Traveling to Normandy fourteen years ago, we encountered a rare guide. He was a middle-aged Frenchman native to the neighborhood. I do not recall how long he had been at it, but he had learned something important about the guide business that was evident the day he shepherded us, and another American woman and her teenaged daughter, about the places made famous before any of us were born. He knew when to show, when to tell and when to relate something from his own experience that would enlighten ours.

He took things in a certain order, which was not the order I would have guessed. First we stopped at the German cemetery at La Cambe, where 21,200 of the some-80,000 German soldiers who died in Normandy are interred. I remember few other visitors. It is a somber place to this day, its stubby crosses and grave markers of black stone, not white like ours. Even its elevated central monument of a cross flanked by two dark figures in greatcoats seems to hug the ground. The Germans were well dug-in to that Normandy ground in June 1944 and did not spend their lives cheaply. Though almost a year would pass from D-Day to the final German surrender, for the Wehrmacht it was already late in the game. Manpower was running out. Our guide urged us to take time and read some of the markers. They told of officers in their early twenties and grunts no older than the sixteen-year-old girl in our party.

Everyone knows, and millions have visited, the great Normandy American Cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer, on its bluff overlooking Omaha Beach. It is the most visited of all American military cemeteries. All the sadness of lost youth hovers here too, but this is winners’ ground. Its serried rows of white crosses and Stars of David draw the eye upward and outward, across the English Channel. Nine thousand, three hundred and eighty-eight Americans rest here under markers etched with the soldier’s name, date of death and the unit he served in. The markers for 307 unknowns remain blank. The great bronze statue near the chapel, of a young man reaching upward out of the sea, symbolizes the youth of the great citizen army and its fallen. Like their adversaries, the Americans fell young here too: average age, twenty-four.

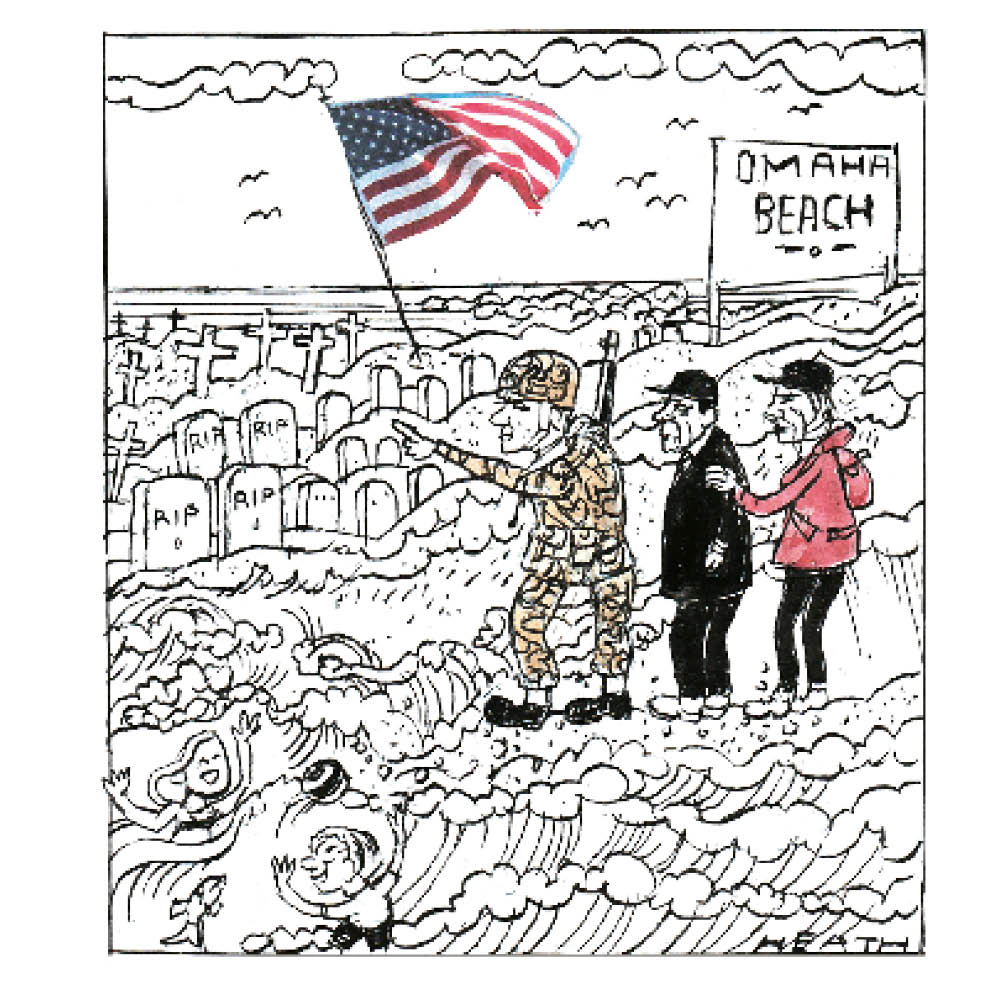

The visual experience is standard fare but no less stunning for that, and if you haven’t yet been to Colleville-sur-Mer (and, yes, La Cambe) do not fail to make the pilgrimage. It was something not seen, however, but heard — an anecdote told by our guide later in the day as we stood atop the remains of a concrete fortification down on Omaha Beach — that most sticks in this pilgrim’s mind. It is a remarkably unremarkable coastline, of gray sand and scrub vegetation rising inland, today built, if far from built-up, with some houses and commercial beach establishments of the sort that would be familiar to beachgoers anywhere. As we gazed over the scene, not knowing quite what to say, our guide, sensing our awkwardness, told us of another group of visiting Americans from a few years before when aging veterans of Operation Overlord still returned to pay their respects. He recalled how one visitor, probably in his fifties and too young to have served then but evidently wanting to sound patriotic (perhaps he was), expressed disgust at the signs of commercial activity along the beach:

“Just look at that; it’s awful, disrespectful, a disgrace. American boys died here. This place should be preserved just like it was back then, for them.”

The group grew quiet until a companion traveler, twenty or thirty years older, clearly of a less-polished background but who in fact had been there on D-Day, corrected his younger countryman:

“Hey Mac, shut it! Y’dunno what you’re talkin’ about. Families on the beach and kids playin’ in the sand: that’s what we did it for.”

Merci, monsieur le guide. I wish I could remember your name.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply