I first visited the Greek monastery of Agios Stefanos on the rocks of Meteora in the early spring of this year, one week after my baptism into the Orthodox Church. Greece was heavy with Great Lent fasts and preparations for Christ’s resurrection — Easter. I had just escaped the clutches of an extremely sweet but annoying young tour guide with whom my very Greek now-father-in-law had set my fiancé and me up for a tour of the ancient churches. I wanted nothing to do with this young man in a tour van who sounded like he was reciting words from a tape recorder. Later I found out he was, and had taught himself English by doing so (which is pretty endearing in hindsight).

I have a crippling fear of being a tourist and had lost all patience with the photo opportunities and bland historical platitudes shelled out during our drive to the mountainside. At our first stop, a famous monastery taken over by nuns in 1961, we were told that we had twenty minutes to visit. I informed the tour guide he should go on without me.

Agios Stefanos is an excruciatingly beautiful place, covered in fig trees and roses. The presence of Christ is undeniable. So, naturally, when I shoved through a crowd of people to enter the church of Saint Haralambos, I erupted into tears. Two nuns explained to me later that the reason I had sobbed uncontrollably was that soon after someone is baptized, they are more spiritually attuned and sensitive to the sacred energies around them. I thought I was crying because I couldn’t reconcile how awe-inspiring and gorgeous the church wall icons were with the wild herds of tourists acting like farm animals inside one of the most sacred Orthodox sites in the world.

The young nun who saw me purple-faced and ugly-crying asked if I was Orthodox. I nodded yes and she took me by the arm to a little nun closet outside the church. She told me everything was all right and just started bringing me little gifts: a small bottle of holy oil blessed by their priest, a tiny pin of Saint Haralambos to attach to clothing for protection, chrysanthemum incense, a bookmark with the Jesus prayer on it. Then she took my fiancé and me to the original fourteenth-century church, off-limits to tourists, to show me one of the rocks used to stone Saint Stephen, as well as an icon of Christ whose face was burnt off by Nazis during World War Two.

The nun asked if I was crying with sadness or if I was just feeling the presence of God in the church. I said I definitely felt God but asked how she tolerated people acting so disrespectfully in such a sacred place every day. “So many of the people come here with no spiritual home and they are desperate to bring a tiny piece of something holy back with them. Many of them are hurting a lot on the inside. We pray for them all day and our monastery couldn’t be open without their generosity.”

Her response was so compassionate and graceful that I cried even more. I spent a few hours with her and another nun who spoke no English, so my fiancé acted as our translator. I left later with more wisdom and gifts and they told me to come back and see them again. They even let me take a photo of Saint Mary of Egypt in the no-photos-allowed church, as I was baptized on her name day and she is my favorite reformed whore and desert mother of Orthodoxy.

