Can one egregiously bad scene ruin an otherwise great movie?

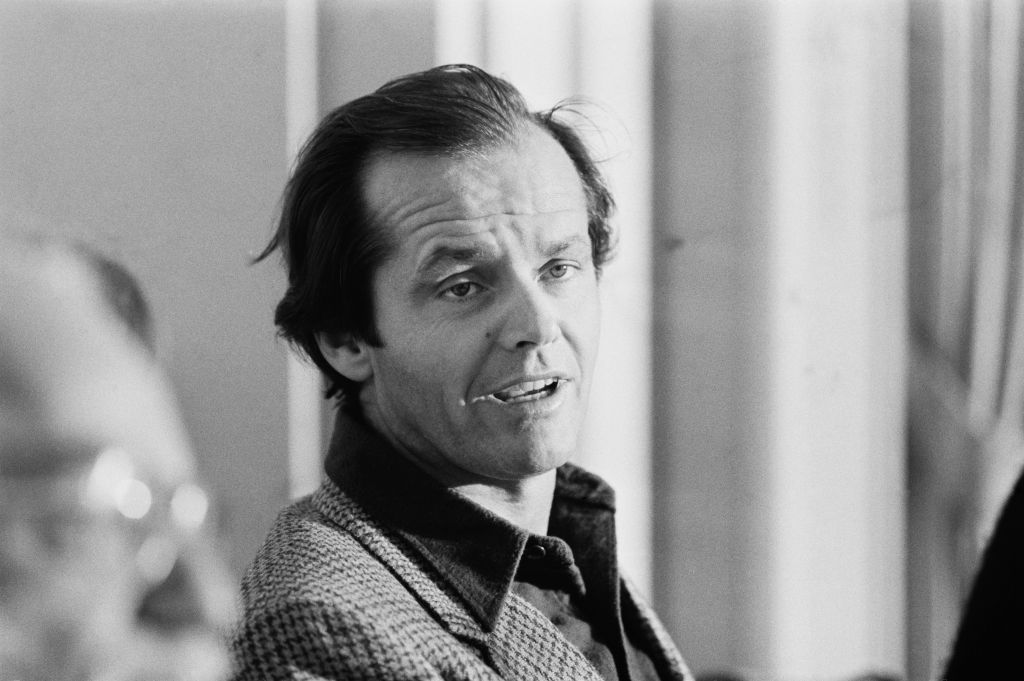

When I go on an early 1970s jag — revisiting the golden age of American cinema — I can never bring myself to rewatch Five Easy Pieces (1970), in which Jack Nicholson plays an upper-middle-class piano prodigy turned downwardly mobile oil field worker. It’s a fine character study poisoned, for me, by the famous scene in which a petulant Nicholson berates a diner waitress who stubbornly refuses his request to add tomatoes to his omelet.

I’m not sure how screenwriter Carole Eastman intended this to play, but critics at the time hailed it as a voice-of-a-generation moment, a symbolic middle finger to the establishment — as if a harried working-class gal was a plausible stand-in for IBM, the Selective Service and Richard Nixon. (Nicholson ends the encounter by angrily sweeping glasses and silverware off the table, a clichéd action that happens with ridiculous frequency in movies but which I have never witnessed in real life.)

From the same era, Sam Peckinpah’s beautifully elegiac western Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973) — the one with “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” and a score by Bob Dylan, who plays an enigmatic knife-thrower named Alias — breaks its mood with a sore-thumb episode in which the compromised lawman Garrett (James Coburn), taking a break from pursuit of his erstwhile friend Billy, frolics with five whores. (Thank God this is The Spectator so the w-word won’t be replaced by the Department of Labor-laundered term “sex workers.”) According to Peckinpah scholar Paul Seydor, the cast and crew begged the director to tone down this stupid romp, but Peckinpah, master of the balletic bloodbath, stuck to his guns.

William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), a deeply affecting account of the readjustment problems of returning World War Two veterans, makes a cheap political point in a diner scene in which a vile boor badgers a handless vet (played by Harold Russell) for his sacrifice. The rude creep — who bears a possibly noncoincidental resemblance to Thomas E. Dewey, GOP standard-bearer in 1944 and 1948 — is Hollywood’s idea of an “isolationist”: that is, someone who prefers the US to stay out of foreign wars. Written by playwright and FDR speechwriter Robert E. Sherwood, this depiction fits into a deplorably long national practice of caricaturing Americans who oppose any of our many wars as beady-eyed enemy symps rather than pacific patriots who have a sincere disagreement with government policy.

The ultimate I-dread-what’s-coming-next scene comes toward the end of another 1946 classic, It’s a Wonderful Life, when, against Clarence the Angel’s wishes, George Bailey (Jimmy Stewart) sees what would have become of his wife Mary (Donna Reed) had he never lived. Any sentient viewer suspects that Mary would have wed the cretinous millionaire Sam Wainwright, who’d have spent his adulthood dallying with floozies and wearying Mary with his inane “yee-haw” greeting. But no, in the film her unspeakable George-less fate is… to be a spinster librarian!

I cannot watch this — though I do every Christmastime — without cringing, though there is an excellent essay by an Idaho writer named Clare Coffey making the case for its aptness. Look it up.

Oh, and George Bailey also does the table-sweeping routine, destroying in a fit of despair the model city he has meticulously constructed as a miniature reminder of the life he might have lived. Filmmakers of the world, I beg you: enough of this mensal madness!

The crude racial stereotyping in 1930s and Forties films is often squirm-inducing. I know there is a defense of the bowing-and- scraping actor Stepin Fetchit as a trickster figure, but that seems a reach. (Though he is an essential part of the 1934 John Ford-Will Rogers gem Judge Priest.)

As an undergraduate long ago I heard the Marxist-feminist scholar Elizabeth Fox-Genovese lecture provocatively on the oft-mocked performance of Butterfly “I don’t know nothin’ ’bout birthin’ babies” McQueen in Gone with the Wind (1939). I wish I recalled the gist of Professor Fox-Genovese’s argument, but I’m afraid that memory is gone with the brain cells. For all the modern handwringing about Gone with the Wind’s romantic portrayal of the antebellum South, the heart of the film remains the performance of Hattie McDaniel as Mammy, the O’Hara family’s house slave — and, in Margaret Mitchell’s very good novel, the only character for whom Rhett Butler has total respect.

I expect streaming-service censors can’t wait to erase Hattie and substitute in her stead an AI-generated robo-actor who talks like a 2024 USC film school student. In the meantime, otherwise talented filmmakers are inserting tone-deaf or eye-rollingly “woke” scenes into their work. But I suppose that’s why fast-forward was invented.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply