On December 5, 1933, exactly ninety years ago, the Eighteenth Amendment was repealed, formally lifting the ban on alcoholic beverages that defined the Roaring Twenties. Of course, that wasn’t the first time someone tried to outlaw the world’s most popular drug, but it’s probably the best-known case study where the contrast between intended results and reality reached absurd extremes. And yet, the best part of a century later, the same mistakes haunt us.

Saloons had a reputation as pretty rowdy places, filled with whores, card playing and drunken cowboys. The Anti-Saloon League formed to shutter these dens of sin. The League’s leader, Wayne Wheeler, who spearheaded the movement towards Prohibition, told different parties what they wanted to hear. He told the Progressives that drinking was a vice of the poor. He told bigots that immigrants, stepping off the boat at Ellis Island and crowding into squalid slums, were corrupting American values. Wealthy industrialists such as Henry Ford wanted a sober workforce, and early feminists feared the man of the house stumbling home drunk each night. A convergence of these factors led Congress to pass the Eighteenth Amendment in 1919, banning everything from light beers to absinthe.

But who didn’t fancy a tipple? Though fewer Americans overall may have been drinking, the contents of their glass became much more toxic. Like today’s meth labs, clandestine distilleries were set up in the sticks brewing bathtub gin. Hard spirits were favored over beer, as smaller volumes were easier to transport. “Jake ginger” was an alcohol-rich medicine that was mixed with chemicals to hide the taste and sold on the black market, where the cocktail may have left up to 100,000 victims with crippling nerve damage.

Sometimes, industrial alcohol was re-diverted. Bootlegger George Remus ordered stockpiles through his front companies, then hijacked his own shipments. While he was in prison, his wife ran off with a Prohibition agent. On his release, Remus ran her off the road and shot her dead. Representing himself in court, he was found not guilty by reason of insanity.

There was a growing atmosphere of lawlessness. Despite the image of barroom brawls and Wild West shootouts, most saloons were peaceful places. That all changed under Prohibition as trilby-wearing hoodlums sprayed each other with Tommy guns. The national murder rate climbed from 6.5 per capita in 1918, to 9.7 by 1933, as rival mobs clashed over the liquor racket.

At least 286 civilians were officially slain in liquor raids, but the true figure could be in the thousands. In one raid, agent William Turner shot dead an unarmed man hiding behind a rock holding a half-gallon jug of whisky. The Prohibition Bureau was undermanned, underfunded and with all the cash floating around, utterly compromised. Since bigshot beer barons could afford to pay off the feds, it was usually poor, small-time rum-runners who got caught. Mrs. Etta Mae Miller from Michigan, a mother of ten, was given a life sentence after being caught with her fourth bottle of hooch. By 1930, half of all prisoners were serving time for booze.

By the time Prohibition was repealed, the war on drink had mutated into the war on drugs. Morphine syrup and cocaine drops were once a casual, everyday indulgence, but after the passage of the 1914 Harrison Act, the doctors prescribing them could be stripped of their licenses, and the tens of thousands still hooked morphed from patients to junkies. After his clinic was shut down in Portland, Oregon, one doctor asked if there was anything he could legally do. He was told to throw his patients in the sea, since fish food was all they were good for.

We’re still dealing with the consequences of that now.

The Mafia may have dressed more dapper than your average crack pusher in the movies, but they were just another gang with great marketing. The Godfather spread the myth that the Mob didn’t do drugs, or at least had reservations. But once they knew Prohibition was over, it was a smooth transition from bootlegging to drug dealing. Some of them, like Arnold Rothstein and “Lucky” Luciano, were running dope already.

“The Mafia was looking for their next moneymaker before Prohibition even ended,” says Seth Ferranti, director of the documentary Dope Men. “Bootlegging had turned the Mob from a mom-and-pop level organization to a corporate-type entity, and they knew that narcotics was the next big moneymaker.”

