These pages recently carried a lament for the little French restaurant, and the loss from the cities they once graced of a certain element of gentility and, yes, class. On the same subject, let us consider another era when class was valued more highly, and which produced the classiest, and the grandest, French restaurant of all. This requires a journey.

In July 1936, a Chicago family, relations of mine, embarked on an unrushed two-month European vacation. A meticulous Thos. Cook & Son-Wagons-Lits, Inc. itinerary routed them first to France, then Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Holland and finally to England. It was a thoroughly first-class affair. They stayed in top hotels (the sort with plenty of staff, service and en suite bathrooms), and they moved about the Continent by rail, steamer and chauffeured automobile. They sailed at a time when there were dozens of ships to choose from. They chose the best: the then-largest (83,000 tons; 1029 feet long), fastest (30-plus knots) and most elegant liner in the world. The French Line’s Normandie entered service in 1935, one year ahead of her great British rival, Cunard’s Queen Mary, and soon captured the Blue Riband for fastest North Atlantic crossing from Italy’s Rex. Among her many superlatives, none was more superlative than her First Class grande salle à manger — the biggest French restaurant in the world.

Normandie was the product of the final burst of liner-building for the lucrative North Atlantic trade, when great ships were still objects of intense national pride. It is some irony that the 1930s, that most distressed of peacetime decades until perhaps our own, should be remembered not only for economic depression, the rise of the dictators and the disgrace of appeasement but for the creation of some of the largest, most beautiful machines ever to come from the hand of man — Normandie, Queen Mary, Queen Elizabeth, Empress of Britain, Bremen, Europa, Nieuw Amsterdam, Rex. Many, including Normandie, would not survive the war. Those that did sailed on into obsolescence in the air age, their demise marking the end of a way of life at sea.

As a symbol of that way of life, no space on any other ship could compare with Normandie’s grand restaurant. Three hundred-five feet long and forty-six wide, it was the largest room afloat. Its hammered copper ceiling rose a full three decks above the floor. A great staircase at the forward end emphasized the long, thin grandeur of the space and evoked visions of Versailles or something off the Champs-Élysées. After modification following the first season, it seated 700, the full complement of First Class.

Never had one great room better conjured up a national essence. Nor could there have been any sharper contrast with her national competitor. As a perceptive passenger once put it to Normandie’s captain: “The Queen Mary is a grand Englishwoman in sportswear. The Normandie is a very gay French girl in evening dress.” Vive la différence.

Our Midwestern family readily soaked up this French atmosphere. They had lived in France in the Twenties, where the father had varied business interests, including in the perfume trade. Most of them were fluent French-speakers, and they would have reveled in reading the verso (French) side of the menu and suavely placing their orders to starchy waiters, en français. European travel even for wealthy Americans was still relatively rare ninety years ago, and these particular travelers, however sophisticated, regarded their trip as something of a special treat. The sensation sharpened every time they opened the menu. The menus from that voyage reside today in my study, works of art (prints of French warships from the age of sail, e.g., Le Dauphin Royal, 1752, which fought at Aboukir, adorned dinner versions; native costumes of Normandy, e.g., Paysanne des environs d’Avranches, at lunch) that bring a thrill, still.

Normandie was the ultimate French ship, and those menus catalogued French food. The line had produced a classy PR film of the maiden voyage, filled with handsome rich people luxuriating in life on board. It was narrated, naturally, in French. But even those with little ear for the tongue could not, as the camera panned guests in white-tie and long gowns being seated in the great restaurant, fail to pick out the phrase “la grande cuisine française.” It was spoken with a certain Gallic nonchalance. But of course: what else is there?

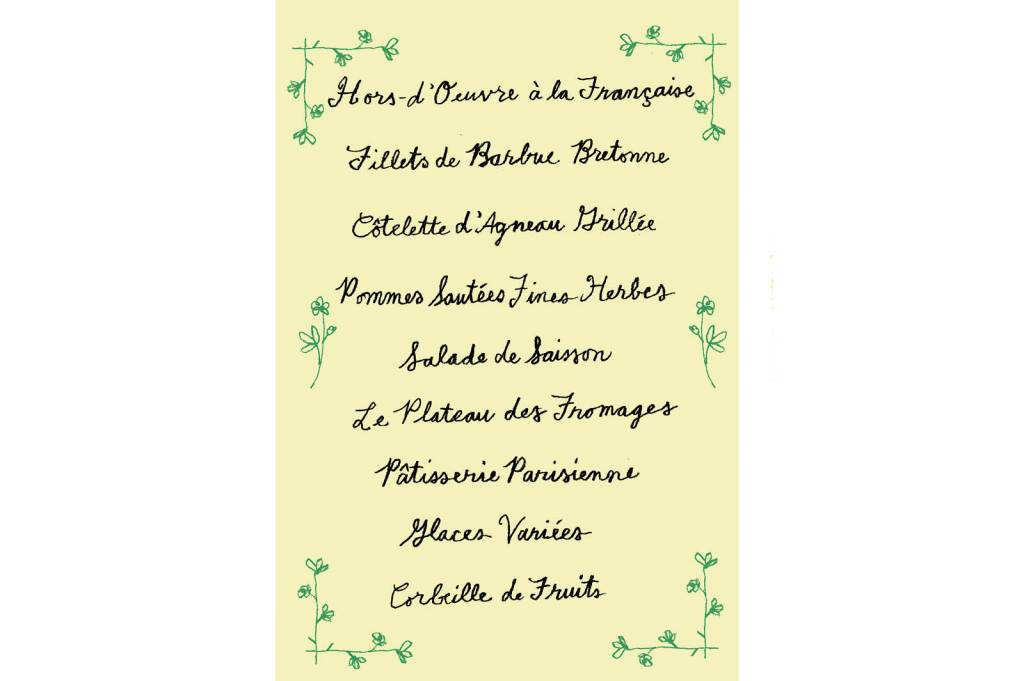

One ordered à la carte, as much or as little as the spirit moved. Prevailing prewar tastes were still, in this setting at least, unapologetically Lucullan. Menus changed daily, and their routinely listed seventy-plus dishes did not exhaust the chefs’ repertoire. Almost anything could be had. True gourmets could look with pleasure over seventeen categories of à la carte listings and construct their own one-of-a-kind repast. Those less keen, or perhaps a bit intimidated, could reliably resort to the “Menu Suggestion” of the day, highlighted in between French and English sides of the card, viz., for August 29, 1936:

