I now find resorts more fun out of season. Civilized tourists are as rare as an intelligent Hollywood movie, so local talent will do nicely, and to hell with the vulgar jet set. Gstaad is perfect in June and July, March and April, as are St. Moritz, the Ionian Islands and Patmos, my next destination. Once upon a time the French Riviera was a must, but now it’s a sweaty hellhole, a shabby place for not-so-sunny people.

Although I spent my youth on the Riviera, I was two going on three in 1939, the time I would have chosen to be an adult had I been given the choice. Old hands there used to tell me about that summer, the gayest — in the old sense of the word — on record. Back then Monte Carlo was still Ruritania-by-the-Sea, and whispers from late revelers about columns of troops between Cannes and Monaco had replaced the latest gossip. Even better were the tales of German spies being put ashore from submarines at Cap Martin and showing up at the casino in dinner jackets. But nothing could put a damper on the fevered atmosphere of fun. People were anxious to have a final fling before war broke out.

On the day in August when the Soviet-Nazi pact was announced, pandemonium broke out on the Riviera. Hotels and villas emptied in hours. Officers and men on leave left within half an hour. The main Monaco casino struggled on but most of the croupiers, as Frenchmen, were called to join their units. An international tennis tournament was canceled, as were the boat races. The high-class tarts who frequented the high-stake gamblers gathered at the Hôtel de Paris and consoled each other. Monte Carlo had never before seen the like: a town full of hookers and a few very rich but very old men, and nothing else. Everything shut down. Then came May 1940, and hectic attempts were made by Brits, including Somerset Maugham, to leave the coast via Monte Carlo. Some ultimately reached England.

The ax fell when Italy declared war on a rapidly collapsing France and the Italians walked from their border into Monaco. Even worse was the embarrassment when the Italian troops were cheered to the rafters by the Italians of Monaco. After a temporary shutdown, the casino reopened and posted unprecedented profits as rich French Jews and other refugees reached the principality once Prince Louis declared Monaco a neutral sovereign state. This suited everyone, including the eventual occupying German army.

Twelve years after the end of the war, I walked down to the old Beach Hotel and the Sporting Club with a gentleman who owned them, a certain Aristotle Socrates Onassis. He knew my dad and was nice to young Taki. Onassis became a household name during the early 1950s when he “bought” Monte Carlo. Actually, what he did was become the majority stockholder of SBM, the company that controls the Monaco casino and its biggest hotels. Onassis wanted to keep Monte Carlo a tiny island of old-fashioned charm, but the ruling Prince Rainier wanted a Las Vegas by the Med. Rainier, who looked just like any concierge in his principality, won by issuing more stock and turning the golden Greek into a minority holder. The result, seventy years later, is that the Grimaldis are among the richest families around, and Monte Carlo is an overbuilt, overcrowded cement hell out of a Hieronymus Bosch painting.

St. Tropez was slow to follow the rest of the Riviera, but even there the unacceptably vulgar have prevailed. Rich Arabs and, until this year, rich Russians have turned the once peaceful fishing village into a nightmare. Superyachts, as those monstrosities and super-polluters are called, have turned the main strip of the harbor into a freak show, with masses of sweaty, semi-nude voyeurs ogling fat slobs eating and drinking with their whores on board. Very ugly people own very ugly boats, my old daddy always said, but fortunately he never saw today’s yacht owners. Come to think of it, another great man long gone said exactly the same thing, one Gianni Agnelli.

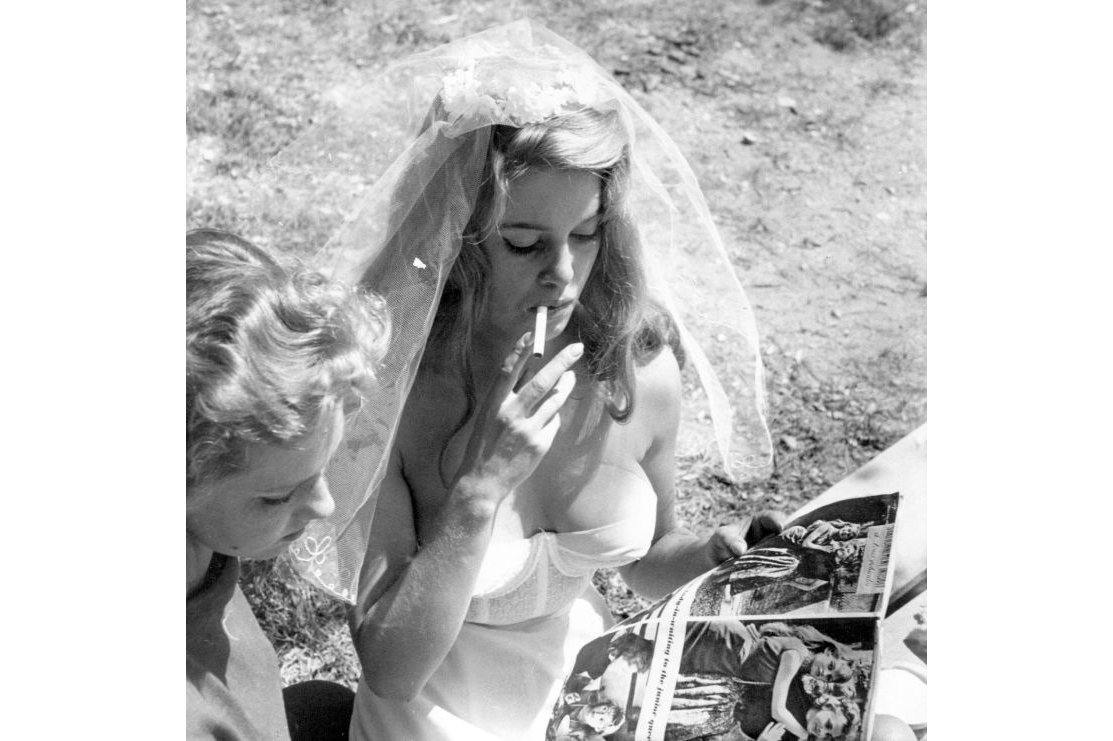

Oh dear, we are getting nostalgic yet again. I’ve just finished Anne de Courcy’s Five Love Affairs and a Friendship: The Paris Life of Nancy Cunard, and memories of the French capital returned stronger than ever. I’ve read many of de Courcy’s biographies, and this one was as good as any, except that I’ve never been attracted to nymphomaniacs, especially rich, bullying, left-wing nymphos like the Cunard dame. (The degree of difficulty in seduction is very important — to me, at least.) What rang my bell was reading about the Noailles. The Vicomte and Vicomtesse de Noailles were as upper crust as it gets and noted patrons of the arts. Marie-Laure de Noailles had the artsiest salon in Paris and was close to Cocteau, Dalí, Max Ernst, Man Ray, Picasso and so on. The Noailles’s palatial house had Dalís, Goyas and other greats hanging on its walls. This was in the 1920s. Around 1965, I was invited to the Noailles’ by Raoul Lévy, the man who discovered Brigitte Bardot and was after young Taki. (I don’t swing that way, so he was slightly disappointed.) But I met Marie-Laure and enjoyed myself talking to her. A crushed automobile by César was in the entrance hall. (Lévy committed suicide later on, but not because of young Taki.)

And so it goes. Memories of grand times in grand places that are no longer fun.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2022 World edition.