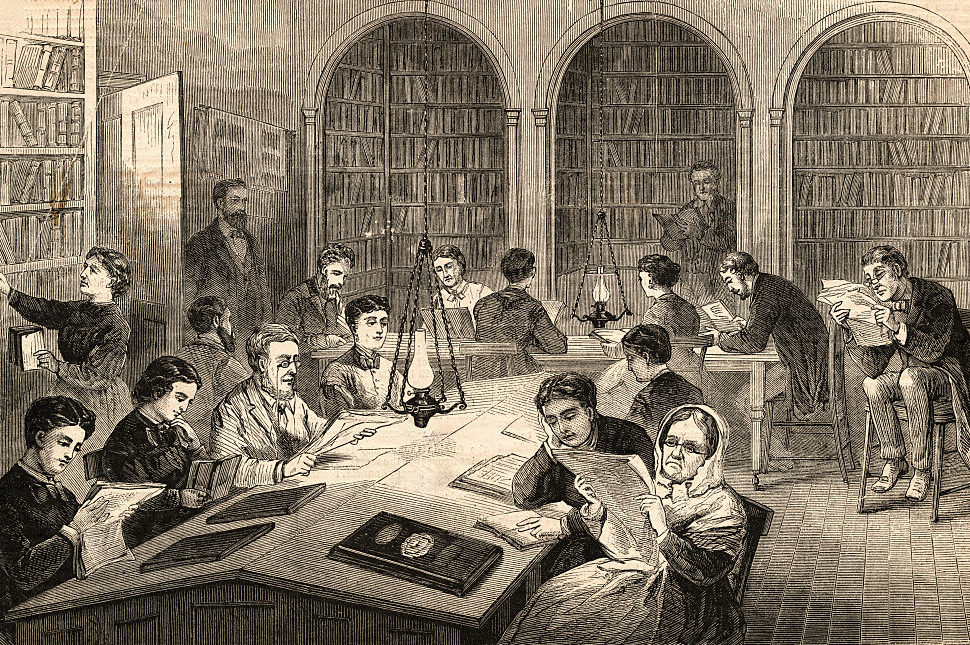

Snickering aside, one must credit the Oneidans, who numbered 300 at their peak, for possessing that nineteenth-century American urge for self-improvement. They studied Greek, astronomy, grammar, algebra and music. They played croquet and baseball; they put on plays and concerts; they fled to the fields to pick strawberries or enjoy the spring sunshine. There was a genuine joy at Oneida that was absent in most ostensibly utopian colonies, yet there were poisonous jealousies, rancorous fights and, underlying all, the complications and heartbreaks and absurdities inherent in complex marriage.

In 1879, despairing of the selfishness of the new generation, Noyes announced the end of complex marriage. A brief sexual free-for-all ensued, followed by a splurge of conventional marriages. Noyes hightailed it to Niagara Falls, Canada, just ahead of the authorities, who had been spurred on by Presbyterian ministers insisting the heresiarch be arrested for sexual irregularities.

A year later, this Upstate New York experiment in Bible communism and free-ish love broke up — or, rather, it transmuted into a joint-stock corporation called the Oneida Community, Limited, which became the nation’s leading manufacturer of flatware.

The weird old America’s most outrageous and successful experiment in communism ended — in an orgy of moneymaking.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2023 World edition.