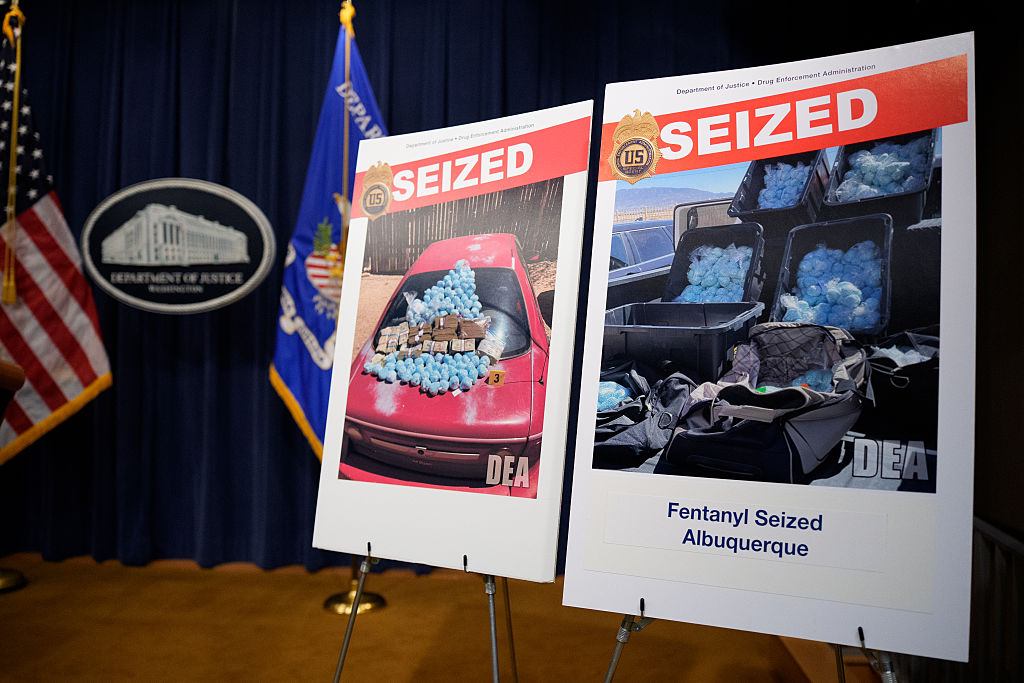

Once their heroin pipeline from Europe was smashed and federal indictments brought the crime families to their knees, the Mob stopped being major players in the drug game. But we’re still seeing the same problems from Prohibition playing out today. These days, Mexican narcos dominate the meth, opioid and cocaine rackets. Again, they had a ready-made client base: from 1999-2011, OxyContin prescriptions jumped sixfold. When Oxy started being taken off the shelves, tens of thousands of Americans were still hooked, so now where could they go? Like the bootleggers of the Twenties, the Mexicans realized that smaller, densely-concentrated shipments were easier to carry across borders, and now heroin, once depicted as a bleak, soul-destroying drug, appears almost quaint held up next to fentanyl, fifty times as powerful as your grandpa’s smack, and “tranq dope,” a deadly drug cocktail with no known antidote. Like jake ginger or bathtub gin, these are the product of our modern-day prohibition, which has willingly given up control of these poisons to the criminal element.

Although the cartels themselves (largely) refrain from the sort of bloodletting seen south of the border, the street crews who handle distribution terrorize the inner cities — a gangster subculture sustained by peddling dope, i.e. neo-prohibition. Law enforcement arm themselves accordingly, and their overzealous attempts at policing the nation’s bloodstream in “no-knock” raids, where heavily-armed SWAT teams burst through your door unannounced, leave dozens dead each year, including many innocent residents, children, pets and officers themselves (this is besides the hundreds of other police shootings of drug suspects). Meanwhile, recent scandals, from accepting payoffs from mobsters to cleaning cash for Colombian coke barons, have shown the DEA to be just as compromised as its predecessors in the Prohibition Bureau.

To date, the Eighteenth Amendment is the only one to have been repealed after its catastrophic consequences became obvious. But alcohol prohibition only lasted thirteen years, while the war on drugs has raged longer than a century, with little to show for it except an overdose crisis, which now claims more lives each year than every fallen American soldier since World War Two put together.

Leave a Reply