As I write this, London is so cold that I’m wearing a large, heavy, World War Two Russian army jacket, a wool hat, two pairs of thermal socks, long johns, a scarf and fingerless gloves that allow me to type — the kind Fagin wore in the film Oliver! — and I’m still freezing. But I won’t turn on the central heating because it costs too much.

But then, everything these days costs too much, so I’m making radical cuts in my expenditure. How radical? I now make one cup of tea, instead of a pot of tea with three bags. I’ve had to cut back on expensive organic foods — but I’ve kept the expensive organic sex lubricants. I think they call this genteel poverty — or is this gentile poverty?

I used to worry that one day I would end up living alone in a cold room, a blanket around my shoulders, eating baked beans from a tin by candlelight. And now that day has arrived, you know what? Baked beans taste better cold.

A lot of my journalistic and artistic friends are in the same boat — and we’re all sinking fast. We make nervous jokes about being poor and boast about what we’re going to have to cut back on next. “My throat,” said one friend. Of course, compared to the long-term poor, I’m not — we’re not — poor or really suffering at all. (The real poor are always stuck in a cost-of-living crisis.) But poverty is relative and just as people like me have become the Relatively Poor, so others have become the Relatively Rich. People like my friends who before the cost-of-living crisis didn’t appear rich, just well-off.

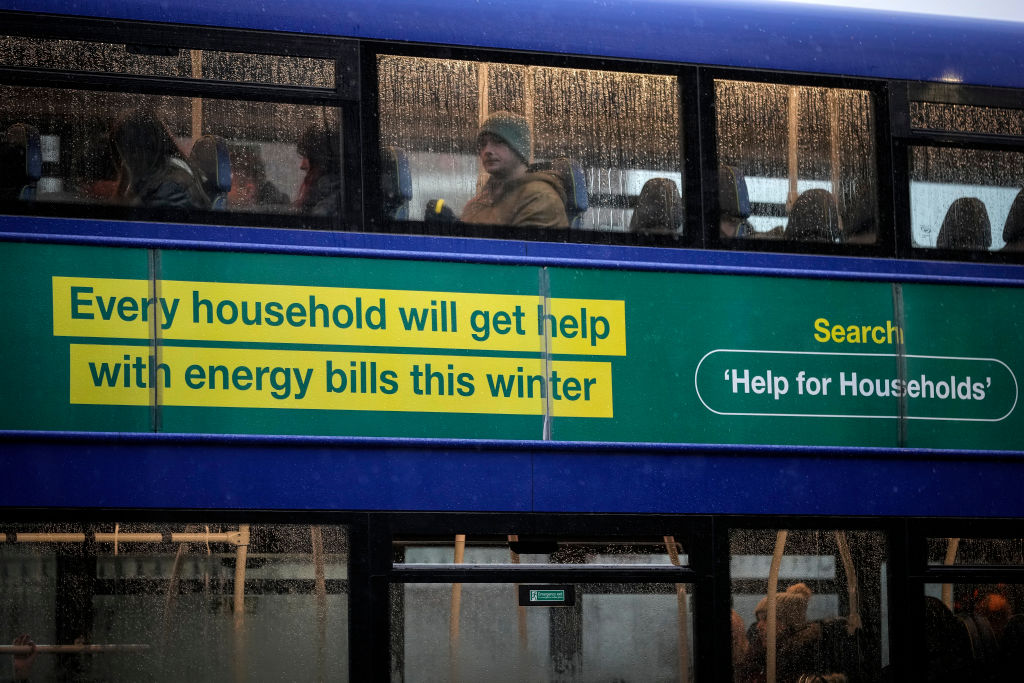

The gap between the Relatively Poor and the Relatively Rich is not about property, income, luxury items or lavish lifestyles; it’s about the uninhibited use of basic things like electricity, gas and the purchase of essentials like food and clothing.

Now when I visit friends, I’m immediately struck by the fact that their homes are… warm. I used to envy their lovely holidays, but now I envy their lovely central heating. And I never noticed this before, but they have kitchen floors that give off heat. Hot floors, imagine! And here’s the thing — they don’t care about the cost of all this warmth. It’s this freedom from worry that is the great luxury enjoyed by the Relatively Rich.

There are other key domestic differences between us. There is a sound you will hear only in the homes of the Relatively Rich: it’s that whirling metallic hum of a tumble dryer in action. And what a beautiful sound it is! To save money I put my clothes out on the drying rack — and wait five or six days — but they’re never dry; they’re just less wet.

My new relative poverty has had a terrible effect on my dating life. It’s demoralizing going on a date in damp underwear, moist socks and a stained suit (dry cleaning is another cutback I’ve had to make). I can’t afford drinks or dinner so I take dates on walks in the park and we sit on park benches talking through chattering teeth. I don’t blame the UK government, Putin, the energy companies or the structural iniquities of capitalism for my sorry state: I blame me. If I had led a more industrious and disciplined life, instead of the hedonistic existence of a louche lounge lizard, I’d have saved enough money to keep the heating on and carried on taking hot baths when tough times arrived.

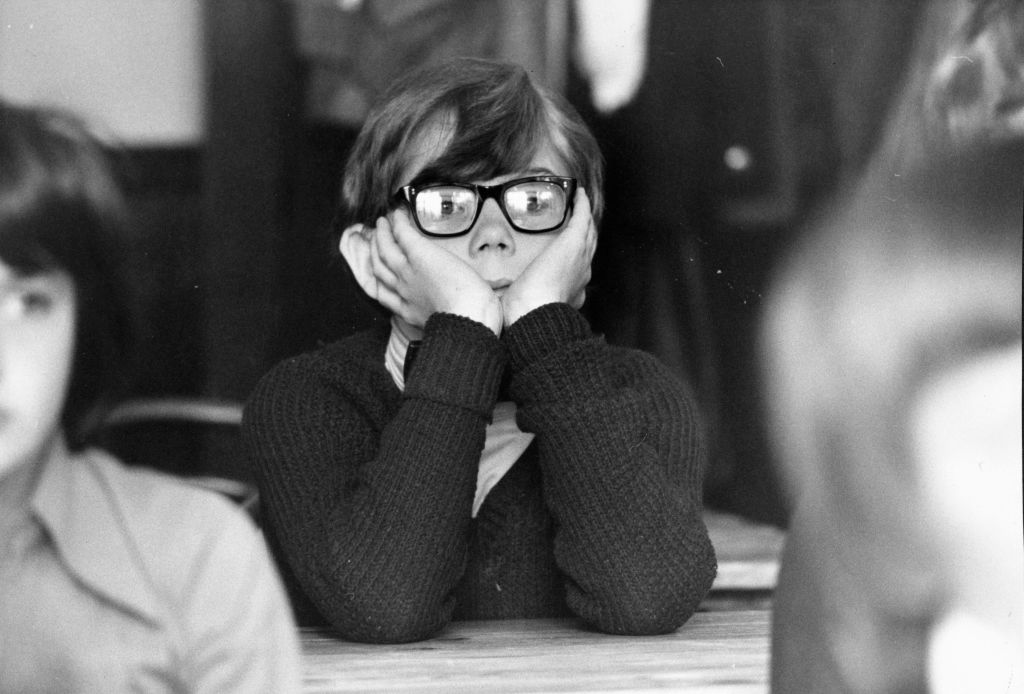

But when young I thought I was being so hip and cool in avoiding the conventional middle-class conveyor belt of university, a proper nine-to-five, well-paid job, climbing up the career ladder, working your nuts off and saving for a rainy day, like my peers did.

I can remember being in my twenties and, instead of working, spending long afternoons in the arms of beautiful smart women, drinking cold martinis and having hot sex and feeling sorry for my hard-working friends. “Those poor suckers,” as I’d dubbed them — stuck in offices and going to business meetings.

Back then we arrogant bohos mocked the bourgeois pettiness of the financially prudent and sneered at sensible savers, with their talk of pension pots and having a financial adviser. Now I fear it is too late for me to become one of them. I’ve made my bed and will have to shiver in it.

Bohemian London is full of men like me. Men who now depend on the kindness of friends for life’s little luxuries. They are charming and amusing men with stained suits and shabby smiles. Dedicated dilettantes, they dabble in the arts and literature. They float around the city and like to think of themselves as flâneurs — instead of mere failures. That old brave twinkle in their eyes has been replaced by something new: fear.

And yet despite my worries and discomforts, this period of relative poverty has been instructive and taught me to appreciate the basics of life — central heating, the hot bath, the warm towel — that I took for granted. Now that they’re gone, they never seemed so glorious. How I envy the Relatively Rich.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2023 World edition.