I would do anything to help a friend. Need money? A shoulder to cry on? A place to stay? A confidant to confess to? I’m your man. Want me to read your new novel? Forget it. I would do anything for a friend, but as the late Meat Loaf would say: I won’t do that. Sorry. I’ve been there. Read that. And I’ve had enough.

Many years ago a really good friend showed me his first novel. It was so bad it left me speechless — but I had to say something. So I did the only thing a good and trusted friend could do: I lied. “It’s really funny and smart!” I said.

Since then he’s written four novels, all self-published and each one worse than the last one. And every time he asks me for my opinion I say, “smart and funny” or “funny and smart.” He’s happy, I’m happy.But then last week he asked me what I thought of his latest novel and something inside me cracked and out popped the truth. “I’ve got to be honest,” I said. “It didn’t work for me. It just wasn’t…”

“Smart and funny?” he said.

“Yeah. I fear so.”

He’s not returning my calls.

I love my friends. Many of them are very talented — and some are very deluded about their talent. But I’m tired of being the good, supportive friend who schleps out to their exhibitions, private screenings, launch parties and public readings. Thanks to social media we’re expected to praise our friends for everything all the time.

But what if you don’t like what they’ve done? Telling a close friend his novel stinks is like telling him he has bad breath. It’s embarrassing. I’ve always wondered what Martin Amis and Christopher Hitchens did whenever their good friend — the late and brilliant critic Clive James — published another one of those bad novels of his? Did Mart and the Hitch think: Jesus, what are we going to say to Clive? Best stick to the old funny and smart line. Yeah, let’s do that.

This is a problem not just for people with writer friends but creative friends in general — artists, dancers, photographers, musicians — who all claim to want your “honest opinion” of their work and then are horrified by your honesty. Be warned: friendship is the first casualty of truth.

So what do we do? Lying is a popular option. It’s caring and convenient. But what about personal integrity and critical honesty? Isn’t it kind of patronizing to pat a friend on the ego and pretend you like what they’ve done? Well, it depends on what matters most to you, your opinion or your friendship.

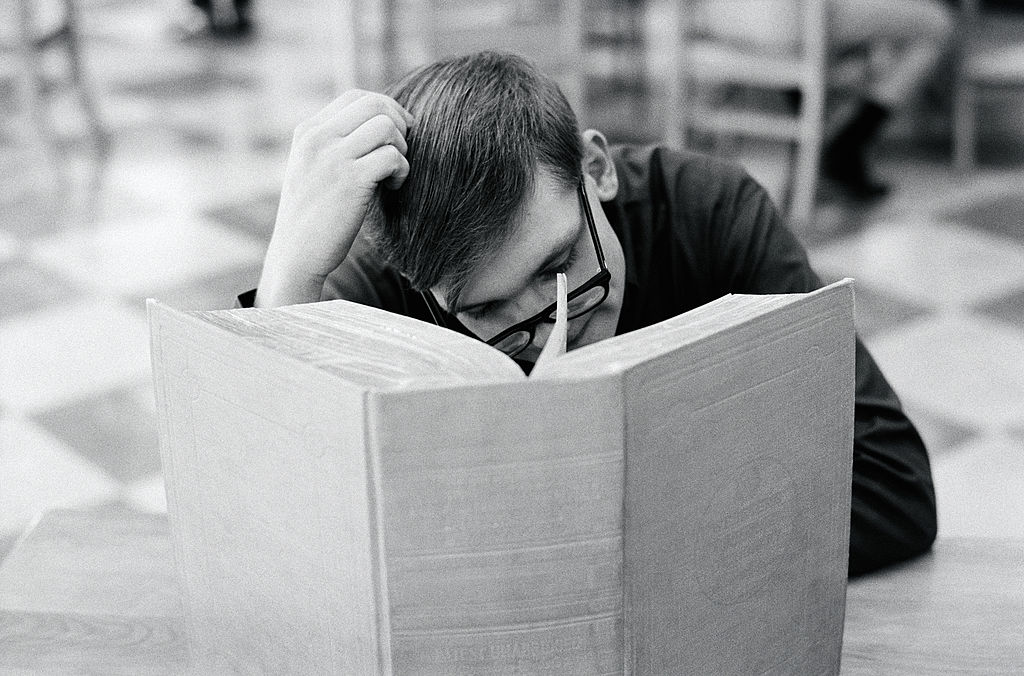

Novelist friends are a particular nuisance because novels take so long to read; and literary novelists are so touchy about their work. Why do they still write novels? I thought this was the age of the essay, the memoir, the blog or the Netflix series? I remember when people talked about the Death of the Novel. (If only!) Then it was The Death of The Author. (Ha!) Everyone I meet these days is an author or struggling to be one.

Don’t they know that writing a good novel is really very hard to do — and that’s why God created journalism! It’s for lazy people like me with a limited talent and a short attention span. It was the legendary journalist Tom Wolfe who said the novel was redundant — and then wrote a smash novel, The Bonfire of the Vanities. Traitor.

Since then, it’s become de rigueur for journalists to write a novel. It’s the literary equivalent of losing your virginity. But people who write novels are masochistic. You spend years writing it, friends blurb it, we all have to buy it, read it, praise it — and in most cases it disappears without a trace. I tell young friends: when the urge to start a novel appears, go into a dark room, lie down and breathe deeply until it passes.

Even if your good friend’s novel is really good, you feel bad because it’s good; and if it’s really bad you feel good (schadenfreude). And then, on reflection, you feel really bad because they got their bad book published and your good book remains unpublished — as I know all too well.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2022 World edition.