In the late 1990s, author Neal Pollack developed an alter-ego character, “The Greatest Living American Writer,” for the McSweeneys website, to satirize a generation of pretentious authors, particularly Norman Mailer and Gore Vidal, as well as macho literary journalists. That character formed the basis of Pollack’s first book, the cult classic The Neal Pollack Anthology of American Literature. The GLAW has since appeared in numerous other publications, left- and right-wing and completely apolitical, surfacing and de-surfacing as the times demand. Now he’s back in The Spectator World, until we get tired of him.

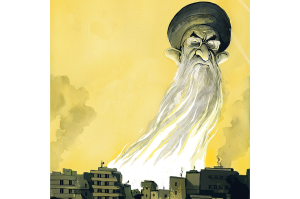

I have been the Greatest Living American Writer across eight decades of world literature and have seen many shocking acts of violence. I was there when Norman Mailer stabbed his wife, when William Burroughs shot his wife and when Michael Chabon said to his wife, “yes dear, whatever you say, dear.” But nothing cuts harder, literally and figuratively, than the stabbing of Salman Rushdie in New York last week. Perhaps now we can all stop pretending that words are violence. Words are not violence. Violence is violence. Words are words. Violins are violins. And never the Twain (Samuel Clemens) shall meet.

The attack on Rushdie is an attack on all writers, but even more so on me, because of my prominence. Like other great literary eminences such as Cheryl Strayed and Bari Weiss, I, too, have stood on that stage at Chautauqua. Admittedly, Chautauqua has never invited me, because they’re afraid of my ideas. But I once bribed a security guard to allow me to stand on the stage, where I delivered an address to an empty auditorium. Technically, someone could have stabbed me, though it was three in the morning.

My heart goes out to Salman and his four families. We know each other well, having worked together on the staff of the New Statesman in London in the 1970s, alongside Christopher Hitchens, Martin Amis, James Fenton, Clive James, James Cliveson, Thomas Hardy, Robert Hughes and seventeen other chain-smoking men who were very proud of their variegated opinions about Marxism. Everyone had their own beats. Salman reviewed novels and wrote about food. I covered homosexuality and southeast Asia, not in that order. Indeed, those were potent times. We loved sitting around the office, whistling at women on the street while playing a game where we substituted the word “Dick” into famous titles of literature. Salman’s best contributions were “Dick of Darkness” and “Dickter Zhivago.” Those were the days, but even then, fear hovered over us, like an angry horse.

“Someday someone is going to stab me in the liver,” Salman said to us one night as we dipped our cigars in Bushmills. “I just know it.”

“Pish posh, old sod,” I said. “You will never be of consequence.”

Well, I was wrong, and then came the fatwa, and global panic. At the time, sales of my novels were declining. I attempted to create my own fatwa by writing a short story where the ghost of the Prophet Mohammed sired a love child with Eleanor Roosevelt while FDR was away at Yalta. No one would publish it, and I instead had to console myself in the arms of my sometime lover, Joyce Carol Oates.

But now here we are in 2022, and the fatwa nearly succeeded. Salman lies in a bed in upstate New York, short an eye and struggling for breath. And we all must make sense of what just happened. It’s clear to me that the world doesn’t value free expression like it once did, when I could call Susan Sontag a “withered old bucket of slag” on stage at Madison Square Garden and get front-page coverage in the New York Post for it. The gender-neutral Twitter police have made it impossible to express such obvious sentiments like “women are women,” “Latinx is not a real word” and “Jonathan Safran Foer is an evil menace who are trying to destroy the world,” all of which are undeniably true.

When the fatwa first appeared in 1989, every writer alive spoke out against it and tried to get onto the stage at a literary benefit thrown by Nan A. Talese and Sonny Mehta. But today, writers have been totally silent about the stabbing. Not a single one has written an article or a blog post or gotten on Twitter to attempt to tie this tragic and unprecedented event to their own flagging and irrelevant careers. It shocks me to my core that no one has spoken out against this heinous and sharp knife-act. My contemporaries are all dead except for the undead Joyce Carol, Don DeLillo and Cormac McCarthy, but all the generations below have proven themselves to be soulless cowards, unwilling to say what needs to be said: that no one should stab a writer before lunch, particularly if they’re not married to that writer.

Mercifully, my dear former staffmate and lesser novelist Salman Rushdie has survived this ordeal. He’s breathing on his own, which is more than I can say for myself, and he’s speaking a few words. When he’s ready to receive visitors, I’ll have my beleaguered manservant Roger drive me over to the hospital in the jitney. Salman will be so glad to see me, and to hear my words of solace.

“Hello, old friend,” I’ll say. “You still owe me money.”