Goose-pulling is dead and gone, and lawn darts are on life support, but roque is alive and well and avoiding the roster of extinct sports thanks to the good folks of Angelica, an attractive village of fewer than 1,000 souls in the southwestern corner of New York State.

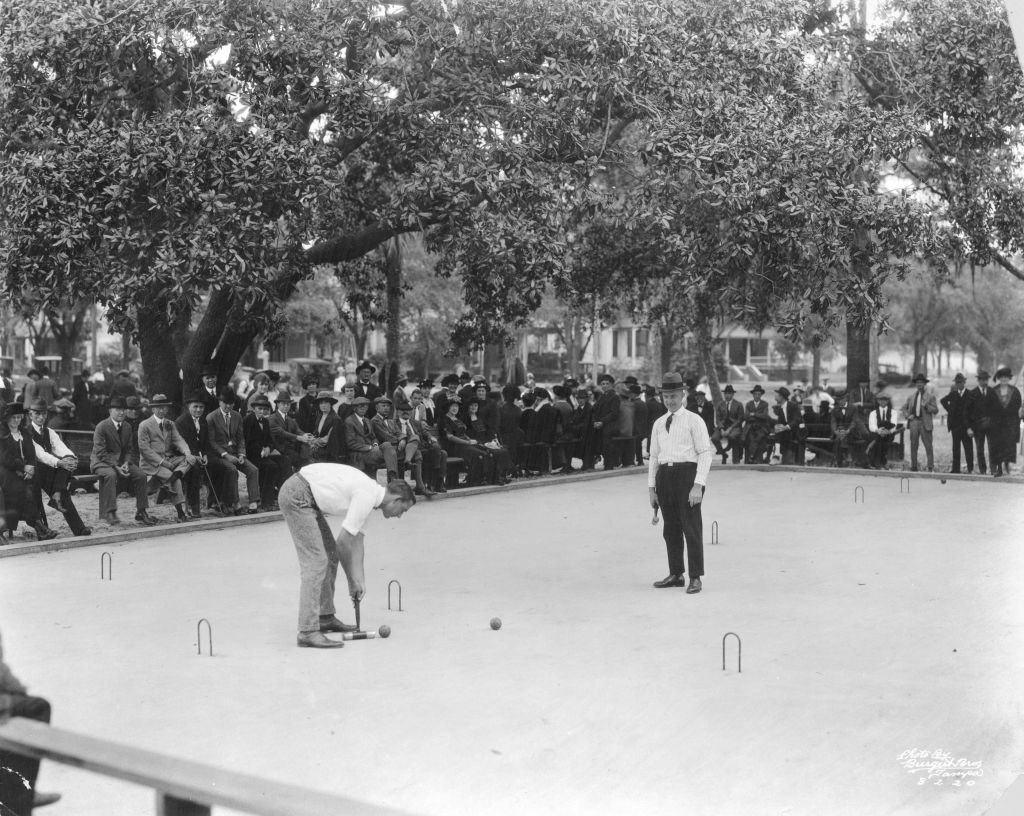

What’s that: you’ve never heard of roque? Affix a “c” to its left and a “t” to its right and you have its sporting parent. Roque is a nineteenth-century American variation on the erstwhile European pastime of the leisure class. A hybrid of croquet and billiards, it is played on an oval-octagonal court of sand and clay with fixed wickets and hardwood boundaries off which a player can ricochet shots. Its mallets, shorter than those used in croquet, are now either homemade or handed down from roquers past.

Roque enjoyed a brief vogue. It was a medal sport at the 1904 Olympics in St. Louis, where Americans swept the gold, silver and bronze. (The only non-medalist was also American.) Public courts appeared here and there in the 1930s, courtesy of the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration, but it just never caught on — except in Angelica, where Angelican exceptionalism has preserved an old court and transmitted a love, or at least liking, of the game to generations.

So on the first weekend of every August, Angelica, which was named for Alexander Hamilton’s sister-in-law, Angelica Schuyler Church, hosts a roque tournament in its village park during “Heritage Days.” Amid craft vendors and Amish bakers and singers belting out classic country tunes, the only roque tournament in the world proceeds at an unhurried pace.

Jim Gallman, seventy-eight, is Angelica’s tender of the roque flame. You can catch him every Tuesday morning at 9 a.m. as he booms “Good morning, Angelica!” over community radio station WRAQ 92.7-FM. How long has Jim been playing roque? “Since after the Civil War.” He waits a beat. “Of course today is after the Civil War, too.”

Jim took up the mallet in the 1950s, and while “the tremors” have sidelined him, he keeps close watch on the action from his courtside chair. Jim tried to explain the game’s byzantine rules to me, but that effort was as hopeless as elucidating particle physics to a TikTok teenager. Basically, you thwack the ball through a series of iron arches, using the walls if necessary, and eventually you hit the home peg. A best-of-three match between two-person teams might take ninety minutes.

A healthy percentage of the thirty or so area roquers are Jim Gallman-adjacent. “There’s my brother,” he says, pointing to one player. “This is my son-in-law. That’s my cousin’s son.” And so on.

The last rulebook was published by the long-defunct American Roque League circa 1960. (It wistfully — or delusionally — called roque “the game of the century.”) Jim tells me that someone once showed him a copy, but the rules didn’t correspond with those handed down by tradition in Angelica, so the locals ignored it. “We’re interested in how we play, not how they played,” he states with admirable firmness.

That’s the spirit. Angelica Rules!

Jim Gallman has never seen another roque court, though press reports indicate that there may be private courts in Stuart, Florida and on Cape Cod. I hope they play by similarly localized rules.

The players are competitive but peaceable. I saw no fights. Yet the two most prominent mentions of roque in popular culture are bloodstained. In John Steinbeck’s unheralded novel Sweet Thursday (1954), the neighboring communities of Monterey and Pacific Grove, California, come to blows over a tournament, leading to the discovery of one unfortunate who is “found clubbed to death with a roque mallet in the woods.”

Stephen King, in The Shining (1977), has Jack Torrance explain the game to his wife and son, the Red Rum tyke. (“It’s a little bit like croquet, only you play it on a gravel court that has sides like a big billiard table instead of grass.”) Jack praises the hardness of the mallet with which he later tries to beat his wife to a pulp. Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 film adaptation discarded the roque mallet, substituting a ho-hum ax. Every detail of Kubrick’s horror masterpiece has been parsed by obsessives, so I ask the Room 237 crowd: what did the old boy have against roque? Did operatives of the American Roque League get to him? Or was he respecting Angelica’s uniqueness, keeping its secret safe from the world?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2023 World edition.