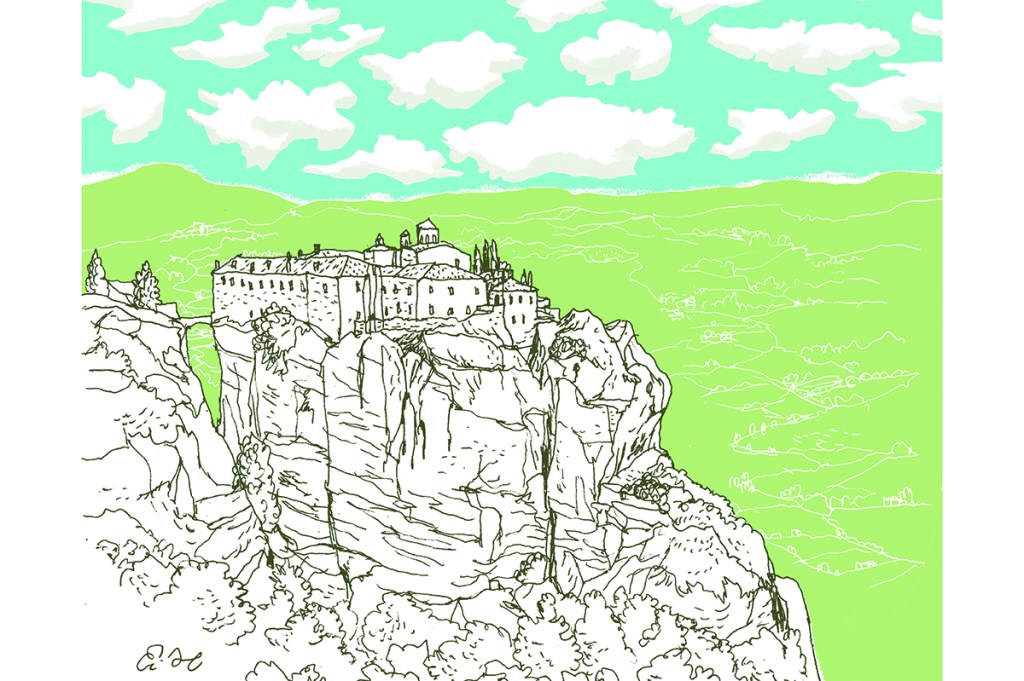

The monasteries of Meteora are famous for the grand and unusual landscape upon which they sit, gigantic rocks that monks have been ascending for prayer and fasting for about a thousand years. There are famous postcards of smiling priests sitting in nets attached to large ropes which pull them to the tops of the rocks. Tourists can drive up to at least four of the six monasteries and then hike up dozens of steep stairs to the churches and monastic dwellings, but at least one is still only accessible via lift or cable car. I do not yet have the Christian faith or strength necessary to travel up a cliff via gondola, so I skip that one. You need not drive up the mountain, though; you can hike through on the exquisite and ancient shepherd trails that lead to the churches above.

The plant life along the forest paths should be enough to convince even the most staunchly Hitchens-esque atheist of God’s existence. Tiny waterfalls and creeks sparkle with the sounds of tiny birds bathing and figs falling from trees into the soft water. Pomegranates, quinces, grapes and blackberry brambles tangle together; cyclamen and poppies cover the forest floor. Death does not exist there. You can even hear little sheep bells moving through the hills. The ruins of old hermit rock dwellings in places no human should ever be able to access are visible from the trail.

Meteora had such a profound effect on both me and my fiancé that in October we returned there to marry, in the thousand-year-old church of the Dormition of Mary that sits beneath the rocks. The famous wall icon paintings, which depict everything from the Theotokos’ dormition (death) to Satan dragging bad souls to hell, are no younger than 500 years. Meteora is the most holy place in Greece, second only to Mount Athos. I invited the nuns to the wedding, and the whole village knew the marriage was happening. We later learned the nuns do not attend weddings, but they still prayed for us all the day of the ceremony.

I returned to Agios Stefanos to see the sisters the very next day and assisted one older nun working the entrance by reprimanding a middle-aged, doughy woman for trying to get through to a tour in leggings so tight that her body looked like it was eating them. I hadn’t even spent five minutes there and was already devolving back into my very un-Christian, impatient and angry self. No amount of praying has yet healed my vitriol for inconsiderate tourists, though I am sure I am one occasionally.

I remembered my first time visiting Agios Stefanos, watching people shove each other for photos even though pictures were not allowed, and witnessing the nuns patiently but firmly reminding foreigner after fo eigner that they could not enter a monastery dressed in ass shorts and would have to tie a long scarf around their waists for modesty’s sake. I had cried so hard in the church that first morning in April that I had to go sit in the corner. I felt the weight of 900 years of liturgies, countless prayers made in the face of catastrophic wars with Nazis and Turks, the same chants recited for centuries, and of course, my Achilles-heel hatred of tourists. I used to cry like that on mushrooms under the stars, but was feeling the same sense of cosmic overwhelm while totally sober.

Visiting the nuns after my wedding, I of course cried again. The trees along the shepherds’ paths were turning blood-orange and yellow, and the rose garden in the church courtyard was in its final full autumnal bloom. This time a different sister told me that the reason I cry so much at their monastery is because I’m an artist and am very sensitive. Instead of being taken to a closet this time, they took me into a refectory and served my husband and me perfect Greek coffee in crystal cups with little cookies and croissants. The sisters said that next time I could come stay with them as a visiting pilgrim. Several of them offered me profound advice about everything from spiritual fathers to… marriage. The nuns may not be married to men, but they take their marriages to Christ very seriously and gracefully. A large icon of Mary Mother of God hung from the wall across from us, and the room’s pristine mosaic floors were baked in a warm gold light. I thought all nuns resided in severe simplicity but was mistaken. The least this monastery could do was surround the graceful sisters in beauty for dealing with all the hopeless and pitiful tourists who keep coming their way.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2022 World edition.