And that was luncheon. Following a cigarette, a snooze and a turn (or ten) around the deck, it would be time for tea, then time to don evening dress, then to the Grand Salon or the Bar Américain for cocktails, then to the grande salle for the main event.

Dinner in First Class on Normandie was a multisensory experience. Cuisine, architecture and décor combined to achieve a sense of Gallic grandeur reminiscent of the days of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. It was not a copy, however — out was Bourbon high-baroque; in was modern machine-age deco — but you could be sure that the sauces and every other culinary creation of Normandie’s seventy-six chefs and 100 assistants more than measured up to the classical standard. The room was often compared to the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles (in fact it was longer by sixty feet), its backlit Lalique glass walls and parade of crystal jardinières bathing the three-deck high interior with the light of 135,000 candles. And on the monumental staircase each night was reenacted, à la Normandie, the established ritual of great French ships with ladies descending to dinner while formally dressed diners below gazed up with discriminating eye. Paris gowns by Lanvin and Chanel were not unusual or, in the case of our Chicagoans, the very best that Marshall Field’s had to offer.

Some critics would say that the dazzle of Normandie was simply too much, too luxe, and that the statelier atmosphere of the Queen Mary made for more comfortable surroundings. Perhaps so, but when it came to the kitchens, there was no contest: English hotel fare versus France’s finest. Pointe finale. The Mary soon enough snatched away the Blue Riband for speed, but passengers continued to book passage on Normandie for the food alone.

Let us contemplate, alas if only in our imagination, ordering dinner in seven courses off the card as the maître d’ actually presented it for Jeudi 27 Août 1936. With so much on offer diners learned to choose, which was not always easy. For hors-d’oeuvre, will it be Canapé Lucile or Homard Cocktail or Ananas Frais Rafraîchi au Kirsch? For potage, Consommé Froid Viveurs or Consommé Belle-Fermière or (naturellement) Soupe à l’Oignon? For poisson, Suprême de Barbue Waleska or Darnes de Brochet au Beurre Nantais? For entrée, Mignon de Charolais Masséna or Pigeons Rôtis Bardés or Baron d’Agneau à la Broche? Or perhaps a selection from the buffet froid: Longe de Veau à la Gelée Printanière or Langouste Mayonnaise or Terrine de Foie Gras Truffé de Strasbourg? To accompany all of this, vegetables and starches abounded. Salads always followed the mains and preceded the cheese. There I might choose Rouy-d’Or and Crème de Gruyère. Pâtisserie (choose Gâteau Savarin), entremet (choose Bavaroises Favorites), glaces (choose Bombe Hollandaise) and, en fin, fruits filled out what would have been a good two hours at least at table.

Relatively few ever savored such triumphs of la grande haute cuisine in this greatest French restaurant, and virtually all of them, including my relatives, are now passed from the scene. Normandie sailed for just four seasons before being cut off by the war, 139 crossings in all. In retrospect, her short life and shameful death only added to her brilliance. While being hastily converted to a troop ship in New York (she was to become the USS Lafayette), she caught fire, was filled with water by the New York Fire Department and capsized in the Hudson mud. Though she was eventually refloated, it was deemed too costly to convert her to a new use and the great liner was cut up in New Jersey shortly after the peace. Her luckier old rival, Queen Mary, sailed on for thirty years and is still afloat, if not at sea.

Ask an American or Englishman today what the word “Normandy” brings to mind and the answer likely will be a pretty place in France or D-Day and the gray beaches where the Allies first breached Hitler’s West Wall. Except for steamship connoisseurs, “Normandy” won’t mean Normandie. This is sad, not just because this particular ship was the most de luxe ever to set sail, a thing of beauty lost too soon and thus easy to grow nostalgic over. Rather it is because of her perfection of a narrower claim, to do with cooking and dining as an expression of nationality and culture. Aboard cruise ships nowadays (only one true ocean liner designed for the Atlantic crossing remains, Queen Mary 2), you will find a predictable array of “global” restaurants and “ethnic” offerings that manage to achieve, from one ship to another, the boring uniformity of diversity. More bracing, and refined, national tastes once ruled the waves in Normandie’s grande salle à manger, the biggest and proudest French restaurant of them all.

My Chicago family re-boarded Normandie for home on August 26, 1936 at Southampton, cases and trunks filled with photographs and memorabilia from the journey. Among the festive ribbons and party hats, they saved the menu from the final meal of the voyage: lunch, served just before docking at Pier 88 on August 31. It is a smaller card with abbreviated choices (though still, if you wished, seven courses), embossed with the blue, red and gold French Line crest. The family did not linger in New York, and the Broadway Limited had them home again next morning. Chicago was known as a meat-and-potatoes town never famous for la haute cuisine. But there were a few French bastions of the right sort, in those years — Café de Paris, Chez Paul, L’Aiglon — where one might resort from time to time for that special-occasion treat, perhaps re-living memories of Normandie crossings and the old Europe, before the lights went out.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply