He bore his death sentence more gracefully than most heroes I’ve read about. As the end approached, his columns showed no self-pity or regrets. Meticulous detail was Jeremy’s forte, and atmosphere. Oh, how I envied his ability to convey the mood of a place, the setting that he was writing about. He could replicate a conversation in a pub as if he had recorded it, and it never once sounded made up.

He was the patron saint of the poor but happy. Unlike his predecessor Jeffrey Bernard, who weekly lamented about being broke and ill, Jeremy was the exact opposite, describing his cancer toward the end like a disinterested scientist quoting from a medical case. The first time we met, just after he had begun writing his column, he bowed because of my high ranking in a martial art and called me “sensei” — teacher in Japanese. I laughed and it was the start of a beautiful friendship.

But years before the cruise, his humor and sense of mischief and fun had made me his greatest fan. It began at a Spectator garden party, at which the then-prime minister David Cameron was present. Out of the blue Jeremy produced a bottle of absinthe, the liquor that drove Van Gogh crazy enough to chop off his ear, and was known to have killed hundreds if not thousands. I immediately indulged, so much so that the sainted editor came over like a schoolmaster and warned us about the evils of alcohol.

After a while, and now very much in our cups, Jeremy proposed some coke. Let’s do it, I said and we headed for the bathroom. Once inside a cubicle, we heard someone come in and when we emerged looking worse for wear we encountered a Spectator reader, well dressed, a gentleman, about forty to fifty years of age. He did look a bit shocked, seeing two long-time contributors coming out of a tiny loo. Jeremy did not give it a thought, unlike sensitive ole me. “We’re in love,” I stammered, and Jeremy caught on and planted one on my cheek. The gentleman’s eyes bulged a bit but he said nothing. “That’s a reader we just lost,” said Jeremy.

At a rather pompous dinner I gave when Chiltern Firehouse first opened in London, I took the private room and seated Jeremy and his lady between Leopold and Debbie Bismarck. I was told afterwards that the pair were in stitches as Jeremy commented on life in general. Toward the end, I sat next to him and he asked me not to name the lady with him because “her husband can tear me apart with his bare hands, and he reads you.” I followed his instructions and got a thank-you note from Jeremy, who had begun karate lessons by then. I watched a bit and he was gifted. My only advice to him was to loosen up.

During another Spectator party, Jeremy, Professor Peter Jones and I were outside 22 Old Queen Street while the scrum was inside. By this time, Jeremy had received the bad news about his health but you wouldn’t have known it by the jokes he was telling us. That is when I took him aside and offered to send him to the States where top cancer experts could offer a second opinion and top treatment. He thanked me, of course, but never even contemplated it. He was very English, Jeremy was, and told me he would stick with his oncologist with whom he got along, and so on. I don’t know if going to America would have made a difference, but I do know Jeremy would have felt alone and more of an object over there.

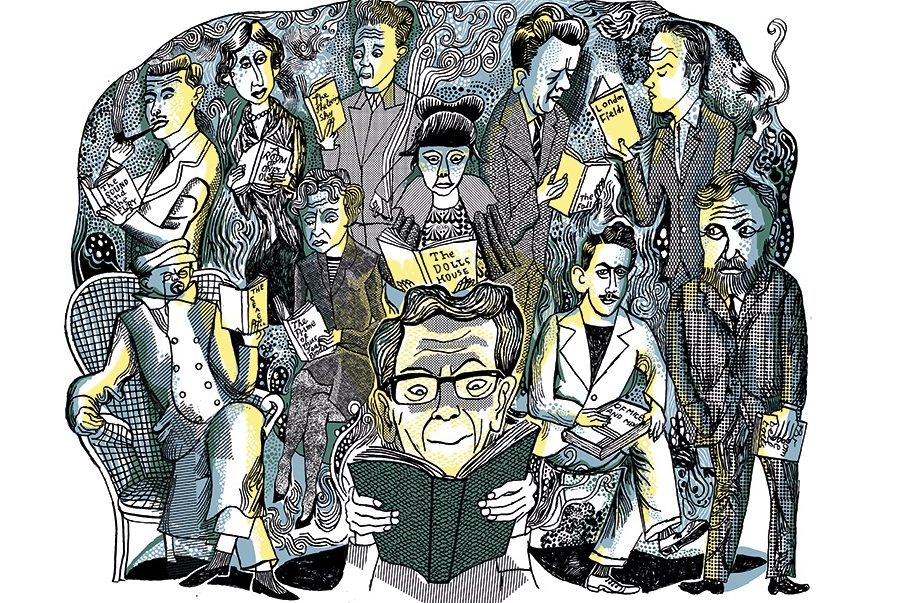

Now on to his writing: at times it was weirdly elegiac yet impersonal, as when he visited World War One battlefields. The pub, however, was his canvas, his ne’er-do-well buddies and fellow drunks the on-the-spot sketches. Jeremy’s rhythm and style were unique as he projected his everyday life on to the page. The prose was muscular, yet sensitive, the brooding happy and carefree. He let it all out and it sounded true. His writing had a physical yet spiritual element. To me, though, he sounded haunted, and I am sure the demons were there — well-oiled but there nevertheless. His was a metaphysical study of pubs, drinking, friendship and self-destruction. He also had the look of suffering about him, however much he tried to hide it with jokes. Were his prodigious powers of recall of drunken conversations at four in the morning made up? Who cares — it was writing at its best.

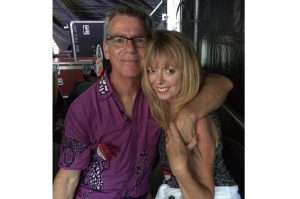

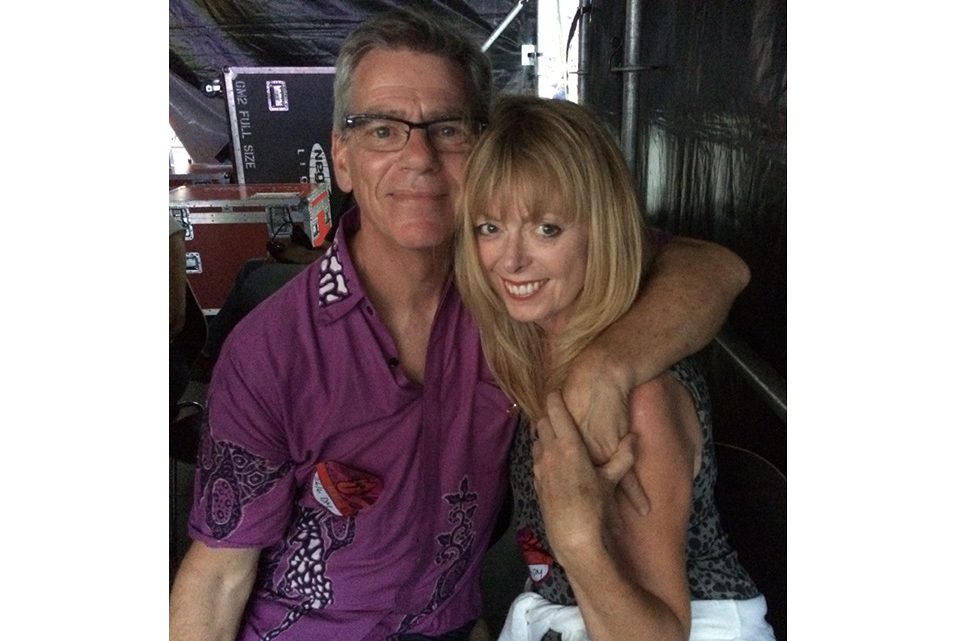

Something else that, to my mind, made Jeremy a unique human being was his magnanimity of spirit. He never once, in all those years, had anything unpleasant to say about anyone. His inability ever to write negatively of others did not extend to himself. I once told him he was saintly, and he gave me a wintry smile and looked embarrassed. The sensory deprivation of pub life and of friends must have cost him a lot towards the end. Thank God he had a good woman like Catriona with him.

I want to finish on a happy note. Jeremy was at his best when describing ridiculous situations, and this one reminded me of the scene where the Marx Brothers squeeze more and more people into a tiny cabin. It is no exaggeration to say that, when I read it, I burst out laughing, then reread it again and again and kept laughing. I will obviously not ruin it by telling the story using my own words, but here are the basic facts: he is inside a tiny loo with his bum against a rickety door that is being pushed by three burly Spaniards eager to do a number two. In the tiny space between him and the loo is a Spanish lass trying to cut some coke and snort it. The men outside are desperate and demand entry while trying to kick the door down. But the Spanish lassie is just as desperate to snort the white powder. She’s having trouble cutting it because it’s hard as a rock and keeps asking Jeremy for all sorts of instruments to crush it with, which he does not possess. On and on he goes, she unable to cut the coke, he begging her to hurry up, the Spaniards driven crazy to get inside. Oh yes, Jeremy also plays the peacemaker trying to appease the Spaniards dying for a you-know-what, and also desperately, but always very politely, telling the lassie to get it over with.

Ten years later I still cannot forget the scene and the way he brought it to life. This is the second time I’ve lost a Low Life colleague, one whom I loved, unlike the former one whom I liked. My bad luck has been that both Low Life writers wrote like a dream. Especially Jeremy. Goodbye, old friend, I shall miss you, and, as we say in Greece, may the earth that covers you be soft.

This article is taken from The Spectator’s July 2023 World edition.