Greece

While green Rhodes and greener Corfu burn away, arid Patmos remains fireproof because rock and soil do not a bonfire make. The Almighty granted some islands plenty of water, and other ones no H2O whatsoever. Most of the Cycladic isles lug in drinking water from the mainland, and make do with treated unsalted seawater for planting. The Ionian isles have springs and rivers and also fires, some of them started by firebugs who hope to gain — I have never figured this one out — from the blaze. It’s all very confusing, especially as the temperatures are rising and the energy to party diminishes by the hour.

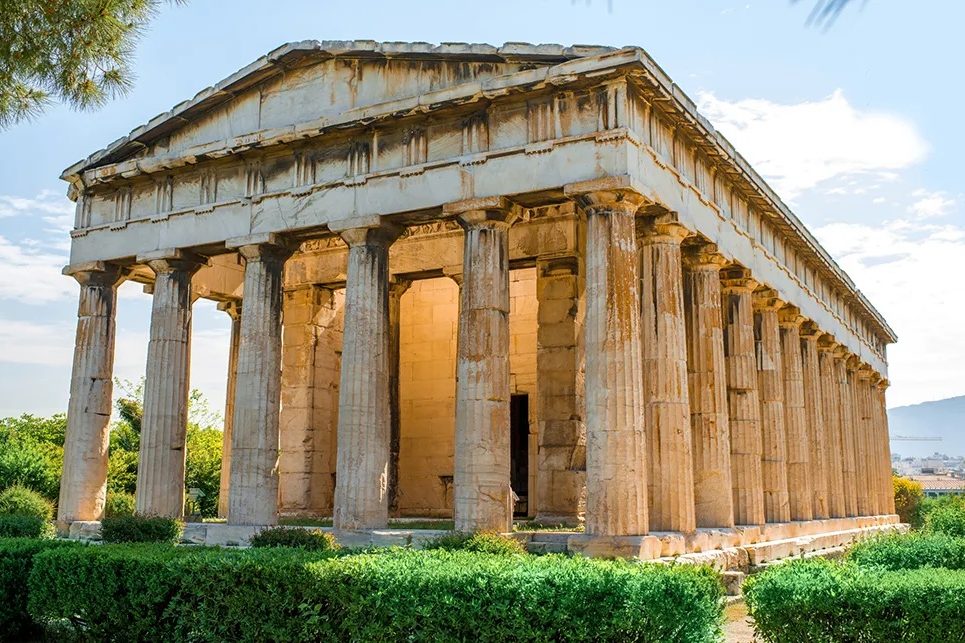

The Greeks have always been obsessed with fire. We worshipped Hephaistos, god of fire, and his temple northwest of the Acropolis was the scene of ferocious fighting between nationalists and commies back in 1944. I was eight years old at the time, but members of my family, including old Dad, made up for it. If anyone is interested, the good guys won with help from the Brits, and the bad ones retired to the mountains up north and eventually went over to the Soviet Union where they learned to speak Russian fluently. The winners chose capitalism and you can guess the rest. As a famous wit once remarked, had the commies won, he didn’t think Aristotle Socrates Onassis would have chosen the widow Khrushchev for a bride.

Never mind the witticisms, Patmos is as hot as it gets without the Hephaistian orgies that took place on Rhodes. However scary a fire can be, it is somehow less frightening when on an island: one can always plunge into the blue Mediterranean and give the god of fire an old-fashioned middle-finger salute.

I first came to Patmos when visitors — all on their boats, naturally — had names like Guinness, Guest and Goulandris. The town was made up of whitewashed stone houses clustered underneath the great St. John monastery way up high, where the baddies could not reach. This was and still is called Hora, while the port below goes by the name of Skala. Hora and Skala were small in those days, with a few tavernas and people who all knew each other. Fifty-odd years later, as with middle-age spread, both H. and S. have grown exponentially, but the locals have somehow managed not to go Mykonian and greedy.

Patmos used to be visited by a lucky few because it’s much closer to Turkey than to the Greek mainland. That was then, however, and now daily overnight ferry services from Athens disgorge their cargoes and you can guess the rest. Still, Plateia is the main square and meeting place up in Hora, where the elite meet to eat and exchange gossip. Plateia is round, with a great outdoor bar on the higher end run by George and Maria, the two nicest people on the island, who are helped by Michael, equally gentle. That is where the tongue-tied so-called golden youths hang out, while the rest of the place has Mister Manolis as King, dispensing dinner tables like a benevolent pharaoh. Needless to say, George, Maria, Michael and Manolis are good friends and take great care of the poor little Greek boy when he’s under the influence.

And speaking of influence, Christos Zampounis, my Greek editor, has been given the credit, by those in the know, for a pro-royal swing of at least 10 percent of the population after his pro-royal coverage on TV debates following the death of King Constantine earlier this year. As laconic as a Spartan, Zampounis asked the anti-royalists only one question: “Was he or was he not head of state?” “Yes, but…” were the answers. In spite of this, the king was refused a state funeral. I told my friend and editor something he knows quite well: we Greeks can be the tops at times, but also among the pettiest.

Otherwise everything was hunky-dory until my daughter decided to give a party in my house, rather than hers, for about twenty of her friends. Word got out and my fifteen-year-old granddaughter Maria asked me whether she could have a few youngsters drop by after dinner. While we oldies were dining in the garden, the youngsters came in and kept coming in and then they all disappeared. When the wife was going up to bed around 2 a.m. she noticed a long line of very young people coming through an opening and very politely saying thank you and goodbye. She counted around fifty of them. The young had all gone up to the terrace, taken bottles of vodka lined up for senior consumption, and whatever other liquor they could find, downed it, and then politely left thanking the wife. I never saw them as I was under the weather in the garden, but everyone got home safe, according to my granddaughter who has a telephone implanted in her ear. The only two to miss the festivities were Antonius and Theodora, aged four and two, my other two grandchildren who were sleeping at their mother’s.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.