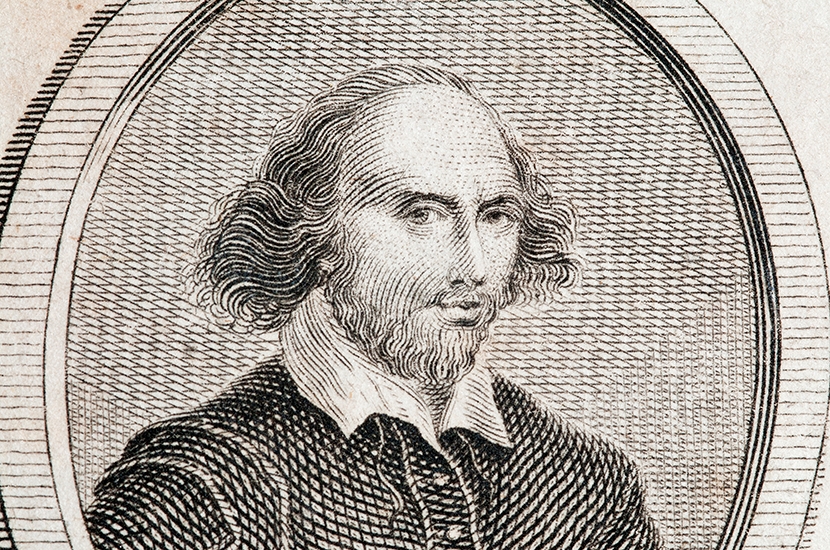

‘Now I am cabined, cribbed, confined, bound in To saucy doubts and fears.’

Shakespeare got there first, as ever, and he probably knew a thing or two about being in quarantine. The plague lurked darkly, and people were as aware of its dangers as we are of COVID-19. The theaters definitely closed, so it is likely that he wrote while self-isolating. Which is exactly what I am doing, with laptop on the kitchen sofa, tea at my elbow, spring sunshine pouring in. Four long-tailed tits, two robins and a bustle of hedge sparrows are busy shoving one another off the bird table outside. Our resident barn owl skimmed by earlier.

Lucky that can I walk in the garden and meadow, or down our quiet lane of an evening, but otherwise, we are strictly quarantined. I am well, but 78. My partner is having treatment for breast cancer, so is immunocompromised. Working from home is business as usual for a novelist and a screenwriter, but usually we get out, shop, have coffee, travel to London for meetings, see friends. Normal life. Not any more.

It was when I ran out of stuff to do, apart from work, that I realized things had changed. A self-isolating neighbor and I were walking our dogs down the lane at the recommended distance apart, and stopped to chat about what we were up to in between hand-washing.

She said she was turning out every drawer, cupboard, wardrobe and shelf, deep-cleaning them, sorting stuff into ‘keep’, ‘charity shop’ and ‘bin’, then she would be taking down all the curtains to wash and repair. I expected her to say next would come sides-to-middling the sheets. She is the kind of woman I am not.

Back indoors, I opened a few drawers and a wardrobe, shut them again quickly, and went up the attic stairs. My way was blocked by a silver-painted wicker reindeer, a washing basket full of baubles and the usual massed tangle of tree lights. It’s March and we haven’t even put Christmas away properly yet.

Now I have time on my hands, jobs must be done. I will make a list. Do you fully understand the power of lists? Once you have made them you know in your bones that, not only have you written down the jobs that need doing, but you have actually done them.

For the foreseeable, there are no cozy pub suppers, trips to town, theater, concert or cinema, and I am not a TV watcher. But I can’t just twiddle my thumbs, and I probably read too much as it is. I need a hobby. I have started making a list.

None of this is either fun nor funny, of course. I am trying to keep a lid on my anxiety but it flutters there below the surface. I haven’t felt so worried about a world situation since the Bay of Pigs crisis when I was a student in London and it brought back childhood memories, not so much of the war — I was only three when it ended — but of the atmosphere of war. Air pollution has decreased substantially and globally since the COVID-19 crisis began, but anxiety levels are at a wartime high.

The internet is a lifeline, though the news is more of a death one, and to preserve sanity I only check it once a day, and social media is a toxic zone. I gave up Twitter for Lent but I use Facebook to keep up with friends I rarely seem and there are also handy groups for local information, which are an eye-opener, I can tell you. How else would I learn about people knocking over old ladies in the rush to grab toilet rolls, queuing cheek-by-jowl for takeaways without thought of distancing, or indeed, about those posses offering to shop, collect meds, walk dogs and generally be good neighbors?

And then there are the bright ideas. ‘Let’s all put our Christmas lights back up.’ ‘Let’s post a picture of a rainbow in the window. We can make a rainbow trail.’ ‘Let’s all lean out of our windows at seven tonight and applaud the angels of our wonderful NHS.’ It restores my faith in human nature.

I read at least a book a day, swinging between heavy and light, classic and modern, fiction and non. This week I am back to Thomas Hardy, a longtime love I have neglected, so let me remind you of his masterpiece, The Mayor of Casterbridge. Tess of the d’Urbervilles is too distressing for these times. A friend has been reading Shakespeare and says the same of King Lear: ‘I just can’t go through all that again right now.’ My standby comfort and cheer book has long been Nancy Mitford’s The Pursuit of Love, a friend which has seen me through some very dark days. There are limits to froth, though — notably any book, and there has been a proliferation of them this year, with the words ‘little café’ in the title. The only book I know of any worth that includes the word ‘café’ at all is Carson McCullers’s strange, spiky, gothic novella The Ballad of the Sad Café. But these new, candyfloss ones are a self-spawning genre of their own and the jackets are all of a kind, too, with pastel drawings of, well, little cafés, and titles in swirly writing so you can recognize one even if you can’t read.

Where did they come from? Of course they are perfectly harmless and I am being snobby. In fact I plan to write one myself if I am locked up for longer than the time it takes me to finish my new crime novel, a book of essays, and a memoir. I am calling it Lockdown in the Little Coronavirus Café.

One thing you can safely let into your home are deliveries, so books can still pour in. You stay quite safe by not signing for them on the courier’s germy electronic pad and leaving the box untouched for 24 hours. You then open it, wash your hands (again) and pull out those luscious literary plums. I have been told that the virus doesn’t survive longer than that on paper, but don’t quote me, it’s probably fake news.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.