Historically Americans have had little, if any, respect for college and university professors, for whom they felt a mild though distant and tolerant contempt. As more and more members of the professoriat have been recognized as “experts” in their respective fields, or at least at the edges of them, since World War Two, they have naturally presented themselves to the public under the guise of “specialist,” a vast improvement over their previous reputation as absent-minded eggheads barely able to afford the Ford Motor Company’s cheapest product and a shabby house on the wrong side of the railroad tracks.

Eventually many, or even most, of them either left their institutions of higher learning entirely or distanced themselves from them to some degree — usually for the grossly material motives they condemn men of business for having — while growing steadily more present to society as revered public figures. In the process, they came to be regarded less as people possessed of expert knowledge in some highly specialized field and more as public savants and even gurus, to whom journalists and politicians showed reverence by metaphorical acts of proskýnesis, of which the plain people took due note.

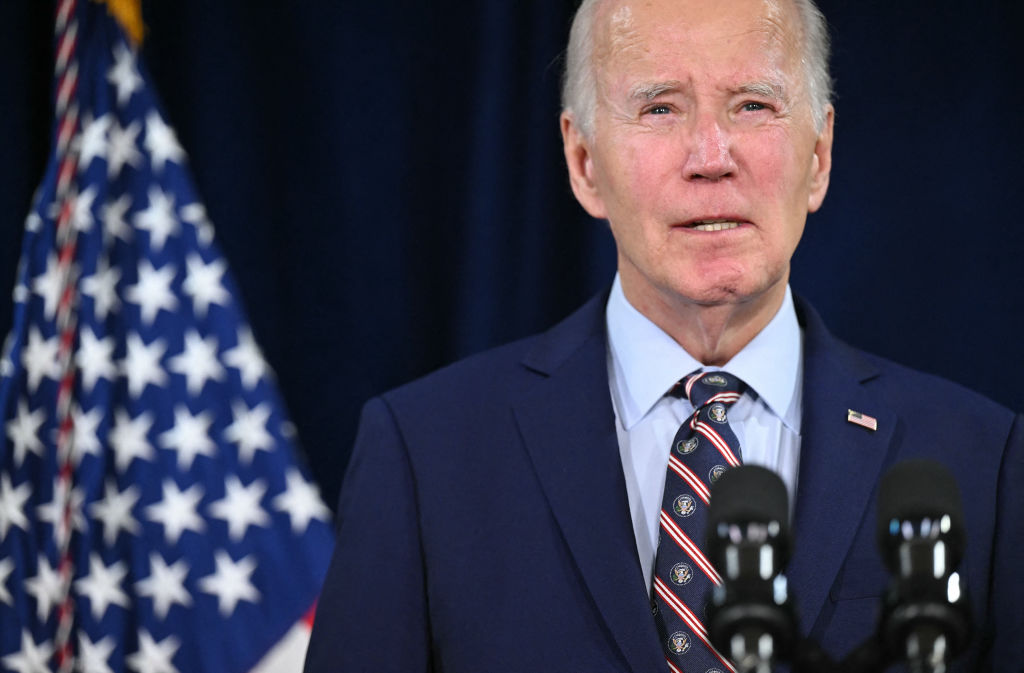

The past two years — in which public affairs in nations around the world have been substantially surrendered into the eager hands of medical and other “experts” — have put an end to that, and probably for good. For all too many people, the names of Dr. Fauci in the United States and SAGE (the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies) in the UK have become synonymous with FRAUD and HUMBUG, unpleasantly recalling the Duke and the Dolphin in Huckleberry Finn and il Dottore Dulcimara in L’Elisir d’amore. Despite having been entrusted with the vast, indeed almost total, power of a Chinese emperor or the leader of the Chinese Communist Party today, they achieved almost nothing positive in their management of the Covid-19 pandemic. In fact, recent reviews (admittedly, by other experts) of their performance indicate that many of their policies for containing the virus — the infamous lockdowns especially — contributed significantly to increasing the number of fatalities, while coming close to destroying the global economy in the process.

Webster’s New International Dictionary (Second Edition) defines “expert” as “one instructed by experience… one who has special skill or knowledge in a particular subject, as a science or art, whether acquired by experience or study; a specialist… One is an expert whose knowledge and experience make him an authoritative specialist.” As with so many things in the modern world, mass democracy, which is inherently inflationary, and mass education have inflated and cheapened the meaning of the word by extending it to include anyone who holds an academic degree in a particular subject, no matter how small its intrinsic importance may be, and has exploited it to make a name (and often a small fortune) for himself from it — indeed, to anyone who has written a book or books on any subject at all. I myself have published works on, among other matters, the history of American immigration policy and of democracy in the modern world. I do not, for that reason, consider myself an “expert” in either of these fields; I simply have read and written widely in them. (Were anyone to accuse me of being an “expert” on either subject I should probably throw myself in front of the next Burlington Northern Santa Fe locomotive highballing it through Laramie.)

“Expert” is not only a largely meaningless, or at least inaccurate, word. In most instances, it fails also to recognize the difference between learning and practical experience. Consider, for instance, the case of Dr. Anthony Fauci, currently chief medical adviser to the president of the United States and a physician-scientist and immunologist serving in the capacity of director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. It is obvious, considering that Covid-19 is the first catastrophic pandemic to occur since the Spanish Influenza killed 55 million people in 1918-20, that the good doctor has vastly more professional knowledge of how viral infections infect human populations than he has experience in preventing a pandemic from spreading among complex modern societies and managing them by political and bureaucratic means when they do. Herbert Hoover, the civil engineer, humanitarian, and director of Belgian relief during the Great War, would probably have made a far better job of it.

Further, “experts” in the more practical, direct and humble work in wide and varied fields like medicine itself are nearly always honest, modest and down-to-earth people, and recognized as being so by their patients. Once they resign from private practice and enter government service as highly paid bureaucratic “experts” and de facto politicians, however, they become a very different animal. For a time, perhaps a prolonged one, the difference does not show. Sooner or later, it does show — whereupon the Faucis of this world are tarred and feathered and ridden out of town on rails, having shortened the word “specialist” from a ten-letter word to a four-letter one.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2022 World edition.