A match-fixing scandal centered on FC Barcelona has spilled over into politics, showing that decades-old divisions die hard in Spain. Triggered by the so-called “Negreira Case,” which concerns payments of €6.7 million (about $7.4 million) allegedly made by Barca to a company linked to a Spanish refereeing official between 2001-18, Real Madrid and their greatest rival are accusing each other of links to Francisco Franco, the fascist dictator who ruled the country from 1936 to his death in 1975.

The row started last week, when Barca’s president Joan Laporta claimed that if any Spanish club should be subject to suspicions of referee favoritism, it’s Los Blancos, which he provocatively described as the “team of the regime.” Real Madrid immediately returned the accusations of cozying up to Franco. In a brief video posted on YouTube called “Who Was The Team of Regime?”, it pointed out a few carefully-selected facts: that FC Barcelona gave the dictator two medals in the 1970s (both of which were revoked by the club in 2019), made him an honorary member in 1965, received financial assistance from his regime and that the team’s stadium, Camp Nou, was inaugurated by Francoist minister Jose Solis Ruizin in 1957.

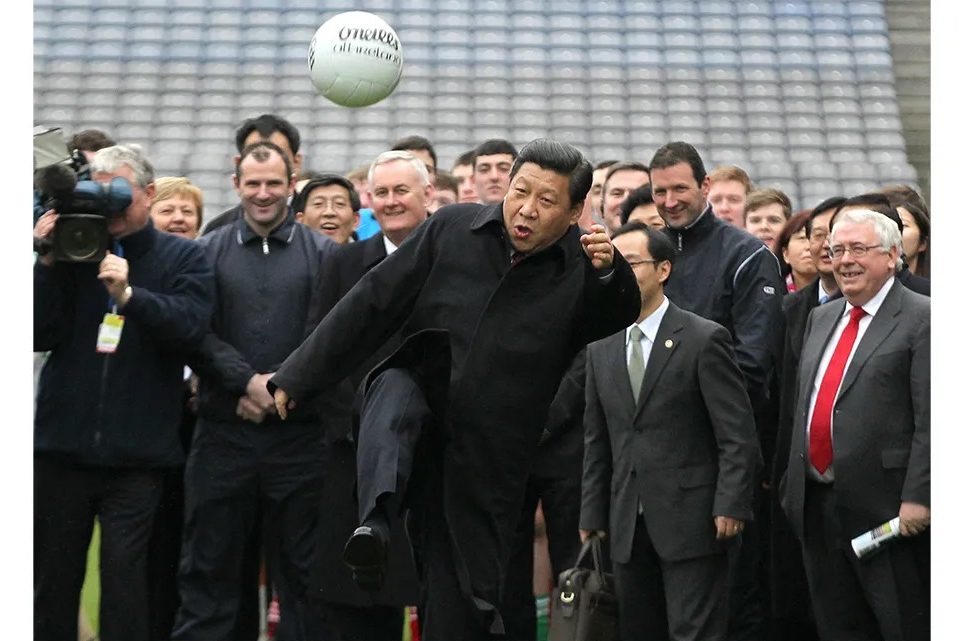

FC Barcelona gave the dictator two medals in the 1970s

Isabel Díaz Ayuso, the Conservative president of Madrid, described the video as “magnificent.” It was a timely corrective, she said, to what the Spanish right sees as a biased “historical memory” movement.

Patrícia Plaja Pérez, spokeswoman for the Catalan government, took a rather different line, branding it “indecent fake news” and “an offense to people who suffered under the regime.” Plaja claimed that Madrid seemed to have forgotten about Josep Sunyol, a prominent Catalan separatist and Barca president at the time of his death in August 1936, at the hands of Francoist troops. Franco imposed a zero-tolerance policy on Catalan culture: speaking Catalan in public and teaching it in schools was banned, as were pro-independence symbols from Barca’s crest.

Raking over such an acrimonious period of Spain’s past won’t do either team any good. Though Laporta’s accusation is not without historical basis, there is evidence of collusion or at least sporadic contact with the dictatorship on both sides. This shouldn’t be surprising: Franco presided over a repressive totalitarian regime for almost four decades. Spanish writer Javier Cercas has argued (most notably in his 2014 non-fiction work The Impostor) that many individuals — like the subject of that book, a virtuoso fraudster named Enric Marco — who claim to have been anti-Francoists during the dictatorship were, if not actively complicit with the regime, at least not openly defiant of it. Survival necessitated compliance. This applies to soccer clubs as much as it does to individuals — which is not to say that Barca, and Catalonia as a whole, didn’t suffer under Franco.

There has always been a political dimension to the rivalry between Barca and Real Madrid, whose matches are referred to as El Clasico. Ever since the latter was branded “real” (royal) by King Alfonso XIII in 1920, it has been regarded as the pampered team of the establishment, supported by unionist Conservatives, the Catholic church, the monarchy and, during the dictatorship, Franco himself. The autocracy made no secret of this, pumping money into the club and using it as a symbol of a unified Spain. Fernando Mariá Castiella, the regime’s foreign minister from 1957-69, called Real Madrid the “best embassy we have ever had.” It’s even been rumored that Franco himself visited Barca’s dressing rooms before an infamous 1943 match with Real Madrid, although it was most probably the head of his terrifying “security” forces. Whoever it was, their pre-game talk had the desired effect: despite having beaten Real Madrid 3-0 in their previous encounter, Barca lost 1-11. It remains the biggest defeat in the history of El Clasico.

Barca, by contrast, is the team of the progressive left and Catalan separatists. Sunyol, the Barca president shot by Francoists in 1936, embodied the political ideology with which the club is still associated. A member of the leftist ERC (the pro-independence party to which the current Catalan president, Pere Aragonès, also belongs), he founded an anti-establishment newspaper called La Rambla in 1930. Today, meetings between the two teams are often used as de facto demonstrations for Catalan independence by Barcelona supporters. During a Clasico in December 2019, Barca fans in Camp Nou waved banners urging the Spanish government to “sit and talk” with separatists; meanwhile, outside the stadium, pro-independence protesters clashed with police.

The symbolism of the Barca-Real Madrid rivalry is as potent today as ever: a win by Los Blancos is a victory for los pijos (the posh) and the establishment, while a Barca triumph is cause for celebration by radicals, rebels and separatists. Laporta no doubt knew that all he had to do to divert attention away from the match-fixing allegations against Barca was to reignite decades-old animosities: if dragging Franco into the dispute was a deflection strategy, it worked brilliantly.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.