Towards the end of April, my mother sent me a letter. She doesn’t write as a rule — we speak on the phone — but this time she sent something. It’s hard to explain the effect her handwriting had on me after so many months of being apart. It was as if she was there, in envelope form, on the doormat.

And because her handwriting’s been so familiar for so long, it wasn’t simply my mum as she is now, but Mum through three decades. I stood there in the gloom of the hall, vertiginous with memory, and I realized how unlikely it is that any future generation will have this same experience.

I’m Generation X, the last of the analogue gang, brought up on handwriting. Our things weren’t encoded, they were imprinted: records and tapes. We had calligraphy sets, and as teens hand-wrote self-conscious love letters. Our crime dramas, back in the 1990s, inevitably involved a graphologist who could spot a psycho by the deviant slant of his writing. Psychos always wrote notes in those days. I have a feeling that the FBI and our Special Branch actually did employ graphologists back then, though I hope I’m wrong. We were the last generation to be snotty about fountain pens: ‘No, sorry, you can’t borrow it. You’ll ruin the nib.’ And we’ll be the last to understand what it is to recognize someone so completely in the slants and loops of their handwriting.

Handwriting is fading, that’s a fact. Though British schools still teach joined-up cursive script, in America it’s optional, up to each individual state, and many of them don’t see the point. If handwriting’s taught at all it’s printed writing — each letter separate and isolated, and most children type their notes. Typing is less discriminatory, they say, and what’s the point of anything else? The future is via keyboard. Schoolchildren don’t practice their signatures anymore; in fact banks complain that the kids don’t even have signatures these day. And even if they do handwrite their essays, all kids communicate via text.

The 21st century is the age of the smartphone and its camera. Teens take selfies. Parents take photos of children, obsessively, grimly, though no one can now remember why. There are 9,000 photos on my phone, as I swipe back — not one of them as evocative as a single handwritten line.

A photo contains a moment, often a fraudulent one. ‘Smile darling, come on, just do it.’ Handwriting, even just the sight of it, summons a person, and sometimes, because handwriting is heritable, it summons their ancestors too. In my family, handwriting is matrilineal. My mum’s handwriting contains within it the echo of her sister’s; they both write like their mother, and her mother too. As I stood there in the hall, having my Proustian moment, Mum’s dashing capitals brought back my grandmother’s postcards, her handwritten recipes, the biro’d labels stuck to frozen joints of meat. As I wrote this, by hand, I could see my words pulled into familiar matriarchal shapes.

No one quite knows why handwriting runs in families. There’s some speculation that it’s to do with bones and muscles — the way your inherited hand holds a pen. Others think it’s unconscious copying. I don’t expect it’ll be worth anyone’s while to find out now.

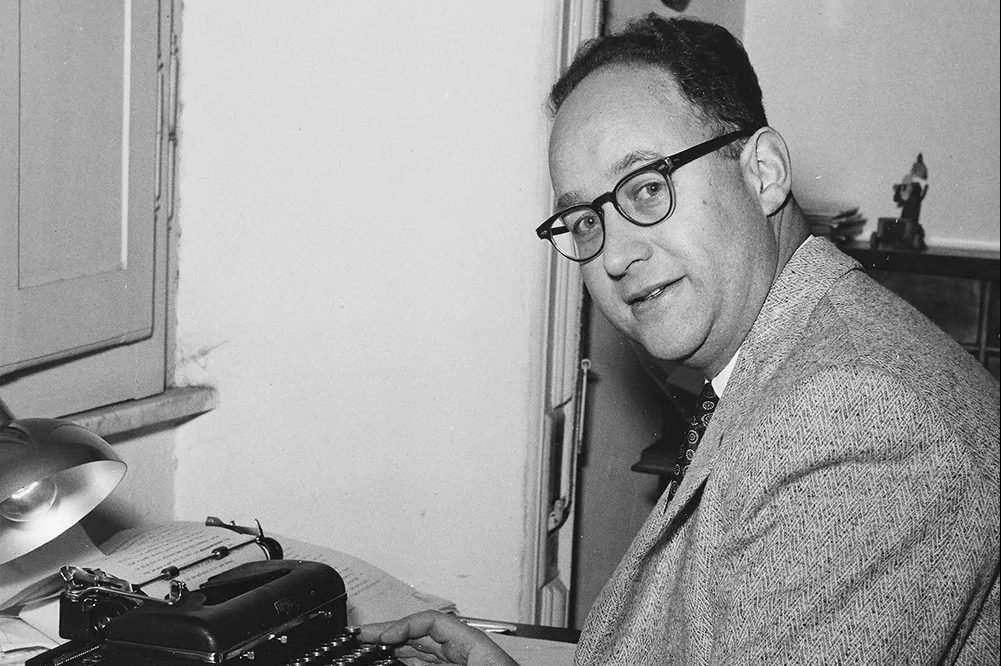

The best book on handwriting that I can find oddly doubles as a rousing cheer for its demise — perhaps because the author’s son (she admits) found handwriting hard. We’re living through a transitional moment, says Anne Trubek, in The History and Uncertain Future of Handwriting. Yes, handwriting is on its way out, but we’re living through a golden age of writing too, almost as a direct result. ‘Although we may disagree on the merits and de-merits of cursive instruction…most Americans write hundreds if not thousands more words a day than they did 10 or 20 years ago. We have supplanted much talking and phone calling with texting, emailing and social media. One of the most surprising aspects of the digital revolution, in fact, is how very text-based it has been.’

I like Anne’s optimism, but there’s writing and writing. I read, in another academic paean to text messaging, that emojis have added back into texted life a sense of the fun and individual character that handwriting once allowed. This is clearly cobblers. Emojis make any messages not more different but more horribly uniform. Those nasty little faces impose their own distinctive character on a text, obscuring the sender, and in my book they’re borderline demonic. That one with the sinister blind heart eyes; that sly face blowing sideways kisses. Is it even possible to blow a kiss and wink simultaneously?

‘Perhaps, in the future we’ll teach handwriting in art class, and encourage calligraphers as we do letter-press printers and stained-glass-window makers. These arts have a life beyond nostalgia,’ suggests Trubek, in the manner of someone who, having safely buried a body, places a flower on the grave. But I don’t want uniform handwriting or calligraphy. I want the look of each person’s individual hand. I want that weird feeling that they’re present in each stroke.

Handwriting won’t vanish straight away, that’s for sure. There won’t be a poignant interview with the England’s last hand-writer come 2050, because, as Trubek says, different forms of communication can co-exist and overlap. They always have. The printing press didn’t kill handwriting, it pretty much invented it. The professional scribes who once copied out books were stuck for work when the presses started up, so they taught handwriting to the masses.

On Monday, when cafés open up in the UK again, there will be people swiping and tapping; people muttering through their masks at Siri, ladies with biros doing Sudoku, students underlining texts. ‘The shift away from handwriting will bring about losses. But those losses will also give rise to changes — in accessibility, in democratization, in advantages unimaginable to us now — that should be celebrated,’ says Trubek. I can’t celebrate it. I can perhaps accept it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.