On April 26, 1336, the poet Petrarch, accompanied by his younger brother, climbed up the windy slopes of Mount Ventoux in the Rhône Valley. He said that he was the first person to climb that Alps-adjacent peak, which isn’t quite true. But it may well be true that he was the first person to go mountain climbing for fun.

Petrarch wrote about his outing in 1350 in a famous letter called “The Ascent of Mount Ventoux.” The twentieth-century German philosopher Hans Blumenberg (speaking of mountains) wrote that Petrarch’s climb marked “one of the great moments that oscillate indecisively between the epochs,” namely between the medieval world and the Renaissance.

Today, we like mountains. They mean picnics, sight-seeing, natural beauty. “In the mountains, there you feel free,” Eliot wrote in “The Waste Land”. But that feeling is a relatively recent phenomenon. In her classic Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory, the critic Marjorie Hope Nicolson shows that before Petrarch, mountains were generally considered signs of God’s wrath, imperfections visited upon the otherwise even countenance of the earth.

We think of mountains as primary sites of the sublime: awful in the sense of inspiring awe. They used to be encountered as merely forbidding: awful in the sense of being something fearsome and terrible.

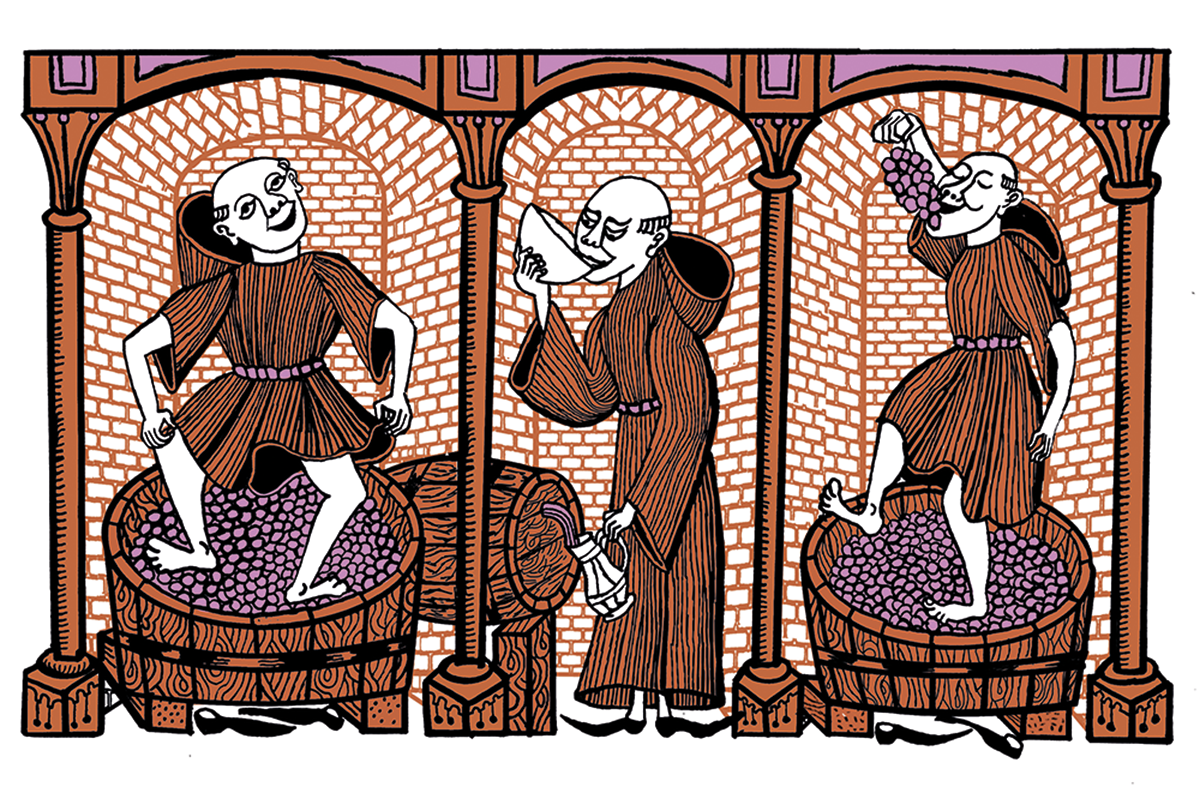

Fortunately for us wine drinkers, the Benedictine monks who have been planting grapes on the slopes of Mount Ventoux for centuries were not sissies. Their current endeavors, a collaboration between the monks and the Beaumont du Ventoux Winery has yielded some excellent wine. I recently tasted the 2020 Via Caritatis “Vox Angelorum” Ventoux Rouge. It’s a Rhône wine, but with the traditional cépage reversed. Instead of being predominantly Grenache, it is 70 percent Syrah and 30 percent Grenache.

The appellation Ventoux AOC was known as Côtes de Ventoux until 2009. It is located twenty-five miles northeast of Avignon, in the Vaucluse department. The terraced vineyards of Via Caritatis (“charity”) are planted about 1,100 to 1,300 feet above sea level. The sunny Mediterranean climate provides plenty of warmth but the area is cooled by the northwesterly Mistral winds.

The resulting wine is a limpid, aromatic, and berry-bright, lighter, more inveigling, less dusty than your typical Rhône wine, full of surprising subtleties and unexpected, swirling depths. Hints of anise and a variety of dark fruits embroider the taste. If you close your eyes and listen carefully you may just hear the “voice of angels” to which its name alludes. Your pocketbook, too, will be happy, since the wine will only set you back about $20.

I think that Carneros in the Napa Valley may be about as far from Mount Ventoux as it is possible for a vineyard to get. But I am pleased to be able to tell you about a spectacular new-to-me find: Truchard Vineyards, 400 contiguous, well-drained acres nestled into the fog-cooled hills and dales abutting the foothills of what becomes the Mayacamas mountain range. The vineyard is home to several soil types — clay, shale, sandstone, lava rock, and volcanic ash — and a dozen grape varieties, including Syrah, Roussanne, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Pinot Noir, Merlot and Zinfandel.

The Truchards, Tony and Jo Ann, have been growing grapes in Carneros (Spanish for “rams,” which used to roam there) since 1974. At first, they sold their produce to various premier wineries in Napa and Sonoma. In 1989, they began making their own wine. It was an instant success.

I don’t know how I managed to miss it all these years, but it was only recently that I became Truchard-conscious. A friend introduced me to their estate-bottled 2022 Pinot Noir. Delicious! The wine is produced from mature vines of twenty-six to nearly fifty years old and is meticulously organized (if a wine can said to be organized) from carefully curated clones from several French and California Pinot stocks.

The result is an eminently approachable but seductively complex wine, robust and self-sufficient but with no harsh tannic notes. It was only $33 at my local wine shop, a serious bargain.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply