“Will someone steal my coat?” “No, you’re on a holy pilgrimage,” my son’s Irish carer-companion Rosemarie reassured him. We were going to Lourdes, where in 1858 a poor peasant girl, Bernadette Soubirous, had eighteen visions of the Virgin Mary. At London Stansted Airport I’d lost a tooth. I had a bad knee and an ancient foot injury. Should I not be in a wheelchair myself, instead of being a helper? Our group was BASMOM, the British Association of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta. I was a bit dubious about Lourdes (it was Rosemarie’s idea). Wasn’t the Order full of recusant Catholics who my father, a Knight of Malta himself, always claimed were “interbred”? He’d cited toilet paper rolls playing “Ave Maria” (probably a myth), and as a Catholic child I was familiar with lurid statuettes of Bernadette and the Virgin and “bling” rosaries.

I would be in a hotel with other helpers, Companions, Knights and Dames. We would work in teams at the Accueil, where our guest pilgrims (formerly called “malades”) resided. My son Nicholas (thirty-nine, Asperger’s) and Rosemarie would stay there. My old school friend from the Sacred Heart, high-powered Anna, and her brother, in a wheelchair, go annually.

Due to our plane’s lateness, my team was sent straight to the Accueil to help guests unpack. It was a baptism of fire. Terrified, I overheard the word “hoist.” I was not nurse material. A helper I’d identified as a “Holy Mary” started heaving guests’ suitcases. I did not participate, due to a dodgy back. I finally got to my tiny hotel room well after midnight. I had to phone for a towel.

Due back at the Accueil at 7:30 a.m., I was so anxious I hardly slept. My new nurse’s uniform was impossible to put on and I had to ask an Italian Dame of Malta in the hotel elevator to tie my apron.

We were told to knock on guests’ doors and offer help. Some women, half-dressed, looked discomfited, but I did assist a tall lady with a lovely face, on crutches, by carrying her teacup. Luckily an experienced helper known as Mad Jane came to the rescue and she and I served breakfasts. This was fun, as I met pleasant chatty women who’d had interesting jobs. One recognized my last name as that of a racing motorist killed on Lake Windermere, where she’d spent her childhood. I befriended Swiss Ursula, the only Protestant, whose husband had died of Covid. Despite her liveliness, she was in permanent pain due to a botched spinal injection long ago.

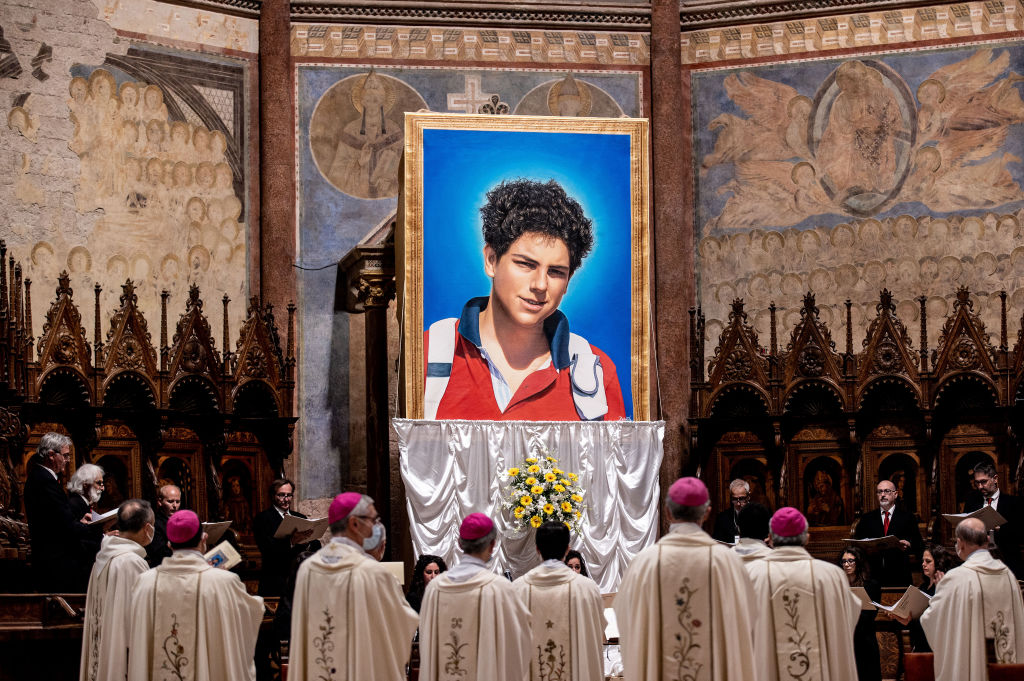

That evening a Catholic widower, a retired psychiatric nurse, escorted me, Rosemarie and Nicholas to the grim former home of Bernadette’s family. Nicholas was awed and Rosemarie talked of Bernadette’s often sad life. She had not always been believed; the mayor built a fence across the grotto where she had seen the Virgin to keep out the crowds. At one sighting the Virgin had announced: “I am the Immaculate Conception.”

Does it matter if one is not a complete believer? I have always found the idea of Jesus being born without his parents having sex hard to swallow. However, after three days, my foot injury disappeared, seemingly forever. My son was happy. I loved hearing snatches of the French Mass at the grotto across the river, and “Salve Regina” sung in Latin reminded me of evenings at school, where I’d made friends for life. I was impressed by the fortitude of our pilgrim guests: the gallant musical boy with MS from a northern town; the young woman with a Stephen Hawking-type voice synthesizer; and Anna’s brother, a calm, comforting presence despite his lifelong impairment.

There were funny moments. In our procession to the grotto in heavy rain, Ursula got soaked and refused to leave the grotto’s shelter, saying it was “un-Christian” to force her out. The “Holy Mary” became very bossy over my tap cleaning and, refilling my bucket, I felt obliged to ask her husband if she’d been head girl of her convent.

A lovely retired teacher’s bag disappeared, so my son’s initial fear was realized. “Forget Jesus, ring your bank!” Ursula advised. A young, ebullient priest sang “La Vie en Rose” on our bus to Bernadette’s aunt’s village, Bartrès, where there was a Mass for anointing the sick. I didn’t think I was eligible, but Rosemarie made sure my son got anointed.

On a serious note, BASMOM, besides helping the poor and the sick, is involved in organizations such as the Nehemiah Project in south London for ex-prisoners.

An old Lourdes hand said that if newcomers don’t “run for the hills” after two days, they usually return. I think I will. My son wants to. Meanwhile, an eighteen-year-old crocodile has given birth with no male input. So perhaps Mary did not use Joseph for that purpose after all.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2023 World edition.