During the best of times, I left New York for gonzo journalism in Moscow; and during the worst of times, I fled a jingoistic wartime Moscow for the post-Covid euphoria of a resurgent New York City.

My life in a sense has come full circle: I left New York for Russia in my freewheeling, bohemian twenties in search of future adventure and returned in my fifties when the rose-tinted dreams of the future that fueled Russia’s hedonistic capital were snuffed out in a murderous rage. That rage of a crumbling empire also engulfed lovely Ukraine in flames, battering its gorgeous capital Kyiv, where I had spent a blissful decade. With two of the three cities that I had called home caught up in a fratricidal zero-sum war, New York is once again King of the Hill.

The urban grime of New York and its ambient violence almost make me homesick for Moscow, where Putin’s minions kept the capital running smoothly with German efficiency. The rampant inflation and frenetic beat of Gotham make me pine sometimes for lovely Kyiv, where nobody was ever in a rush and beer was less than a dollar. I spent a blissful and carefree decade there and would love to visit again.

Moscow in the 1990s was wild and chaotic yet brimming with hope and ingenuity; its challenges and mélange of characters transformed me from a naive slacker into an alcohol-soaked mensch that felt at home in the wider world. I freelanced for the New York Times and was even briefly editor-in-chief of Russian Playboy.

Kyiv in those idyllic years from 2009 to 2014 was a lost paradise. Moscow still set the styles and agenda, but the Ukrainian capital felt suspended in time. Locals joked that it was “five years behind Moscow” but that parochialism had its charms. I fell in love, bought a convertible, and started a business that brought me back to New York often. But eventually Kyiv disappointed me and lost the charms that had made it so special for so many years. I missed speaking Russian in Russophobic Ukraine and so decided to move back to Moscow, my first love in Eastern Europe. Moscow welcomed me back with open arms, and it felt more like home in many ways than Kyiv ever did. It’s a Russian version of New York and feels instantly familiar. But it too broke my heart eventually, in this instance by unleashing terror on its brother and choosing the Soviet past over a modern future. I was glad to have New York to call home again.

In my journey from Moscow to Kyiv and back again, I may have been fleeing unrest, but precisely what made those cities so attractive once were the very reasons for their later troubles.

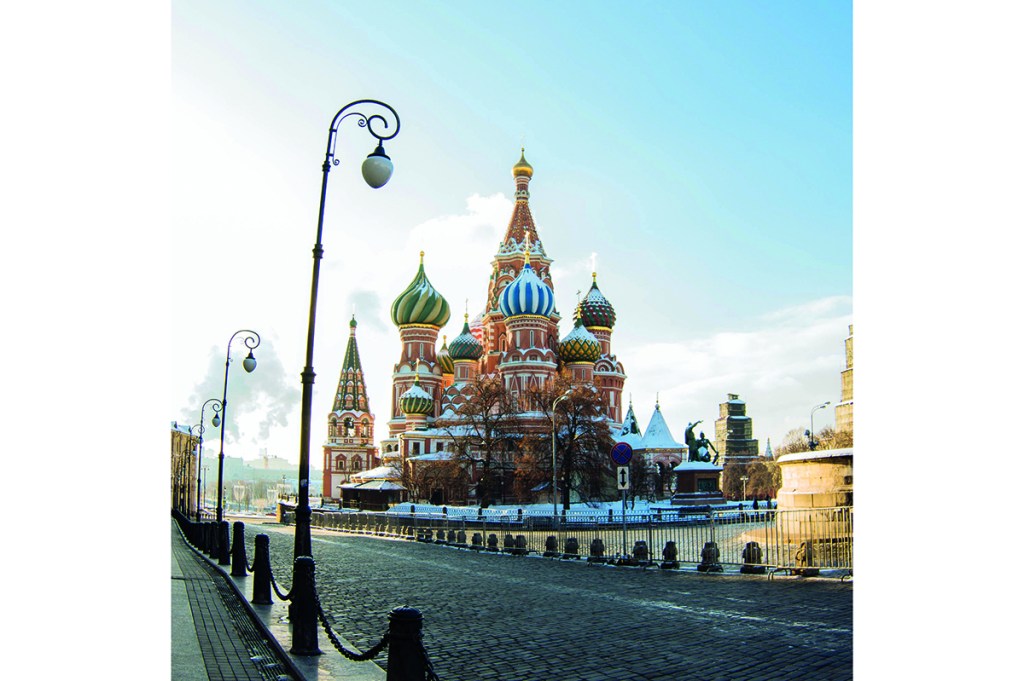

I spent most of my forties in Kyiv and had fully embraced the soulful city with its magical onion-domed cathedrals and winding cobblestone streets on the banks of a lazy river. I had fallen in love, directed a short film, driven across its sunflower-streaked landscapes and hiked the Carpathian Mountains bordering Romania. When the city burst into revolution against the pro-Russian regime in the winter of 2013, I was there cheering along with them for a European future for Ukraine. I sensed even then the imperialist nature of the Putin regime and its need for total control. The Russian government opposed Ukraine joining the European Union and was pressuring the country to join its backwards customs union instead. Russia under Putin had become synonymous with corruption, cronyism and censorship. I too hoped for a better future for Ukraine.

But when Russia annexed Crimea in March 2014 and started a “proxy” war in the eastern Donbas region that was home to the former president, the mood turned instantly from celebration to anger. There was an outpouring of rage against Russia for its aggression, and Russian culture was deemed toxic. Russian artists were banned from performing in Ukraine. Kyiv had historically been a Russian-speaking city where the educated townsfolk spoke Russian and the peasants spoke Ukrainian. That dynamic quickly inverted, and as a Russian speaker I also found my world slipping away. Nobody wanted to converse in the enemy’s language, and I was forced to speak to most in broken English as a tourist would.

My Ukrainian was pidgin, and I was loath to give up speaking a language that I had come to love. Ukrainians also turned inward as they broke away from a common “Soviet” mentality and embraced their own language and culture, suppressed for so long. It was a euphoric awakening for many, but it was alienating for someone like myself who instinctively distrusted nationalism. A racism that was nascent before the revolution also began to manifest itself. I was heckled on the street and told “Turkish go home” and sometimes mysteriously denied entrance to bars and clubs. Foreigners were sometimes dismissed as “sex tourists.” After breaking up with my Ukrainian girlfriend, I had had enough of Ukraine.

I decided to move to Moscow. It sounded crazy enough to shake me out of my breakup blues. I had visited a few months earlier and was impressed by how sophisticated it had become since the dodgy 1990s. There were modern airports and art galleries and landscaped parks with open-air theaters and bike lanes for cycling. It was a lot more cosmopolitan, too, than Ukraine’s capital Kyiv, with Muslims from the Caucasus, Central Asians, Armenians, Syrians, Europeans and others. It was a delicious irony that despite its reputation for racism, Moscow was more welcoming of dark-skinned foreigners than neighboring Kyiv. In a more closed society like Russia, all foreigners were celebrated to some extent. It was a welcome change.

In retrospect, Moscow in those optimistic years was too good to be true. I realize now that Moscow’s global mindset and modern ambitions presaged an eventual conflict with the Kremlin, which increasingly began to fear a “color” revolution like the ones in Ukraine and Belarus infecting the very heart of the empire. A crackdown was thus inevitable. I wonder now whether the war is the final stage of this crackdown, and a great excuse to drag Russians with “European ideas” back to the Soviet Union and its totalitarian mindset that brooked no dissent.

Moscow still felt free when I moved there for good in the fall of 2018, driving nonstop for the almost 600 miles that separate Kyiv from the Russian capital.

Imprisoned Russian dissident Alexei Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation operated from the basement of my friend’s apartment building in central Moscow and harassed the regime with its slick videos of corruption at the highest levels of the Kremlin. The mood in the city was ebullient, optimistic and hedonistic. Despite the ban on gay “propaganda”, Moscow had numerous gay bars and there was a thriving LGBT community. With numerous daily flights to Barcelona and other European cities, the eventual extension of the freedoms of the West to Putin’s dictatorial Russia felt like something inevitable and preordained.

When Navalny was arrested in January 2021 after flying back to Russia from Germany, there were huge street protests in central Moscow with protesters openly calling Putin a “thief” and “murderer.”

The rebellious spirit and the anti-establishment attitude of Moscow’s Navalny generation was inspiring, and I felt vindicated then in having chosen Moscow over Kyiv — and even New York.

The day before the brutal war began in February was a holiday commemorating the “Defenders of the Motherland,” a Russian version of Memorial Day. I spent the evening with some European and Russian friends at a private party celebrating the Russian 1920s, when the burgeoning Soviet Union still held the promise of a futuristic utopia.

The war broke out the next morning and everything changed instantly. The mood went from gay to gray overnight, and fear and horror now stalked the wide boulevards like an enemy. Russia’s Navalny generation howled that Putin had “fucked their future” and, not wanting to be drafted for a mad war or live in a country increasingly resembling North Korea, fled in droves for neighboring Armenia, Georgia or Turkey.

I’m in touch with my Ukrainian friends — some of whom have taken up arms — and have a new respect for Ukraine after their courage fighting the brutal Russians. Unlike cynical Russians that believe in nothing, they understand the value of their newfound freedom as a European nation and are willing to fight to the death to protect their independence. And they’ve united the West, too, in their desperate struggle against the Russian bear.

I often dream these days of Ukraine’s hilly streets and gold-domed churches that appear out of nowhere. But the country’s carefree charm is deceptive: it hides a deep stubbornness and a hatred of Russia that has been slow-cooked over centuries of oppression. Ukrainians had no reservations over smashing Lenin statues and completely severing ties with Russia after the war of 2014. They’re hard-headed and don’t sit well with compromise. I broke up with my girlfriend because she was too stubborn and unyielding at times. And I broke up with Ukraine for many of the same reasons. But it’s that stubbornness that fueled the Ukrainians’ unbelievable resistance to the Russian invasion and has turned them into heroes.

I hope to be back soon, when this war is over, to celebrate their victory with my Ukrainian friends. And this time I’ll try to learn Ukrainian, too. My attachment to the Russian language now feels like an imperial appendage that needs to be excised.

War and revolution have trailed me like banshees during my ten turbulent years in Moscow and Kyiv. I fervently hope that they don’t follow me to New York now and upend everything all over again.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2022 World edition.