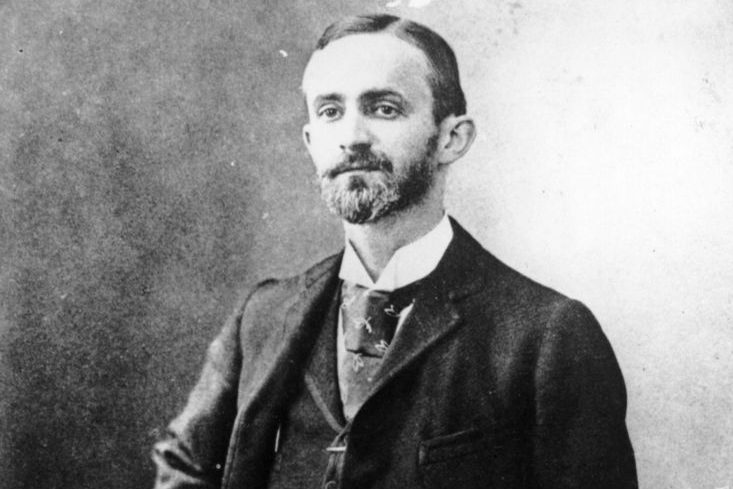

George Eastman, founder of Eastman Kodak and benefactor of Rochester, New York, told my late friend Henry Clune (1890-1995 — and no, that’s not a typo) that he had never laughed until he was forty — and the camera tycoon wasn’t exactly a chuckle-factory in his old age, either. Eastman put an end to the grimness with a bullet to his head in 1932. He left a suicide note that read, “My work is done — Why wait?”

Clune, star reporter of the Gannett newspapers, habitué of poolhalls and burlesque palaces and country clubs, a man who read Macaulay for enjoyment and composed panegyrics to strippers and barkeeps, occasionally visited the “lonesome little old man” in his home or office. (Henry’s mother had coated photographic plates for Eastman’s fledgling company in 1881.) “He was courteous enough,” recalled Henry, “and he may have smiled. I do not remember. But there was no fun in him, and a belly laugh would have been beyond his capacity.”

Two decades after Eastman entered the last darkroom, Henry Clune published a thinly veiled roman-à-clef about the morose magnate. He wanted to call the novel The Stars Have Monstrous Eyes, but editor Cecil Scott of Macmillan, oblivious of the imaginative range of juvenile humor, retitled it By His Own Hand. Now, Eastman had been a seemingly asexual bachelor, but come on, let’s not rub it in. Henry acceded to the change, not least because Macmillan president George Brett (not the Kansas City Royals Hall of Fame third baseman) told him that in his “considered judgment,” By His Own Hand would be “the greatest popular success we have had since Gone with the Wind.”

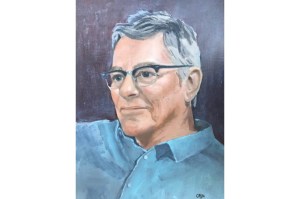

It wasn’t, though By His Own Hand is a finely observed story of business and the upper-middle class of a midsized city. Acknowledging that friendship may color my opinion, I’d put the book on a shelf with works by Booth Tarkington and John O’Hara. I recently revisited Henry’s novel, prompted by a fond remembrance of Martin Morse Wooster, one of the outstanding characters of this era’s Washington journalism.

Martin was, well, how to put this? He was hulking, he was the messiest eater I have ever known, he was not always attentive to the proper arrangement of his clothes — and he was a man of sweet disposition, insatiable curiosity, a marvelous catholicity of interests and a talent for friendship as massive as he.

Martin was killed by a hit-and-run driver in November 2022 while walking back to his hotel from a conference on “Ale Through the Ages” in Williamsburg, Virginia. The outpouring of affectionate eulogies could have flooded the Potomac.

I last saw Martin weeks before his death. I was speaking in DC on a panel dedicated to another friend, the late Representative Barber Conable, a sterling congressman of rare rectitude, intelligence and rootedness. Martin sat in the front row. He came up to me afterward and in the midst of this moderate Republican-flavored gathering burst into a robustly off-key rendition of a Barry Goldwater campaign song.

Oh, Martin, I wish I could hear you sing again.

Martin’s pet subjects included the lives of great philanthropists. I don’t believe he ever visited Rochester, but he wrote admiringly of George Eastman’s spend-it-while-you’re-alive philosophy.

The never-married Eastman, who died without issue, said, “It’s more fun to give away money than to will it.” So he gave away $125 million, with nary a foundation staffer or GiveWell human algorithm in sight. Aside from his gifts to MIT, the Tuskegee Institute and the Hampton Institute, Eastman’s philanthropy was almost entirely local, which is why Rochester is graced with an Eastman School of Music, an Eastman Theater, and a first-rate medical school. His favorite charity was the University of Rochester, my alma mater, but he cannot be blamed for that.

His patronage of the musical arts stirred something in the aging Maecenas and even produced one of the exceedingly few amusing Eastman anecdotes.

It seems that George Eastman was bewitched by the beautiful operatic soprano Mary Garden, for whom he hosted a lavish dinner party in Rochester. Miss Garden was wearing, in Henry Clune’s description, “an evening gown that left her magnificent shoulders free even of supporting straps.”

Sneaking peeks, Eastman ventured upon flirtatiousness.

“I can’t understand, Miss Garden, what it is that holds up that dress.”

“Only your age, Mr. Eastman,” she replied with a mischievous sparkle, “only your age.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply