When rulers are thrown out of their countries, they cannot expect all that much. Think of Napoleon, first cooling his heels in Elba, then ending his days in the damp-infested confines of Saint Helena. Which is why the former Edward VIII, later the Duke of Windsor, was comparatively fortunate that the Parisian spot in which he found himself living after his abdication in December 1936 was Le Meurice in Paris: then, as now, a hotel that offers not only glitteringly luxurious accommodation to its well-heeled denizens, but a tangible sense of history — its lavishly appointed suites and restaurants exude an atmosphere that’s simultaneously relaxing and conspiratorial. Turn an unexpected corner, and you half-expect to see the ghost of Wallis Simpson, barking orders at some hapless minion. Which is, very much, as it was.

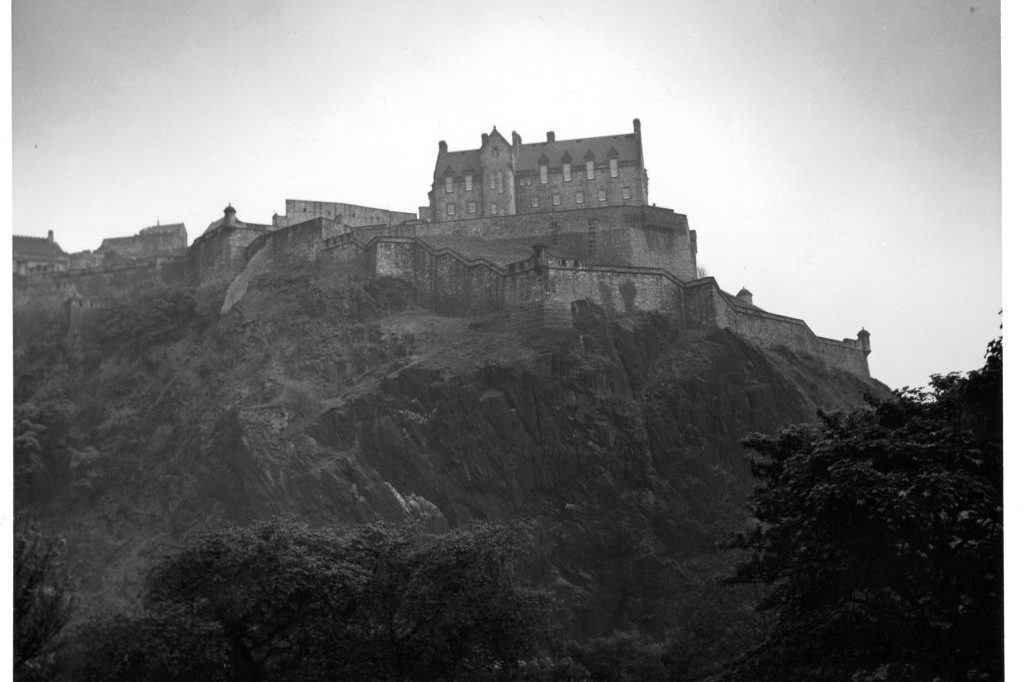

The Windsors’ choice of Le Meurice as their Parisian home-from-home between their wedding in June 1937 and the invasion of France three years later was no coincidence. When it opened in 1835, a stone’s throw from the Louvre, its founder Charles-Augustin Meurice had an especially lucrative plan. His aim was to construct a hotel that would be particularly appealing to English visitors to Paris, combining the seigneurial atmosphere of a grand palace with the creature comforts homesick travelers might expect. It soon became a particular favorite with the great and the good; it was known (with a touch of irony from a country that only finally banished its monarchy in 1848) as the “Hôtel des Rois.” It received the royal imprimatur when Queen Victoria commandeered the entire first floor in 1855 for her state visit to France: it is impossible to imagine that she was unamused by the lavish fawning she no doubt received.

The Duke and Duchess of Windsor, however, were a rather different breed of royalty. After the abdication crisis, the duke was not allowed back to Britain until the outbreak of World War Two, and so they lingered in their suites at Le Meurice, less as honored guests and more as increasingly irritable lounge lizards. They were visited at the hotel by everyone from Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain to the duke’s brother the Duke of Gloucester, all of whom took a certain rapturous delight in noticing how much higher the standards of food, service and, naturellement, wine were in Paris than in tiresome old London, where members’-club carbohydrate-and-claret remained the order of the day in even the grandest establishments. Charles-Augustin’s influence was alive and well, over a century after his hotel opened.

When I stroll into the ornate entrance hall at Le Meurice, it isn’t hard to see what so enraptured Edward, Wallis and their high-profile guests. Today, the hotel is owned by the reliably excellent Dorchester Collection, and one walks off the Rue de Rivoli and through the revolving doors with a happy sense of knowing, as Holly Golightly says of Tiffany’s, that nothing bad could possibly happen to you inside its walls. If you’re lucky enough to be checked into one of the impossibly comfortable suites overlooking the Tuileries, sipping a glass of Champagne and generally taking stock of your standing in the world, then it’s easy to feel that the Duke and Duchess weren’t that hard done-by. Although the twenty-first-century mod cons of enormous marble bathrooms and absurdly deep and comfortable beds — now de rigueur for a hotel of this expense — were, presumably, not standard back in 1939.

It is also tempting to wonder what on earth Edward and Wallis would have made of the Philippe Starck-designed Restaurant Le Dalí on the ground floor. Named after another famous resident of the hotel, who lived in Paris at the same time the duke and duchess were hanging around — oh to have been a fly on the wall for that conversation! — it’s a riot of color and imagination, decorated with aplomb and bracingly bizarre in its juxtaposition of the old and the forward-looking. If the menu isn’t anything like as imaginative as the setting, it’s still a hugely entertaining selection of bistro favorites, of which squash-flower tempura and a suitably regal filet steak are the best. And, naturally, the top-notch wine selection remains one of the most entertainingly comprehensive in the capital.

After a suitably Wallis-esque room-service breakfast (oh, the pain au chocolat haunts my dreams still), it was time to see how the other half lives, and so I traveled the mile or so to Le Meurice’s sister hotel, the Plaza Athénée. If Le Meurice was where Edward and Wallis received their high-profile guests in somber and statesmanlike fashion, the Plaza Athénée was where they went to have fun. Its setting, amid the oh-so-cher boutiques of avenue Montaigne, benevolently overseen by the Eiffel Tower, screams plutocracy, and the hotel itself has always attracted a more raffish, bohemian set than the other grand Parisian palaces; there’s a famous picture of Harrison Ford leaving there in 1980, looking every inch the debonair man-about-town rather than a space pirate or Thirties archaeologist. And it’s little surprise that the duke and duchess let their hair down here, especially in the hotel’s famous Le Relais Plaza Bistro: it opened shortly after he abdicated, on December 30, 1936.

Arguably, there’s no place in Paris so synonymous with a certain kind of celebrity: discretion-seeking, moneyed and in search of the finest things euros can buy. A vast photograph of Wallis can be seen as you enter the restaurant, as if glaring down on those who have followed in her footsteps, but you’re more likely to see the likes of Leonardo DiCaprio and Jay-Z here these days. Still, as you peruse chef Jean Imbert’s menu — heavy on elaborate takes on such brasserie staples as escargots, beef filet in brioche with foie gras and rum baba — it’s hard not to feel a sense of amused nostalgia, given that both Edward and Wallis were notoriously diet-conscious (he would frequently stop eating altogether at moments of stress, and she is said to have held that “you can never be too rich or too thin”) and would almost certainly have caviled at anything more substantial than the lamb’s lettuce salad and black truffle on the menu. And, on the occasions that they would have hosted a table at the Relais Plaza, it is tempting to imagine Wallis taking careful notes of the evening’s strengths and weaknesses, to be much discussed with her husband later: her servants referred to it, sardonically, as her “grumble book.”

No grumble book would be needed for a stay at the Plaza Athénée, which offers the highest standards of luxury imaginable, although I have to confess to the most first-world of problems: I stayed in a suite so large that it was actually a rather overwhelming experience, and I found myself waking anxiously in the night, half-fearing that I would be visited by the Duke of Windsor’s shade. If I had been given a talking-to by a former king about whom I’ve now written no fewer than three books (obsessed? moi?), I wonder what he might have said about the hotel he once patronized.

Given his notoriously demanding standards and unwillingness to compromise on the luxuries due to a former king, he would undoubtedly have made the staff’s life a misery. Yet I can also imagine that, if he’d knocked back in the hotel’s signature bar (called, wittily enough, Le Bar) with a glass or two of the Dom Pérignon Champagne they specialize in, he might have unbent, and even suggested that exile wasn’t too shabby, after all. The British ambassador to France, Sir Eric Phipps, wrote in May 1937, when the duke arrived there, that “it looks as though we must be prepared for a fairly prolonged stay in the country which may, I fear, raise a certain number of problems.” Had Edward known of his compatriot’s concerns, he might have asked him to buy him a glass of something strong at Le Meurice or the Plaza Athénée, sat him down, fixed him with the look of cold command he had perfected while king, and said, “You know that I only deserve the best things in life, don’t you?”

Judged by these two regal establishments — the “Hôtels des Rois” in excelsis — it’s likely that he would have had his wish, after all.

Alexander Larman’s new book, The Windsors at War: The King, His Brother & a Family Divided, is published by St. Martin’s Press. He was a guest of Le Meurice and the Plaza Athénée, Paris. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2023 World edition.