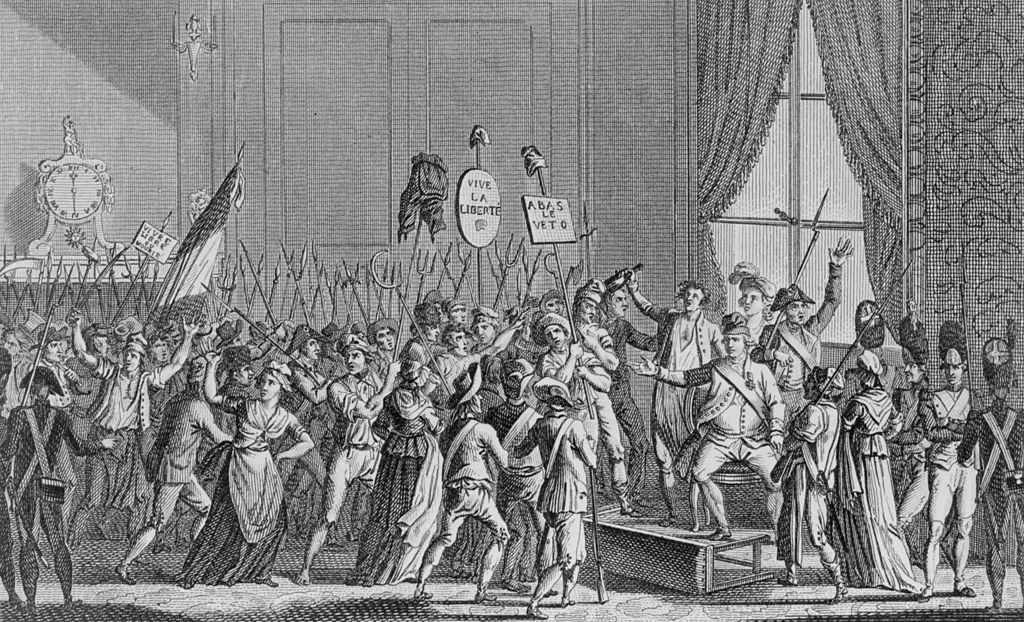

In the first week of October 2022, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, France’s perennial man of the Marxist left, former leader of La France insoumise and present chief of Nupes (Nouvelle Union populaire écologique et social), an alliance of hard-left, left and green parties, invoked the jours d’octobre that commenced on October 5, 1789 with the Women’s March from the Parisian marketplaces to Versailles and ended with the more or less forced departure of the royal family for the capital city in the early morning hours next day after several members of the Palace guard had been decapitated and their heads impaled on pikes. It is unclear what that revolutionary year, and the events of October 5-7, have to do with twenty-first-century France. It’s likely Mélenchon, who according to Le Figaro has a reputation for making outrageous utterances he after- wards dismisses as being all in good fun, had no clear idea himself.

Following the Revolutionary period, and then the Napoleonic era and the restoration of the Bourbons, liberal politics in Europe and North America — despite revolutions here and there, and the revolutionary year of 1848 — were broadly characterized by an institutionalized spirit of positivist optimism. That spirit prevailed before 1914 and largely recovered following the traumatic shock of the Great War. It revived again after 1945 and lasted throughout the Cold War, down to the fall of the Soviet Union. Yet very shortly afterwards it began to weaken and to doubt itself, before succumbing to ideological confusion, resentment and anger.

Since the French Revolution, leftwing politics, as distinct from the liberal sort, have been essentially about revenge, including in Great Britain with the founding of the Labour Party in 1900, an event recently characterized by the Daily Telegraph as an act of vengeance. Then, leftist vengeance meant class vengeance. While it remains so to some degree, it has lately been greatly expanded, complicated and fortified by identity politics, in which class resentments are compounded and confused by innumerable others hitherto unimagined — and some, indeed, almost unimaginable. Most began as aspects of what was called “grievance” politics, which over the past decade or so has matured as revenge politics: the politics of a bitter, irrational, infantile, implacable, wholly gratifying and fulfilling rage. As the Democratic Party has moved rapidly and resolutely leftward over the past six or seven years, the Donkeys’ political agenda has been narrowed and reduced to one of programmatic revenge: “Let a thousand flowers bloom.”

Since the 1960s, the American left (inspired and aided by the agents of leftism abroad, in Europe, South America, the Soviet Union and in China) had been searching for a fundamental, essential constitutional weakness in American society and the American polity that they could develop as a fatal flaw by exaggerating and exploiting it. What remained of the Old Left thought it was capitalist economics. The New Left agreed, but added what it saw as authoritarian capitalist culture. The inventors of the 1619 Project thought they had discovered it in slavery. In recent years Democrats had a brainstorm and decided it was repressive identity politics. As they were also the institutional propagandists on behalf of multiculturalism and mass global immigration, destructive inspiration came naturally to them here. Americans loved capitalism. Slavery had been abolished a century and a half before, and relations between blacks and whites in the United States were improving drastically — obviously so. Many other countries had histories of economic inequality and slavery, including European and American ones; neither was unique to the United States.

Still, these nations continued to exist and even to thrive, despite many of them being less economically equal and socially fluid than the United States. All of them, however, were familiar with the ordinary human resentments, fears, angers and rivalries among the various races, ethnic and economic interest groups, classes and generations endemic to every society in history — including the most basic and longest running of them all, the ages-old battle of the sexes. The new American revolutionists, having tried so many stratagems based on what they saw as America’s “exceptional” sins and vulnerabilities — and failed — decided to begin again with the most fundamental, permanent and obvious of all of them: human nature, with its readiness to believe that people who differ from you also hate you, are directly responsible for your problems, and against whom consequently you should avenge yourself. Naturally, this final stratagem is succeeding and the perpetrators are now well along in their efforts to turn the United States into a multicultural, multiracial, multi-identity beehive in which all the bees, rather than cooperating harmoniously as a single integrated colony, are furiously trying to sting one another to death.

The Beatles, soft, well-intended — gentle, actually — revolutionaries as they saw themselves, created a famous song called “All You Need Is Love.” Real, hard-as-iron, destructive, nihilistic and vengeful revolutionaries know better. “All You Need Is Hate” could be their anthem. Perhaps one day it will be written out and scored. It is already being performed, all over America especially but elsewhere too.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2022 World edition.